To the Brain and Back: “Second-Person Neuroscience” For Hearing Loss, Aging, and Social Connection

A sense of connection is the foundation of social engagement and the development of personal relationships. For many, this comes in the form of spoken communication. People living with hearing loss, however, feel less socially connected because speech and language are more difficult for them to perceive in conversation or group settings. Such effects are exacerbated in noisy environments, which are unfortunately common at social gatherings. Unsurprisingly, research studies repeatedly show an increased risk of social isolation and loneliness in people with hearing loss.1 Audiologists play an important role in addressing these social needs through hearing healthcare, for instance, by providing hearing aids that make speech and language easier to perceive. Indeed, people are more satisfied with their hearing aids when they feel higher levels of social support.2

Many people with properly fitted hearing aids nonetheless have difficulty recovering a sense of social connection.2 The available research that could provide insight into this problem is limited because most studies use methodologies that are divorced from real social contexts. For example, speech-in-noise listening is an important skill for spoken communication and a target of aural rehabilitation. Still, standard tests used in research (e.g., QuickSIN and HINT) require patients to listen, remember, and repeat entire sentences verbatim from a pre-recorded playlist while sitting alone in sound booths.3,4 In daily life, however, it is rare to replicate the speech of another person while isolated from them. Listening and communicating in the real world are embedded in an active social context in which conversation partners can influence one another, see each other’s perspectives, and collectively pursue complex goals. If this missing context was included in research designs, we may find clearer links between aspects of speech and language perception and the social needs of hearing aid users and people with hearing loss.

Here, we introduce a disciplinary framework, second-person neuroscience – brain and behaviour research involving two or more interacting individuals – that seeks to capture these critical social elements in a research setting. We describe how second-person research can help us understand the relationships among hearing loss, hearing aid use, speech perception, and social connection. These factors are highly relevant to the older adult community, and we emphasize research in this population.

Second-Person Neuroscience

Second-person neuroscience investigates the social basis of the brain through research designs involving two or more interacting people. This methodological framework evolved from the field of social neuroscience in response to criticisms of previous research that placed participants in isolation when measuring their social perceptions. We now know that social cognition and the factors that influence it depend on real-time interactions between two or more people (or at least the perception of an authentic interaction with a real person), which cannot be inferred from observing a social stimulus in isolation from others.5 We share three example concepts of second-person neuroscience that are relevant for understanding social connection that results from face-to-face spoken conversations.6

1. Mutual influence

During social interactions, people direct their actions toward their partners and can influence them. People also know that their partner’s actions exert influence in turn. During a face-to-face conversation, for example, the words one person uses naturally determine what the other person understands, and therefore what they say in response. Conversation partners can adjust how and what they say to influence the other person’s perception, such as speaking more slowly, louder, or more predictably in background noise to help their partner hear the speech.

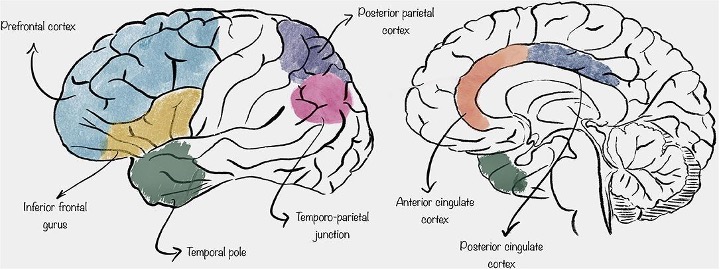

A neuroscience example of mutual influence comes from comparing brain activity in people who passively observe a social interaction (such as a video) to when they participate in a real social interaction 7. In a real interaction, a brain network known as the mentalizing network engaged, which involves regions such as the prefrontal cortex, anterior temporal lobes, inferior frontal gyrus, temporoparietal junction, and the cingulate cortex (Figure 1). These areas support mentalizing, which is the process of inferring the mental states (beliefs, intentions, knowledge) of others while being aware that others are doing the same to us. In other words, the mentalizing network helps us understand what others are thinking. Therefore, the mentalizing network is the “brain context” in which speech and language perception occur during a face-to-face conversation between two or more people.

