Beyond Amplification: A Comprehensive, Evidence-Based Approach to Tinnitus Management

Tinnitus is the perception of sound without an external source, often described as ringing, buzzing, or hissing.1–3 This article focuses on subjective chronic tinnitus, the most common type, typically associated with hearing loss without an identifiable medical condition.1,4,5 Although its definition seems straightforward, tinnitus is a complex and heterogeneous symptom, linked to a range of health conditions and capable of significantly affecting quality of life.1,6 Effective management requires addressing not only the disruptive symptom but also the broader context of each patient’s experience, including hearing and medical history, coping strategies, and overall well-being. Despite this complexity, many patients still receive only hearing aids or, in some cases, a referral to an audiologist trained in Tinnitus Retraining Therapy (TRT), Progressive Tinnitus Management (PTM), or to a therapist specializing in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). While these treatment modalities can provide clinically significant relief, access remains limited, with relatively few certified clinicians and limited virtual options.7,8 Yet the current situation falls short in addressing Canadians’ needs, particularly as recent evidence shows tinnitus is more prevalent than previously estimated. The 2019 epidemiological study Tinnitus in Canada reported high prevalence across all age groups.9

Evidence from the 2016 randomized clinical trial, Effect of Tinnitus Retraining Therapy vs Standard of Care on Tinnitus-Related Quality of Life, further illustrates the challenges in treatment. Participants receiving full TRT (counselling + sound generators), partial TRT (counselling + placebo devices), or standard care (counselling + encouragement of environmental sound enrichment) all improved significantly, with no single approach proving superior.10 These findings indicate that counselling and sound enrichment strategies are central to intervention’s effectiveness, supporting the use of a comprehensive, patient-focused approach to tinnitus care.

Audiologists’ expertise in patient- and family-centered care, developed through the management of hearing loss, is directly applicable to supporting patients with bothersome tinnitus.11 Assessment begins with a detailed case history to understand the nature and impact of tinnitus and identify contributing factors, such as noise exposure, reliance on maladaptive coping behaviours, lifestyle habits, and overall well-being. Standardized tools such as the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI), Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI), and Tinnitus and Hearing Survey (THS) help assess severity, differentiate tinnitus related challenges from hearing loss, and track outcomes.12-14 Quick measures, such as Visual Analog Scales (VAS), provide an efficient snapshot of tinnitus loudness and intrusiveness when time is limited.15 Psychometric questionnaires including the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), also enable clinicians to screen for comorbid emotional disturbances.16 Because hearing loss is a major risk factor for both the onset and worsening of tinnitus, a comprehensive audiological evaluation is essential.3,17 Understanding the degree and nature of hearing loss, its impact on speech perception in noise, and associated conditions such as hyperacusis allows clinicians to provide effective interventions.

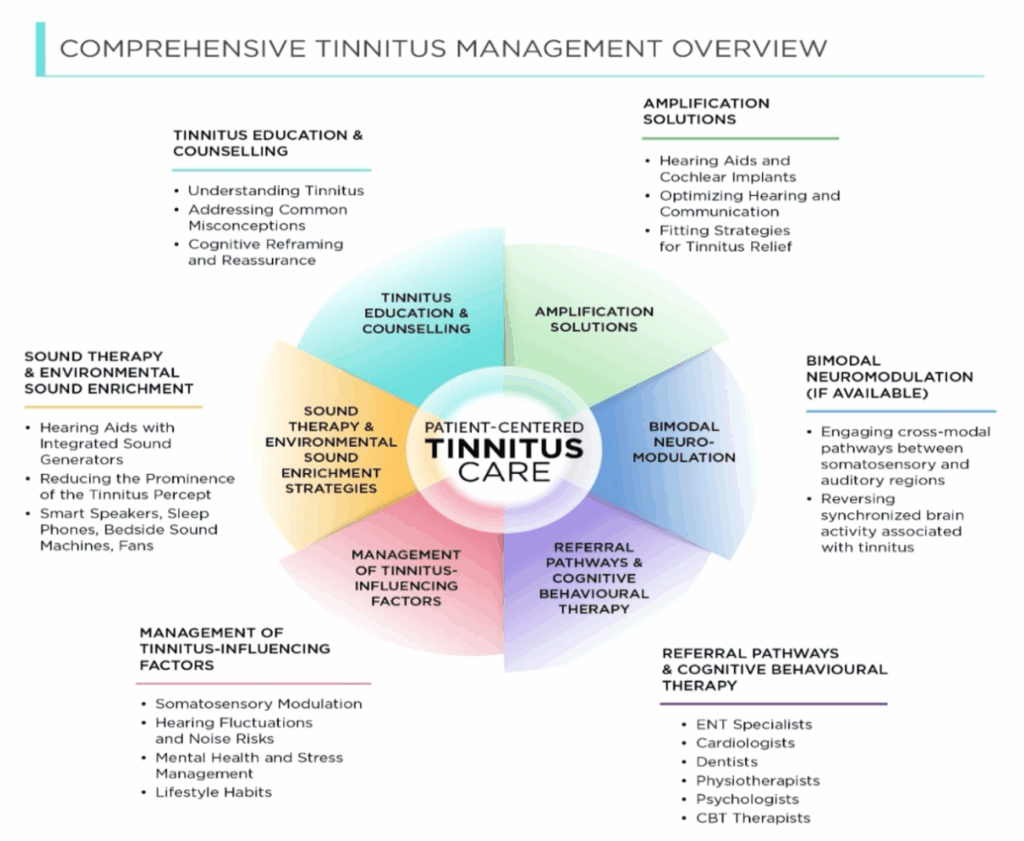

In this article, I describe how audiologists can implement an evidence-based approach to tinnitus management, incorporating tinnitus education and counselling, amplification solutions, sound therapy and environmental sound enrichment strategies, bimodal neuromodulation treatment (if available), ongoing management of tinnitus-influencing factors, and timely referrals to medical specialists and mental health professionals trained in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy.3,4,5,18,19

Tinnitus Education and Counselling

Audiology-based counselling, also known as educational or informational counselling (IC), is a cornerstone of effective tinnitus management, helping patients understand their condition and develop strategies to cope with its impact.3,18–20 Patients often arrive with worry, uncertainty, or fear that their tinnitus will worsen over time, that they will lose their hearing, or that they will not be able to cope.21 Some have been told by healthcare professionals or others, including online sources, that nothing can be done.22 While there is currently no medical cure, it is important to reassure patients that effective interventions exist to reduce its impact and improve quality of life.

