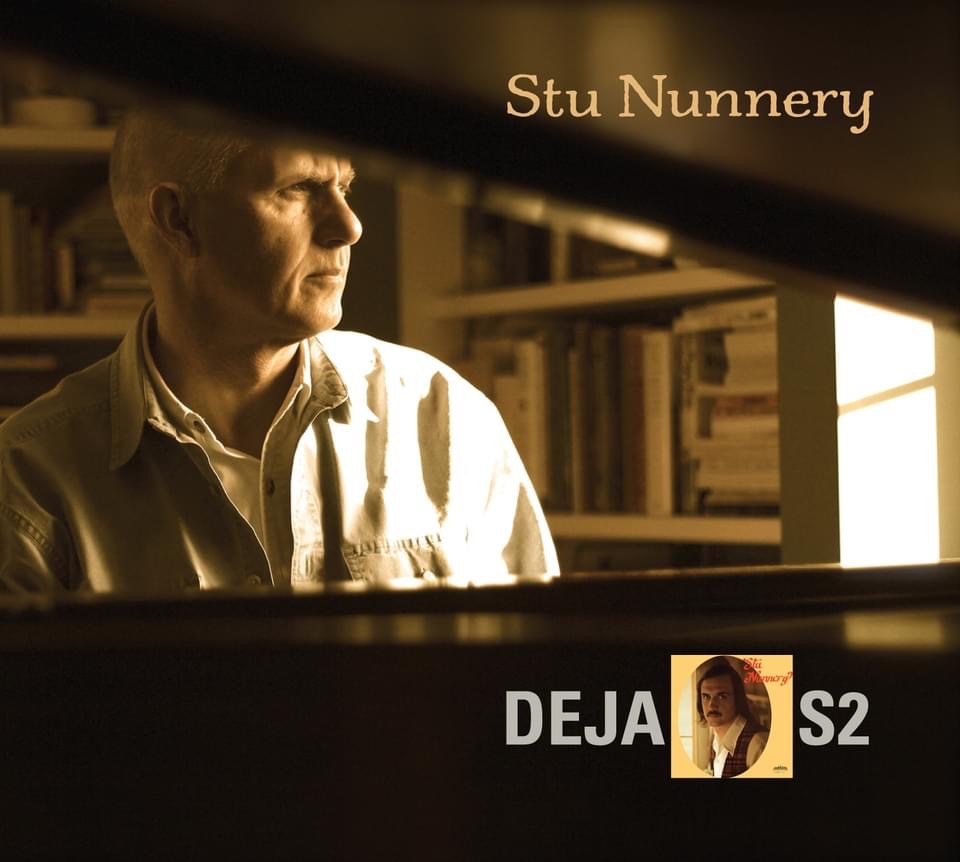

A Life In and Out of Music

Editor’s Note:

Stu Nunnery is a late deafened musician who had to leave music, and now, after much hard work, is back. He wrote an article in a special issue of Hearing Review in 2018 when I was a guest editor. This article—well worth reading—can be found at https://hearingreview.com/hearing-loss/hearing-loss-prevention/music-entertainment/rebuilding-musical-self. In fact, the entire October 2018 issue of HearingReview.com is well worth reading. Its all about extending one’s musical career.

What happened to music when I “lost my hearing?”

Current estimates say that fifty million Americans have some kind of hearing loss. The causes are many: genetics, aging, noise, medications, infection, and other health conditions. Every hearing loss is different. That every hearing loss varies in intensity and severity. That every hearing loss affects every individual in its own unique way.

Among this group are musicians who endure a special kind of hell depending on their circumstances, talents, and profession position (See “Huey Lewis.”). The best guess says that some 30–40% of rock musicians suffer from hearing loss, while classical musicians suffer at a higher rate - some 50–60%. A musician’s hearing loss might just affect volume and his or her ability to hear themselves or their instrument loud enough. But it also might affect pitch and create tonal distortion making it difficult for them to tune their instrument or play and sing in key. It might be a combination of things that impact the musician only slightly - or enough to end a career. Being a creative lot, some musicians try to compensate for their hearing loss through technology, advances in hearing aids, and their own bag of tricks. Some, of course, have no options at all.

That was me.

Note: It is here where my larger story veers off into new territory and covers years and events that many, if not most of my friends and fans, know little about.