2. Behavioural coordination.

During social interaction, people often cooperate to address collective challenges by coordinating their actions or language. Imitation is also important, as individuals naturally mirror others’ facial expressions, gestures, word choices, and grammatical structures during conversation. An interesting type of behavioural coordination occurs when interacting partners align their body movements and their underlying physiology in a rhythmic, time-locked fashion. This is a relational phenomenon known as interpersonal synchrony. When the brain activity of two interacting partners is recorded in tandem, fluctuations of electrical and metabolic activity synchronize in time.6 Interacting partners also show synchrony in heart rate and autonomic nervous system activity,7,8 suggesting that they become temporarily aligned in bodily regulation. Moreover, synchronous behaviours modulate cognition, emotion, motivation, and pain perception, which explains findings such as enhanced positive mood, elevated pain thresholds during group movement, and changes in attention and memory for socially relevant information.9 Crucially, interpersonal synchrony is also linked to increased feelings of social connection.10

3. Shared goals & representations

During social interaction, people often see and respond to the same events and therefore share the same perceptual experiences. With conversation, people also use language to help the other person understand their perspective, identify similar goals, and find overall “common ground.” Second-person neuroscience attempts to identify the underlying neural representations (patterns of brain activity that reflect perception of objects or knowledge-based concepts held in memory) that are similar between interacting partners. For example, there is greater neural similarity between people when they share emotions or have the same interpretation of an event.11,12 When speech is difficult to understand, it may be harder to establish shared representations, which could reduce a sense of social connection.

Second-Person Research in Aging and Hearing Loss

Second-person research in aging and hearing loss is still in its infancy and has mainly relied on behavioural rather than brain-based methods. Most research pairs older adults with varying levels of hearing loss into dyads (two-person groups) or multi-person groups such as triads or quartets, and asks them to perform interactive, conversational tasks that are naturalistic and resemble real-life situations. Some studies ask participants to discuss film preferences, make judgments on “close-call” incidents, and resolve various ethical dilemmas.13 Many studies are completed in the presence of background noise, which strains speech perception and information transfer between partners. Other researchers use cooperative activities, such as the Diapix (spot-the-difference) task, in which participants are given a set of nearly identical images and asked to verbally communicate to find 10–12 differences between picture pairs.14 These methods span the main features of social interaction including mutual influence (“What I say matters to you.”), coordinated behaviour (“Let’s work together to solve this.”), and shared representations (“We see the same thing on our image card.”). See Figure 2 for an example comparison between a single-person and a second-person research setup.

This work has yielded several important findings. Normal-hearing older adults use a variety of intelligibility-optimizing behaviours when conversing in noisy environments.15 They speak louder, slower, and reduce the time they are talking during their turn. They direct their gaze to the speaker’s mouth to use visual speech cues and lean toward their partner to hear them better.13,16 They were also found to move and sway their heads and bodies in time together, an example of interpersonal synchrony.7 Older adults, therefore, use very active, embodied strategies to reduce effort, increase predictability, and facilitate information transfer when they must listen and converse in noise. These aspects cannot be accounted for when testing their speech-in-noise perception when alone in a sound booth.

When one or more partners has hearing loss, conversation requires more effort and coordination between talkers is reduced.17–19 Turn taking is more erratic, there is less synchrony, and there are longer pauses between utterances. Outside observers describe conversations involving people with hearing loss as “harder to follow” and with “less flow.” One study found that the significant other of a person with hearing loss takes on a “leading role” more frequently during interactions, suggesting a reliance on the conversation partner who can provide a predictable structure.20 These findings overall suggest that hearing loss makes conversing in noise more cognitively demanding, and it is harder to establish or maintain coordination and synchrony with a partner unless they provide familiar or more certain communication cues. Importantly, studies also show that hearing aid use can improve these outcomes.17

These initial findings set the stage for future research with neuroimaging techniques such as EEG and fNIRS, aligned with second-person neuroscience framework. Hyperscanning is the collection of brain activity from more than one person simultaneously. It can potentially show how hearing loss affects inter-brain synchrony and the emergence of shared neural representations during conversation, as well as how background noise affects them. Understanding the effects of hearing loss on activation of the mentalizing network will also be a major objective, which may help predict feelings of social disconnection.

Challenges and Applications for Research and Audiology

Although second-person research is ripe with opportunity in hearing and communication science, it is not easy. Such studies are logistically difficult to execute; recruiting, scheduling, and coordinating participants in dyads or groups can be challenging. It is also difficult to balance the uncertainty of natural conversation with experimental rigor, and often lots of data needs to be collected to detect statistical effects. Interpersonal factors such as relational closeness and familiarity, prior biases, personality traits, mixtures of gender or ethnic backgrounds, and different conversational styles introduce variability in this line of research that is difficult to standardize or account for.20

Audiologists and hearing researchers have much to gain if these challenges are met. For instance, knowledge about how people with hearing loss dynamically adapt to social interactions can predict their satisfaction with hearing devices.2,21 Rehabilitation that focuses on elements of social connection, such as behavioural coordination and establishment of shared representations, may confer benefits beyond speech perception training alone. Reciprocally, the social contacts of people with hearing loss may also benefit from knowing how to increase social inclusion through intelligibility-optimizing strategies, such as deliberate turn-taking and the adoption of predictable, accommodating speech patterns. These efforts may maximize the outcomes of hearing healthcare.