Audiologists play a key role in educating patients about tinnitus by clarifying what it is (i.e., a prevalent symptom rather than a disease), identifying its nature (i.e., subjective vs. objective), and associated conditions (e.g., hearing loss, decreased sound tolerance, stress), while addressing common misconceptions such as the belief that it typically signals a brain tumor (rarely) or directly causes hearing loss or hearing difficulties.4,19,20,23 By reframing tinnitus as a manageable condition rather than a threatening one, clinicians can help patients build coping skills and improve their overall well-being. Cognitive reframing has emerged as a pivotal counselling strategy, assisting patients in regaining and consolidating a sense of control while lessening the psychological burden often associated with chronic tinnitus.19,23,24

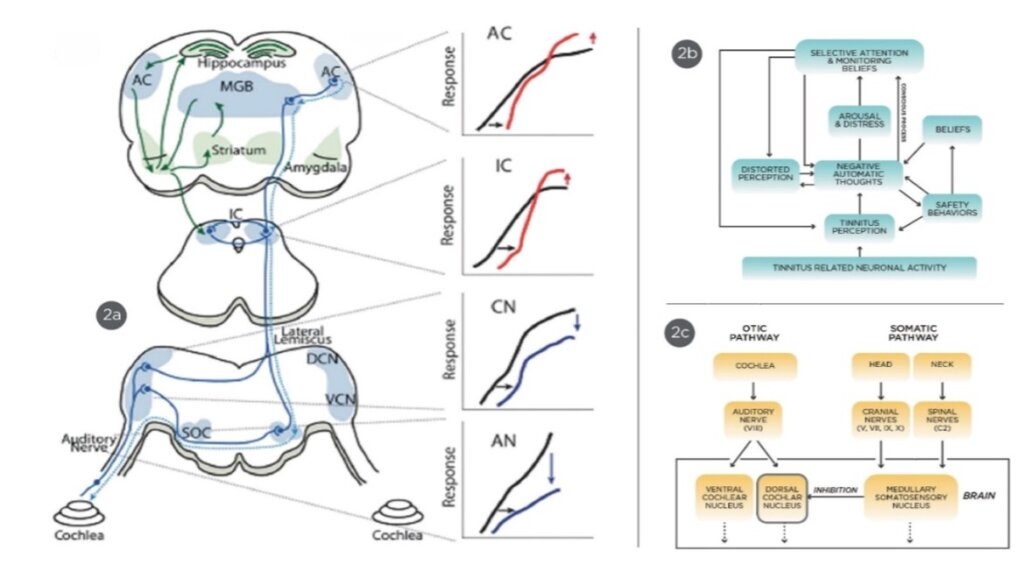

Helping patients recognize that tinnitus is influenced by multiple, often manageable factors such as hearing loss, stress, sleep disturbances, and overall health (e.g., blood pressure, diabetes, and mental well-being) further normalizes the symptom and reduces distress or confusion. This knowledge provides a foundation for discussing individualized strategies, including amplification, sound enrichment, stress management, all of which support long term adjustment and coping. Subjective tinnitus reflects a brain response driven by maladaptive neural mechanisms that influence its onset, fluctuation, and persistence. Theoretical models provide a structured framework for explaining these processes.25–27 The central gain model describes how hearing loss can increase neural sensitivity and spontaneous neural activity, contributing to tinnitus perception.24 The cognitive-behavioral model emphasizes the role of negative thoughts, maladaptive or safety-seeking behaviours, stress, and insomnia in exacerbating tinnitus perception and influencing its emotional impact.25 The somatosensory modulation model explains how input from the somatosensory or musculoskeletal systems, such as the neck, head, or jaw, can modulate tinnitus perception.26 In clinical practice, however, more than one model may be needed to account for the complexity of an individual’s tinnitus. Together, these models allow clinicians to explain the multifactorial nature of tinnitus and guide individualized management strategies.

This illustration presents three conceptual frameworks: the Central Gain Model (2a), showing how reduced auditory input can enhance neural activity along the auditory pathway; the Cognitive-Behavioral Model (2b), depicting how negative thoughts, attention, and emotional responses interact to influence tinnitus perception; and the Somatosensory Modulation Model (2c), highlighting how non-auditory inputs from the somatosensory system can alter auditory processing and tinnitus perception.