In my case, and, in the course of a year, my life in music ended, started briefly, then ended again - this time for good. In 1982, after my last recording sessions in New York left me without a path forward, I disappeared.

Just disappeared.

I stopped looking for another record deal, no longer took bookings for jingle jobs from the talent service, and didn’t call friends or colleagues to tell them what had happened and that I wouldn’t be coming back. I was too distressed, too embarrassed. At that time in my life and profession, I had never heard of a musician losing their hearing, so there was no reference point other than me. It must be my fault, I believed. Few of my colleagues in the music business contacted me to find out what had happened though I don’t fault them for that. I’d be lying, however, if I didn’t admit that I was hurt enough to think that maybe I wasn’t the “hot stuff” that I thought I was.

Or something.

So, what happened to music when I “lost my hearing?”

Music became just another source of noise. I still had some hearing in my right, which was eventually fixed with a hearing aid. Overall, however, the sensori-neural damage to my ears interfered with speech comprehension and music. My hearing for speech was relatively functional and I could hear voices, but there would always be frequency gaps that left holes in what I could hear cleanly. Oddly, my hearing loss affected the lower frequencies/rather then than midrange or higher frequencies which is more common. To this day, I have trouble hearing deep voices and thunder among other things. Meanwhile, the hissing and roaring of tinnitus from the left ear became a lifetime annoyance and distraction.

From the beginning, the music that I tried to listen to wasn’t pretty or moving. It wasn’t inspiring or soothing, exciting or hot. It wasn’t hand clapping, toe tapping good. More often than not, it was loud and physically painful to listen to.

I couldn’t sing along with melodies because I couldn’t understand or decipher them. I couldn’t guess what band or artist or whose music was playing. I couldn’t pick out an instrument or a voice, or the key in which a song was being played. I couldn’t hear the lyrics because they were buried in the noise or identify a song in the first couple of notes, and often, not at all. When I sat at the piano and played middle C on the keyboard, I heard a mess of notes, tones or rings and couldn’t find middle C with my ear. You may know that there are eight Cs on the keyboard, and they should all sound the same just an octave higher/lower. To me, they were all different notes. A mess of notes.

I couldn’t sit at the piano and play a song that I knew or had written and be able to sing along because I would be singing out of key. I could see the note I was playing, but I couldn’t repeat it vocally. Music was distorted and my sense of it was even further distorted. The only music that I could make some sense of was music that I knew from my past, that I could tell from the title, and/or that my music and muscle memories could call up.

Even today, some forty years later, I cannot enjoy songs that I do not know, so I cannot learn a new song without reading a chart and I don’t do that very well. In effect, music stopped for me about 1983. Any music produced after that, any artist or band that first appeared then is foreign to me. After years of trying to get my hearing back into to some semblance of order, there is still damage to my musical hearing that can’t be fixed.

So, just as the music did, I disappeared.

From the time I was a teenager playing piano and guitar in school and talent shows and hootnannies and churches and choirs, to clubs, restaurants and bars, and later to stages and the recording studios, making music, writing and performing my own songs was the persistent dream of my adult life. Suddenly, after enjoying some success and long before I ever thought it would, that dream was gone.

Who was I then, and what kind of a life was I to have without music?

In my early 20s, I wrote a song called “In the Eyes of the Forgotten Man.” I don’t know where it came from - not yet having lived a life filled with regrets, but there it was. I recorded a demo with my musical friend Wayne Wadhams at his studio in Boston in 1974-75. The recording is quite raw, not fit for release without touch ups or another go around, but it’s part of my early music-making process that most musicians go through in writing and recording songs. I thought you might find it interesting. In addition, I think many of us can identify with the lyrics – about dreams that die hard. It was one of the songs on the demo that resulted in a recording contract with Epic Records in 1976. I think this may be an appropriate spot to drop it into the story.

“In the Eyes of the Forgotten Man”

Written by Stu Nunnery

c. 1975 Busker Songs

Recorded at Studio B, Boston, MA

Producers: Wayne Wadhams and Stu Nunnery

Engineer Allen D. Smith

Musicians: Stu Nunnery, piano; Bob Klein, drums; Jack Kivolowitz/Doug Ferrara, bass, guitars

Vocals: Stu Nunnery

But then things started to go south with my hearing. Just click on this link to HearingReview.com and you will read about my rebuilding of my musical self… not quite bionic, but that was part of it; the rest was my brain.