References

- Shukla, A., Harper, M., Pedersen, E., Goman, A., Suen, J. J., Price, C., ... & Reed, N. S. (2020). Hearing loss, loneliness, and social isolation: a systematic review. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 162(5), 622-633.

- Singh, G., Lau, S. T., & Pichora-Fuller, M. K. (2015). Social support predicts hearing aid satisfaction. Ear and Hearing, 36(6), 664-676.

- Füllgrabe, C., & Rosen, S. (2016). On The (Un)importance of Working Memory in Speech-inNoise Processing for Listeners with Normal Hearing Thresholds. Frontiers in psychology, 7, 1268. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01268

- Gordon-Salant, S., & Cole, S. S. (2016). Effects of Age and Working Memory Capacity on Speech Recognition Performance in Noise Among Listeners With Normal Hearing. Ear and hearing, 37(5), 593–602. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000316

- Schilbach, L., Timmermans, B., Reddy, V., Costall, A., Bente, G., Schlicht, T., & Vogeley, K. (2013). Toward a second-person neuroscience1. Behavioral and brain sciences, 36(4), 393-414.

- Redcay, E., & Schilbach, L. (2019). Using second-person neuroscience to elucidate the mechanisms of social interaction. Nature reviews neuroscience, 20(8), 495-505.

- Monticelli M, Zeppa P, Mammi M, Penner F, Melcarne A, Zenga F and Garbossa D (2021) Where We Mentalize: Main Cortical Areas Involved in Mentalization. Front. Neurol. 12:712532. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.712532. Shared under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY).

- Gordon, I., Gilboa, A., Cohen, S., Milstein, N., Haimovich, N., Pinhasi, S., & Siegman, S. (2020). Physiological and behavioral synchrony predict group cohesion and performance. Scientific Reports, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65670-1

- Tarr, B., Launay, J., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2016). Silent Disco: Dancing in synchrony leads to elevated pain thresholds and Social Closeness. Evolution and Human Behavior, 37(5), 343–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2016.02.004

- Cirelli, L. K. (2018). How interpersonal synchrony facilitates early prosocial behavior. Current opinion in psychology, 20, 35-39

- Nummenmaa, L., Glerean, E., Viinikainen, M., Jääskeläinen, I. P., Hari, R., & Sams, M. (2012). Emotions promote social interaction by synchronizing brain activity across individuals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(24), 9599-9604.

- Yeshurun, Y., Swanson, S., Simony, E., Chen, J., Lazaridi, C., Honey, C. J., & Hasson, U. (2017). Same story, different story: the neural representation of interpretive frameworks. Psychological science, 28(3), 307-319.

- Hadley, L. V., Brimijoin, W. O., & Whitmer, W. M. (2019). Speech, movement, and gaze behaviours during dyadic conversation in noise. Scientific Reports, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46416-0

- McInerney, M., & Walden, P. (2013). Evaluating the use of an assistive listening device for communication efficiency using the Diapix Task: A pilot study. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica, 65(1), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1159/000350490

- Hadley, L. V., & Ward, J. A. (2021). Synchrony as a measure of conversation difficulty: Movement coherence increases with background noise level and complexity in dyads and triads. PLoS ONE, 16(10), e0258247. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258247.

- Hadley, L. V., Fisher, N. K., & Pickering, M. J. (2020). Listeners are better at predicting speakers similar to themselves. Acta Psychologica, 208, 103094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2020.103094.

- Petersen, E. B., MacDonald, E. N., & Sørensen, A. J. M. (2022). The effects of hearing-aid amplification and noise on conversational dynamics between normal-hearing and hearing-impaired talkers. Trends in Hearing, 26, 23312165221103340. https://doi.org/10.1177/23312165221103340.

- Sørensen, A. J. M., Lunner, T., & MacDonald, E. N. (2024). Conversational dynamics in task dialogue between interlocutors with and without hearing impairment. Trends in Hearing, 28. https://doi.org/10.1177/23312165241296073.

- Petersen, E. B. (2025). Hearing-loss related variations in turn-taking time affect how conversations are perceived. PLOS ONE, 20(6), e0325244. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0325244.

- Tschacher, W., Rees, G. M., & Ramseyer, F. (2014). Nonverbal synchrony and affect in dyadic interactions. Frontiers in Psychology, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01323

- Vogelzang, M., Thiel, C. M., Rosemann, S., Rieger, J. W., & Ruigendijk, E. (2021). Effects of age-related hearing loss and hearing aid experience on sentence processing. Scientific Reports, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-85349-5