The iceberg model offers a simple yet powerful way to explain why some patients find tinnitus more bothersome than others.3,28 Above the surface lies the tinnitus percept itself, along with the experience of hearing difficulty and reduced sound tolerance. Beneath the surface are a range of contributing factors such as unhelpful thinking styles (e.g., catastrophizing tinnitus symptoms, ruminating about its causes), safety seeking behaviours (i.e., constant monitoring of tinnitus levels, excessive reliance on earplugs or headphones, avoidance of social settings for fear of aggravating symptoms), stress, anxiety, depression, poor sleep, and diminished overall well-being, all of which can amplify the severity of tinnitus. The iceberg metaphor helps patients connect the dots quickly, showing that their reaction to tinnitus is shaped not only by the sound they perceive, but also by underlying emotional and health-related influences. It also illustrates the bidirectional association, whereby tinnitus can worsen mental health concerns, and in turn, these concerns can heighten the perception and distress of tinnitus.4,29,30

Developed by Dany Pineault, Au.D., this model shows that the auditory aspects of tinnitus (ringing, hearing difficulty, reduced sound tolerance) are only the visible portion, while psychological and emotional factors (stress, anxiety, depression, sleep disturbances) lie beneath the surface.

Evidence supports the value of counselling alone in reducing tinnitus distress. In a longitudinal cohort study, Liu et al. (2018) provided informational counselling (IC) to 159 adults with chronic primary tinnitus, addressing its nature, causes, misconceptions, and individualized coping strategies.20 Participants had varying audiometric profiles, and no hearing aids or sound generators were used. Following counselling, mean THI scores decreased from 46.1 to 31.9 within 1 to 3 months, with 60% of participants achieving a reduction of at least 7 points, a widely recognized minimal clinically important difference (MCID), indicating meaningful improvement in tinnitus-related quality of life and sleep quality.20

For audiologists wishing to expand their foundational knowledge in tinnitus, numerous courses and professional podcasts are available. For example, the Pacific Audiology Group and Widex Canada podcasts offer free courses on tinnitus assessment and management strategies.31,32

Amplification Solutions

Amplification plays a central role in managing tinnitus for patients with hearing loss.4,33–36 Several mechanisms may explain its benefits. By improving auditory input, amplification can alleviate stress associated with communication difficulties, which may otherwise exacerbate tinnitus perception.25,33,36 It can also partially mask the tinnitus percept by directing attention to external sounds, making the internal perception less prominent.34 Moreover, stimulation of deprived auditory pathways may promote adaptive plasticity, cortical reorganization, and normalization of central gain, potentially reversing maladaptive neural changes caused by chronic hearing loss.34–37 Together, these mechanisms provide both perceptual and emotional relief, demonstrating the therapeutic value of amplification in tinnitus management. It's worth noting that these positive outcomes extend beyond traditional hearing aids and include extended-wear options, cochlear implants, and bone conduction hearing devices.38,39

Although informational counselling (IC) can be helpful on its own, evidence from patients with mild hearing loss indicates that adding amplification may provide even greater benefit. In a randomized controlled trial by Kam et al. (2024), 38 adults with mild hearing loss were assigned to one of three treatments: informational counselling (IC) alone; IC plus hearing aid amplification; or IC plus individualized music sound therapy.40 Over 12 months, the group receiving amplification plus IC experienced a mean reduction in Tinnitus Functional Index (Chinese version, TFI-CH) of about 20.6 points (from ~55.5 to ~34.9). On the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI-CH), the HA + IC group improved by about 16.3 points compared to ~7.3 points in the IC-only group. These reductions in both TFI-CH and THI-CH scores exceeded the MCID, representing clinically meaningful improvement.

Hearing aid selection should reflect the patient’s audiometric profile. Open-fit devices are best for high-frequency loss with normal low frequencies, while custom molds suit low-frequency loss by providing adequate gain without feedback. Amplification is most effective when the tinnitus pitch falls within the aid’s audible bandwidth, which can be estimated through pitch and loudness matching.41,42 Tinnitus pitch often corresponds to the region of hearing loss—for example, high-frequency loss typically aligns with high-pitched tinnitus.41 Clinicians may also need to adjust features such as expansion, directional microphones, or noise reduction to optimize background noise amplification for masking, while avoiding reduced hearing ability or aggravation of hyperacusis.4

Key prescriptive considerations:

- Maximizing audibility while maintaining safe output levels.

- Amplifying low-level sounds in tinnitus-affected frequencies.

- Preserving background noise to leverage partial masking effects.

- Verifying fittings with real-ear measurements to ensure optimal benefit.

Sound Therapy and Environmental Sound Enrichment Strategies

Sound therapy and sound enrichment can be valuable tools for patients with tinnitus, particularly when combined with tinnitus education and counselling.43 Although the exact neural mechanisms are still under investigation, gradual exposure to low-level therapeutic sound may help recalibrate the auditory brain circuits, reducing excessive central gain, which can decrease the prominence of tinnitus and support adaptive neural changes. The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation classifies sound therapy as an “optional” recommendation due to limited high-quality evidence.4 However, research from the National Center for Rehabilitative Auditory Research (NCRAR) and clinical experience suggest many patients benefit from it.44– 46 Indeed, sound therapy can validate the experience of tinnitus, provide relief and distraction, foster a sense of control, reduce distress, and support overall well-being.47 Many sound therapy studies are considered “low quality” in systematic reviews, mainly because blinding participants is difficult in behavioral or device-based interventions.48 Blinding helps control for placebo effects, but in treatments like sound therapy or CBT, participants are aware of the intervention, making full blinding challenging. Despite this, unblinded studies of behavioral treatments, such as CBT for tinnitus, demonstrate meaningful patient benefits, supporting the idea that sound therapy can also be effective even when full blinding is not feasible.49

Hearing aids with integrated sound generators are suitable for patients with hearing loss, sub-clinical or normal hearing, or single-sided deafness (fitting the unaffected ear can still target central auditory pathways). Device selection depends on the audiometric profile, degree of hearing loss, and any physical or medical considerations. Effective sound therapy requires a sufficiently wide frequency range to mask or blend the tinnitus, using sounds such as broadband or narrowband noise, fractal-based tones, frequency-matched shaped noise, or nature sounds. The sound should be pleasant and emotionally neutral, with the patient actively involved in selecting a sound they find comfortable and enjoyable.

Fitting strategies play a critical role in treatment outcomes. Audiologists should clearly explain the available approaches and their potential effects. Total masking fully covers tinnitus and can provide immediate relief, but it may impede long-term habituation or, in some cases, exacerbate symptoms. Partial masking, or the 'mixing point' approach, blends the therapeutic sound with the tinnitus, keeping it perceptible to support gradual habituation. While partial masking is preferred, total masking may be warranted in select cases—such as catastrophic tinnitus or severe musical and auditory verbal hallucinations.50

In addition to ear-level devices designed specifically for sound therapy (e.g., hearing aids with integrated sound generators), patients can also benefit from environmental sound enrichment strategies in everyday settings when not using their hearing aids. These strategies use sounds from devices or other technology to reduce the prominence of tinnitus, helping patients manage their reactions at home, at work, and in daily life. Patients should be encouraged to select sounds they find soothing and nonintrusive, such as white or pink noise, the hum of a fan, gentle rainfall, ocean waves, or soft instrumental music, to support relaxation and reduce the perceived salience of tinnitus. These strategies can benefit patients with tinnitus ranging from mild annoyance to more disruptive or bothersome experiences. Consumer sound-generating devices—including smart speakers, wearable options (e.g., SleepPhones), pillow speakers, and bedside nature sound machines or fans—are particularly useful in quiet environments, such as the bedroom at night, when tinnitus is often most noticeable.51 Evidence suggests that sound enrichment contributes to decreased tinnitus awareness and improved sleep outcomes in clinical populations.52

Bimodal Neuromodulation (If Available)

Bimodal neuromodulation is a validated approach for alleviating tinnitus symptoms, combining auditory stimulation with a secondary somatosensory input—typically via the tongue, hand, or ear—to modulate neural activity associated with tinnitus perception. This approach builds on the way somatosensory signals can influence the brain’s auditory circuits, particularly within the dorsal cochlear nucleus, making it possible to pair sound with targeted stimulation.53

In a randomized clinical trial by Jones et al. (2023), precisely timed bisensory stimulation (headphones paired with gentle electrical stimulation applied to the face or upper neck) was shown to reverse synchronized brain circuits associated with tinnitus.54 Participants receiving active treatment experienced significant reductions in tinnitus loudness and distress, reflected in clinically meaningful improvements on both the Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI) and the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) that exceeded the MCID, whereas the placebo group showed minimal change, demonstrating efficacy beyond placebo effects.

Several devices currently offer bimodal neuromodulation, including the Lenire device by Neuromod (headphones with mild electrical tongue stimulation), the Neosensory Duo (headphones with tactile stimulation via a wristband), and the Auricle device (headphones with somatosensory input via electrodes on the ear). The Lenire device stands out due to multiple large-scale clinical trials demonstrating safety and effectiveness.

In the most recent FDA trial (TENT-A3, 2024) evaluating the Lenire device, participants first received 6 weeks of sound-only treatment, which had minimal effect.55,56 They then underwent 6 weeks of Lenire treatment combining auditory stimulation with gentle tongue stimulation. Following this combined treatment, 70.5% of patients with moderate or worse tinnitus experienced improvement exceeding the MCID on the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. These results were pivotal in obtaining FDA approval for Lenire and supporting its commercial availability.47 Treatment is typically home-based and guided by an audiologist.

Combines headphones with gentle tongue stimulation, allowing home-based auditory and somatosensory therapy during daily activities.

The Lenire device is useful for patients with normal hearing, as it directly targets tinnitus symptoms without relying on amplification. It has demonstrated effectiveness across a broad range of patients, including those with hearing loss, where it can be used as an adjunct to conventional amplification. For patients with hearing loss, hearing aids remain a priority to support communication and reduce tinnitus aggravation, though Lenire may complement treatment when appropriate. As of now, Lenire is available in clinics across the United States and Europe. While specific timelines for availability in Canada have not been confirmed, Neuromod's spokesperson has indicated that Lenire should be available in Canada soon.

Ongoing Management of Tinnitus-Influencing Factors

Tinnitus can arise from multiple factors, so ongoing management involves audiologists regularly assessing and addressing these influences to support patients’ well-being and help them navigate changes, including temporary spikes or worsening of symptoms.

Somatosensory Influences

Muscle tension or movement in the neck, jaw, or head can modulate tinnitus through auditory-somatosensory interactions. Clinicians can identify these influences through patient history or observation of changes in tinnitus with specific actions.

- Examples include jaw clenching, TMJ disorders, or past head and neck injuries.

Referral to physiotherapists, dentists, or osteopaths may help reduce symptom severity.

Hearing Fluctuations and Noise Risks

Tinnitus can worsen with temporary hearing changes caused by conditions such as Ménière’s disease, ear infections, vestibular schwannoma, head injuries, or age-related hearing loss. Noise exposure, from loud events or frequent headphone use, may also temporarily increase tinnitus loudness. Educating patients about these fluctuations, reassuring them that symptoms often stabilize, and emphasizing safe listening practices are key strategies for relapse prevention.

- Emphasize hearing protection and safe listening practices to reduce risk and stress.

Mental Health Factors

Anxiety, depression, PTSD, and sleep disturbances can intensify tinnitus, creating a bidirectional cycle where symptoms amplify stress, and stress worsens tinnitus.3,57 Cognitive distortions and maladaptive or safety-seeking behaviors may further exacerbate symptoms.58

- Examples include constantly monitoring tinnitus, excessive reliance on earplugs or headphones to mask tinnitus, avoidance of social settings for fear of aggravating symptoms

- Stress management techniques such as mindfulness, deep breathing, or progressive muscle relaxation can reduce emotional strain, improve sleep, and promote adaptive coping.

Lifestyle Considerations

Lifestyle choices also influence tinnitus. Alcohol, smoking, recreational drugs, and caffeine may worsen or, in some cases, improve symptoms depending on the patient. Discussing these factors helps guide adjustments that support better tinnitus management.

Referral Pathways and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Patients with suspected objective, pulsatile, or secondary tinnitus should be promptly referred to a specialist, including an otolaryngologist, neuroradiologist, or vascular specialist, for accurate diagnosis and management. Those experiencing somatosensory modulation may benefit from referral to a physiotherapist, dentist, otolaryngologist, or osteopath, as targeted interventions can help reduce tinnitus severity.

While addressing medical and somatosensory contributors is essential, clinicians must also recognize the influence of psychological factors, as emotional well-being plays a critical role in tinnitus perception and recovery. Discussions about mental health should be approached with sensitivity, using supportive language that encourages patients to share tinnitus-related distress without stigma.59–61 Audiologists can focus on cognitive, behavioural, and emotional aspects of well-being, but should avoid diagnostic labels such as “anxiety,” or “mental illness” since they are not authorized to diagnose or communicate mental health conditions.62

For patients who make limited progress or struggle to habituate despite individualized audiological care, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) can provide significant benefit. Audiologists can introduce elements of CBT within their scope—such as helping patients normalize tinnitus, regain a sense of control, and use relaxation or sound-enrichment strategies to reduce attention on the symptom. However, when these measures are insufficient, referral to a psychologist or cognitive behavioural therapist is warranted. Psychological factors such as anxiety, hypervigilance, or depression can reinforce tinnitus as a perceived threat, obstructing habituation and reducing the effectiveness of audiological care. CBT directly addresses these challenges by helping patients modify unhelpful thought patterns, reduce safety-seeking behaviours, and develop more adaptive coping approaches, ultimately lowering distress and improving quality of life.

Moving Forward with Comprehensive Treatment Plan

Tinnitus management is not about a quick fix or relying solely on amplification devices. It requires a structured, patient-centred framework that integrates informational counseling, amplification solutions, sound enrichment strategies, bimodal neuromodulation (if available), ongoing management of tinnitus-influencing factors, cognitive behavioural therapy, and timely referrals. Together, these components address multiple dimensions of the patient’s experience, creating a pathway toward relief, reassurance, and improved quality of life.

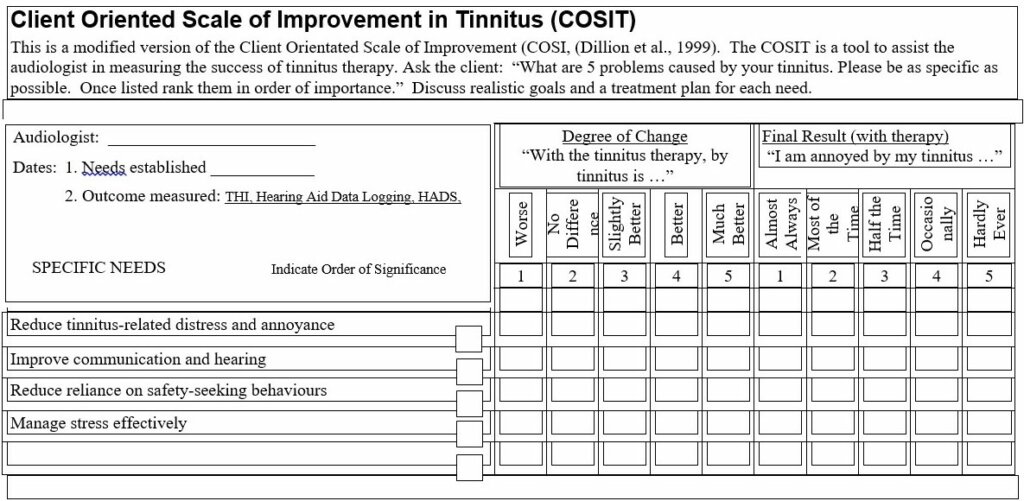

A central element is a comprehensive treatment plan that defines meaningful goals and tracks progress over time. Tools such as the Client-Oriented Scale of Improvement for Tinnitus (COSI-T) help patients identify their main concerns and measure perceived improvement.63 Long-term goals should focus on reducing tinnitus-related distress, improving daily functioning, and incorporating strategies such as sound enrichment to support ongoing management, rather than promising symptom elimination.

To support these long-term goals, clinicians can outline actionable steps such as ongoing counseling, fitting hearing aids, and addressing safety-seeking behaviours. Stress management techniques, including deep breathing, mindfulness, and progressive muscle relaxation, can further reduce anxiety, muscle tension, and sleep disruption. When needed, clinicians can facilitate referrals to additional medical or psychological support to ensure holistic, coordinated care.

Patient-Centered Goals for Tinnitus Management.

References

- Cima RFF, Mazurek B, Haider H, Kikidis D, Lapira A, Noreña A, Hoare DJ. A multidisciplinary European guideline for tinnitus: diagnostics, assessment, and treatment. HNO. 2019 Mar;67(Suppl 1):10-42. English. doi: 10.1007/s00106-019-0633-7. PMID: 30847513.

- Jastreboff PJ. Phantom auditory perception (tinnitus): mechanisms of generation and perception. Neurosci Res. 1990 Aug;8(4):221-54. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(90)90031-9. PMID: 2175858.

- Pineault, Dany (2024). The bidirectional association between tinnitus & mental well-being: clinical implications for audiologists. Audiologist Today, April 2024 - Volume 11 - Issue 2. https://canadianaudiologist.ca/13192-2/?output=pdf

- Tunkel DE, Bauer CA, Sun GH, Rosenfeld RM, Chandrasekhar SS, Cunningham ER Jr, Archer SM, Blakley BW, Carter JM, Granieri EC, Henry JA, Hollingsworth D, Khan FA, Mitchell S, Monfared A, Newman CW, Omole FS, Phillips CD, Robinson SK, Taw MB, Tyler RS, Waguespack R, Whamond EJ. Clinical practice guideline: tinnitus executive summary. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014 Oct;151(4):533-41. doi: 10.1177/0194599814547475. PMID: 25274374.

- Wu V, Cooke B, Eitutis S, Simpson MTW, Beyea JA. Approach to tinnitus management. Can Fam Physician. 2018 Jul;64(7):491-495. PMID: 30002023; PMCID: PMC6042678.

- Dobie, R.A. (2004) Overview: suffering from tinnitus. In: Snow JB, ed. Tinnitus: Theory and Management. Lewiston, New York: BC Decker Inc., 1–7.

- Sheppard A, Ishida I, Holder T, Stocking C, Qian J, Sun W. Tinnitus Assessment and Management: A Survey of Practicing Audiologists in the United States and Canada. J Am Acad Audiol. 2022 Feb;33(2):75-81. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1736576. Epub 2022 Sep 1. PMID: 36049753.

- Henry JA, Piskosz M, Norena A, Fournier P. Audiologists and Tinnitus. Am J Audiol. 2019 Dec 16;28(4):1059-1064. doi: 10.1044/2019_AJA-19-0070. Epub 2019 Nov 5. PMID: 31689367.

- Ramage-Morin PL, Banks R, Pineault D, Atrach M. Tinnitus in Canada. Health Rep. 2019 Mar 20;30(3):3-11. doi: 10.25318/82-003-x201900300001-eng.

- Tinnitus Retraining Therapy Trial Research Group; Scherer RW, Formby C. Effect of Tinnitus Retraining Therapy vs Standard of Care on Tinnitus-Related Quality of Life: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 Jul 1;145(7):597-608. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.0821. PMID: 31120533; PMCID: PMC6547112.

- English K. Guidance on Providing Patient-Centered Care. Semin Hear. 2022 Jul 26;43(2):99-109. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-1748834. PMID: 35903078; PMCID: PMC9325083.

- Newman CW, Sandridge SA, Jacobson GP. Psychometric adequacy of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) for evaluating treatment outcome. J Am Acad Audiol. 1998 Apr;9(2):153-60. PMID: 9564679.

- Meikle MB, Henry JA, Griest SE, Stewart BJ, Abrams HB, McArdle R, Myers PJ, Newman CW, Sandridge S, Turk DC, Folmer RL, Frederick EJ, House JW, Jacobson GP, Kinney SE, Martin WH, Nagler SM, Reich GE, Searchfield G, Sweetow R, Vernon JA. The Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI): development of a new clinical measure for chronic, intrusive tinnitus. Ear Hear. 2012 Mar-Apr;33(2):153-76. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31822f67c0. Erratum in: Ear Hear. 2012 May;33(3):443. PMID: 22156949.

- Henry JA, Griest S, Zaugg TL, Thielman E, Kaelin C, Galvez G, Carlson KF. Tinnitus and Hearing Survey (THS): a screening tool to differentiate bothersome tinnitus from hearing difficulties. Am J Audiol. 2015 Mar;24(1):66-77. doi: 10.1044/2014_AJA-14-0042. PMID: 25551458; PMCID: PMC4689225.

- Raj-Koziak D, Gos E, Swierniak W, Rajchel JJ, Karpiesz L, Niedzialek I, Wlodarczyk E, Skarzynski H, Skarzynski PH. Visual Analogue Scales (VAS) as a Tool for Initial Assessment of Tinnitus Severity: Psychometric Evaluation in a Clinical Population. Audiol Neurootol. 2018;23(4):229-237. doi: 10.1159/000494021. Epub 2018 Nov 15. PMID: 30439712; PMCID: PMC6381860.

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002 Feb;52(2):69-77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3. PMID: 11832252.

- Pineault, Dany. (2020, September 24). Assessing and Managing COVID-19 related Tinnitus. Phonak Audiology Blog [Clinical Practice]. https://audiologyblog.phonakpro.com/assessing-and-managing-covid-19-related-tinnitus/

- Baguley D, Fagelson M. Tinnitus : clinical and research perspectives. Bartnik G M. Managing tinnitus in adults: audiological strategies (pp. 287-308). Plural Publishing (2016).

- Beukes EW, Andersson G, Fagelson M, Manchaiah V. Audiologist-Supported Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Tinnitus in the United States: A Pilot Trial. Am J Audiol. 2021 Sep 10;30(3):717-729. doi: 10.1044/2021_AJA-20-00222. Epub 2021 Aug 25. PMID: 34432984; PMCID: PMC8642102.

- Liu YQ, Chen ZJ, Li G, Lai D, Liu P, Zheng Y. Effects of Educational Counseling as Solitary Therapy for Chronic Primary Tinnitus and Related Problems. Biomed Res Int. 2018 Jun 26;2018:6032525. doi: 10.1155/2018/6032525. PMID: 30046602; PMCID: PMC6038678.

- Cima RFF, van Breukelen G, Vlaeyen JWS. Tinnitus-related fear: Mediating the effects of a cognitive behavioural specialised tinnitus treatment. Hear Res. 2018 Feb;358:86-97. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2017.10.003. Epub 2017 Oct 12. PMID: 29133012.

- American Tinnitus Association. (2017). The intake process for people with tinnitus. ATA Summer 2017 Newsletter. https://ata.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Summer-2017-16.pdf

- Pineault, Dany. (2021). Tinnitus: Counseling Strategies to Help Your Patients. Phonak Audiology Blog [Clinical Practice]. https://audiologyblog.phonakpro.com/tinnitus-counseling-strategies-to-help-your-patients/

- Fuller T, Cima R, Langguth B, Mazurek B, Vlaeyen JW, Hoare DJ. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for tinnitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Jan 8;1(1):CD012614. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012614.pub2. PMID: 31912887; PMCID: PMC6956618.

- Henry JA, Roberts LE, Caspary DM, Theodoroff SM, Salvi RJ. Underlying mechanisms of tinnitus: review and clinical implications. J Am Acad Audiol. 2014 Jan;25(1):5-22; quiz 126. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.25.1.2. PMID: 24622858; PMCID: PMC5063499.

- McKenna L, Handscomb L, Hoare DJ, Hall DA. A scientific cognitive-behavioral model of tinnitus: novel conceptualizations of tinnitus distress. Front Neurol. 2014 Oct 6;5:196. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00196. PMID: 25339938; PMCID: PMC4186305.

- Shore S, Zhou J, Koehler S. Neural mechanisms underlying somatic tinnitus. Prog Brain Res. 2007;166:107-23. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)66010-5. PMID: 17956776; PMCID: PMC2566901.

- Goodman, M. (2002). The Iceberg Model. Innovation Associates Organizational Learning. Hopkinton, MA. Retrieved from https://files.ascd.org/staticfiles/ascd/pdf/journals/ed_lead/el200910_kohm_iceberg.pdf

- Oosterloo BC, de Feijter M, Croll PH, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, Luik AI, Goedegebure A. Cross-sectional and Longitudinal Associations Between Tinnitus and Mental Health in a Population-Based Sample of Middle-aged and Elderly Persons. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021 Aug 1;147(8):708-716. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2021.1049. PMID: 34110355; PMCID: PMC8193541.

- Herr RM, Bosch JA, Theorell T, Loerbroks A. Bidirectional associations between psychological distress and hearing problems: an 18-year longitudinal analysis of the British Household Panel Survey. Int J Audiol. 2018 Nov;57(11):816-824. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2018.1490034. Epub 2018 Jul 27. PMID: 30052099.

- Pineault, D. (2025, September). A foundational overview of tinnitus for hearing care professionals [Mini-course]. Pacific Audiology Group.

- Widex. (2023, October 18). Patient Evaluation with Dr. Dany Pineault(No. 3) [Audio podcast episode]. In Sound like no other. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DaIhUAIl-_g&t=221s

- Sanders, P. J., Nielsen, R. M., Jensen, J. J., & Searchfield, G. D. (2023). Hearing aids with tinnitus sound support reduce tinnitus severity for new and experienced hearing aid users. Frontiers in Audiology and Otology, 1, 1238164. https://doi.org/10.3389/fauot.2023.1238164

- Simonetti P, Vasconcelos LG, Gândara MR, Lezirovitz K, Medeiros ÍRT, Oiticica J. Hearing aid effectiveness on patients with chronic tinnitus and associated hearing loss. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2022 Nov-Dec;88 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):S164-S170. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2022.03.002. Epub 2022 May 20. PMID: 35729042; PMCID: PMC9761006.

- Yakunina N, Lee WH, Ryu YJ, Nam EC. Tinnitus Suppression Effect of Hearing Aids in Patients With High-frequency Hearing Loss: A Randomized Double-blind Controlled Trial. Otol Neurotol. 2019 Aug;40(7):865-871. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000002315. PMID: 31295199.

- Araujo Tde M, Iório MC. Effects of sound amplification in self-perception of tinnitus and hearing loss in the elderly. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2016 May-Jun;82(3):289-96. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2015.05.010. Epub 2015 Oct 16. PMID: 26541231; PMCID: PMC9444603.

- Pereira-Jorge MR, Andrade KC, Palhano-Fontes FX, Diniz PRB, Sturzbecher M, Santos AC, Araujo DB. Anatomical and Functional MRI Changes after One Year of Auditory Rehabilitation with Hearing Aids. Neural Plast. 2018 Sep 10;2018:9303674. doi: 10.1155/2018/9303674. PMID: 30275823; PMCID: PMC6151682.

- Henry JA, McMillan G, Dann S, Bennett K, Griest S, Theodoroff S, Silverman SP, Whichard S, Saunders G. Tinnitus Management: Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Extended-Wear Hearing Aids, Conventional Hearing Aids, and Combination Instruments. J Am Acad Audiol. 2017 Jun;28(6):546-561. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.16067. PMID: 28590898.

- Bovo R, Ciorba A, Martini A. Tinnitus and cochlear implants. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2011 Feb;38(1):14-20. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2010.05.003. Epub 2010 Jun 26. PMID: 20580171.

- Kam ACS. Efficacy of Amplification for Tinnitus Relief in People With Mild Hearing Loss. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2024 Feb 12;67(2):606-617. doi: 10.1044/2023_JSLHR-23-00031. Epub 2024 Jan 25. PMID: 38271299.

- McNeill C, Távora-Vieira D, Alnafjan F, Searchfield GD, Welch D. Tinnitus pitch, masking, and the effectiveness of hearing aids for tinnitus therapy. Int J Audiol. 2012 Dec;51(12):914-9. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2012.721934. Epub 2012 Nov 5. PMID: 23126317.

- Shetty HN, Pottackal JM. Gain adjustment at tinnitus pitch to manage both tinnitus and speech perception in noise. J Otol. 2019 Dec;14(4):141-148. doi: 10.1016/j.joto.2019.05.002. Epub 2019 May 24. PMID: 32742274; PMCID: PMC7387839.

- Pienkowski, Martin PhD. Sound Therapies for Tinnitus and Hyperacusis. The Hearing Journal 72(1):p 22,23, January 2019. | DOI: 10.1097/01.HJ.0000552752.74488.07.

- Henry, J. A. (2015). Validation of a Novel Combination Hearing Aid and Tinnitus Device. National Center for Rehabilitative Auditory Research. Retrieved from https://www.ncrar.research.va.gov/Publications/Documents/ValidationOfNovelCombHA-TinnitusDevice.pdf

- Hoare, D. J., Searchfield, G. D., El Refaie, A., & Henry, J. A. (2014). Sound therapy for tinnitus management: Practicable options. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 25(1), 62-75. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24622861/

- Theodoroff, S. M., Carlson, K. F., Reavis, K. M., Henry, J. A., Folmer, R. L., Zaugg, T. L., Quinn, C. M., & Thielman, E. J. (2023). History of tinnitus research at the VA National Center for Rehabilitative Auditory Research (NCRAR), 1997–2021: Studies and key findings. Seminars in Hearing. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-1770140.

- Pryce, Helen PD (Health); Munir, Shameela. The Role of Sound Therapies in Tinnitus Care. The Hearing Journal 74(3):p 14,15, March 2021. | DOI: 10.1097/01.HJ.0000737568.97962.1e

- Sereda M, Xia J, El Refaie A, Hall DA, Hoare DJ. Sound therapy (using amplification devices and/or sound generators) for tinnitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Dec 27;12(12):CD013094. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013094.pub2. PMID: 30589445; PMCID: PMC6517157.

- Fuller T, Cima R, Langguth B, Mazurek B, Vlaeyen JW, Hoare DJ. Cognitive behavioural therapy for tinnitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Jan 8;1(1):CD012614. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012614.pub2. PMID: 31912887; PMCID: PMC6956618.

- Kaneko Y, Oda Y, Goto F. Two cases of intractable auditory hallucination successfully treated with sound therapy. Int Tinnitus J. 2010;16(1):29-31. PMID: 21609910.

- Munir S, Pryce H. How can sound generating devices support coping with tinnitus? Int J Audiol. 2021 Apr;60(4):312-318. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2020.1827307. Epub 2020 Oct 1. PMID: 33000652.

- HandscombL (2006). Use of bedside sound generators by patients with tinnitus-related sleeping difficulty: which sounds are preferred and why? Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 556:59-63. https://doi.org/10.1080/03655230600895275

- Marks KL, Martel DT, Wu C, et al. Auditory-somatosensory bimodal stimulation desynchronizes brain circuitry to reduce tinnitus in guinea pigs and humans. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10(422):eaal3175. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aal3175

- Jones GR, Martel DT, Riffle TL, Errickson J, Souter JR, Basura GJ, Stucken E, Schvartz-Leyzac KC, Shore SE. Reversing Synchronized Brain Circuits Using Targeted Auditory-Somatosensory Stimulation to Treat Phantom Percepts: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Jun 1;6(6):e2315914. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.15914. PMID: 37266943; PMCID: PMC10238951.

- Boedts M, Buechner A, Khoo SG, Gjaltema W, Moreels F, Lesinski-Schiedat A, Becker P, MacMahon H, Vixseboxse L, Taghavi R, Lim HH, Lenarz T. Combining sound with tongue stimulation for the treatment of tinnitus: a multi-site single-arm controlled pivotal trial. Nat Commun. 2024 Aug 19;15(1):6806. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-50473-z. PMID: 39160146; PMCID: PMC11333749.

- Conlon B, Hamilton C, Meade E, Leong SL, O Connor C, Langguth B, Vanneste S, Hall DA, Hughes S, Lim HH. Different bimodal neuromodulation settings reduce tinnitus symptoms in a large randomized trial. Sci Rep. 2022 Jun 30;12(1):10845. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-13875-x. Erratum in: Sci Rep. 2023 Jul 10;13(1):11152. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-38312-5. PMID: 35773272; PMCID: PMC9246951.

- Pineault, D. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health and People with Hearing Problems, The Hearing Journal: March 2021 - Volume 74 - Issue 3 - p 6.

- Budd RJ, Pugh R. Tinnitus coping style and its relationship to tinnitus severity and emotional distress. J Psychosom Res. 1996 Oct;41(4):327-35. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(96)00171-7. PMID: 8971662.

- Graham, B. (2022, November 10). How can We Normalize Talking about Mental Health. The Paper Gown. Retrieved from https://www.zocdoc.com/blog/how-can-we-normalize-talking-about-mental-health/

- Knaak S, Mantler E, Szeto A. Mental illness-related stigma in healthcare: Barriers to access and care and evidence-based solutions. Health Manage Forum. 2017 Mar; 30(2):111-116. doi: 10.1177/0840470416679413. Epub 2017 Feb 16. PMID: 28929889; PMCID: PMC5347358.

- Substance abuse and Mental service Administration. (n.d.). How to talk about Mental Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human services. https://www.samhsa.gov/mental-health/how-to-talk

- Pineault, D. (2024, November 10). From tinnitus to musical hallucinations: Navigating complex auditory symptoms. Canadian Audiologist. Retrieved from https://canadianaudiologist.ca/from-tinnitus-to-musical-hallucinations-navigating-complex-auditory-symptoms/

- Searchfield GD. A Client Oriented Scale of Improvement in Tinnitus for Therapy Goal Planning and Assessing Outcomes. J Am Acad Audiol. 2019 Apr;30(4):327-337. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.17119. Epub 2018 Feb 15. PMID: 30461417.