With All the Modern Hearing Aid Technology and Processing, Is It Still Necessary to Conduct LDLs for My Patients?

Editor’s Note: While this Quick Answers is a bit longer than others, the answer may be quick, but getting there may require some background. The Quick Answer regarding whether we should measure patient-specific LDLs is “Yes”, but I think that reading Gus Mueller’s Quick Answer below will be much more fulfilling.

The short Quick Answer is “Most Certainly.” There are good reasons why frequency-specific LDLs have long been a component of best practice, including the recent APSO hearing aid fitting standard.1

Back in January of 1994, when I launched the Page Ten column in The Hearing Journal, I recruited Ruth Bentler to help me write the article, “Measurement of TD—How loud is allowed?” 2 Linear fittings were still fairly common at that time. Our focus was mostly on reminding audiologists to ensure the output was not too high. Around this same time, the IHAFF group was putting together a fitting method that included VIOLA (Visual Input-Output Locator Algorithm), developed by Robyn Cox, a member of our IHAFF group. VIOLA was a software tool, that after entering the patient’s loudness measures, allowed us to determine the AGCo setting, and then adjust WDRC kneepoints and ratios to package soft, average and loud inputs appropriately within the individual’s residual dynamic range. I must say, it was a great way to understand the workings of WDRC, and actually was quite fun. But things change. Today, many if not most audiologists rely on their favorite manufacturer to get the aided loudness right. This can be risky.

First, there are two basic factors to remember. Going back to the work of Bentler and Cooley3, we’re reminded that it’s very difficult to predict a person’s LDL from their pure-tone hearing loss. Their testing of over 500 ears found that for hearing losses in the 40-60 dB range (common for hearing aid fittings), the LDL range was ~50 dB, and only 32% were within 5 dB of the average. A second factor to remember is that while we certainly don’t want the aided output to exceed the LDL, we also don’t want it to be significantly below it, as that reduces useful headroom—it’s a Goldilocks thing.

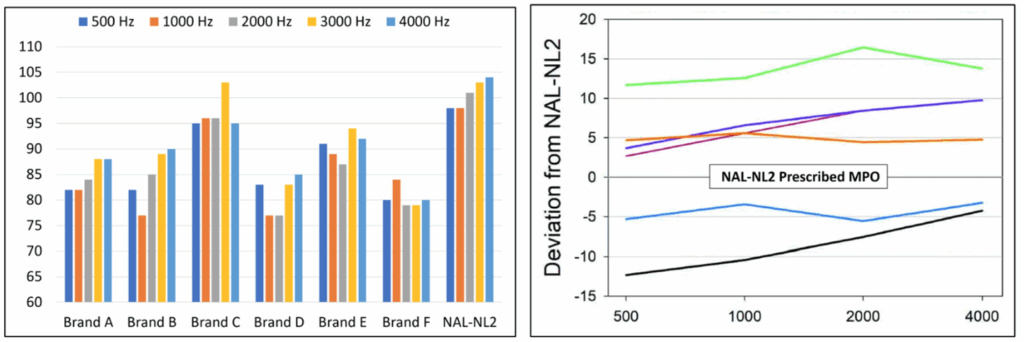

This prompts me to discuss a project I did a few years ago with Elizabeth Stangl and Yu-Hsiang Wu from the University Iowa4. We assessed the maximum output of the premier hearing aid from the top six leading brands across different software configurations. Testing was conducted in a 2-cc coupler, using a 90-dB swept tone. What you see in the left panel of Figure 1 is the maximum output of the six products for different frequencies when we selected “NAL-NL2” in the fitting software for a common hearing loss (30 dB in the lows, gradually sloping to 60 dB at 4000 Hz). Also shown is the prescriptive MPO of the NAL-NL2 for this hearing loss.

Perhaps the most noticeable aspect of these data is that, except for the Brand C product, the measured output is significantly below the predicted MPO of the NAL-NL2 algorithm (see the far-right data on the chart). In particular, Brand D and F are ~20 dB below—assuming this patient is “average,” this would be restricting considerable headroom, which in most cases is useful. Why would a manufacturer choose a maximum output this low, you might ask?

We did some additional testing; what you might do for your NAL-NL2 verification using probe-microphone measures. We found that although we selected the “NAL-NL2” fitting algorithm in each manufacturer’s software, only Brand C had REAR outputs that were close to the NAL-NL2 targets. Brand D, for example, for a 65 dB input (ISTS), had an REAR ~10-15 dB below the NAL-NL2 targets (see Figure 7 a-b in Mueller et al.4). This prompted us to go back to the 2-cc coupler and conduct testing at max volume-control gain, rather than the manufacturer’s selected gain, for each instrument for the NAL-NL2 setting—could the patients fix the problem themselves by simply turning up gain? This only raised the MPO by ~5 dB (90-dB swept tone, re: 2-cc coupler) for the products with the low MPO. This shows that the MPO is being controlled by the WDRC kneepoints and/or ratios. While we usually think of under-fitting as having the unfortunate consequences of reduced audibility, it appears that restricted headroom is also a common problem—maybe not the first thing that comes to mind when troubleshooting a fit issue. Of course, to properly fix it, we need to know the patient’s LDLs.

Shown in the right panel of Figure 1 is a related, but different problem. These data did not involve testing. We simply went to each manufacturer’s software, and recorded the MPO shown for a NAL-NL2 fitting for the sample audiogram. While one would assume that if you select the NAL-NL2, the software would reflect these prescribed values, this does not seem to be true in most cases—note differences of over 20 dB between the lowest and highest settings—the Brand with the green curve is 12-15 dB above what is recommended by the NAL-NL2.

Getting back to the original question and to summarize, we know that the variability of individual LDLs is too great to predict from pure-tone thresholds, we know that the “first fit” of many products unnecessarily restricts headroom, and we know that the MPO selected by many manufacturers seems to be unrelated to the fitting method selected. This all boils down to a simple answer: Measure individual frequency-specific LDLs, use these values to program the hearing aids, and verify with traditional REAR speech mapping and REAR85 measures. When making adjustments, remember that it might be the WDRC, not the AGCo, that controls the maximum output.

If you haven’t thought about measuring LDLs, RETSPL corrections, and using these values to program hearing aids for a while, you can find a review at Mueller 2011a5 and Mueller 2011b6. Brian Taylor and I also recently provided a step-by-step procedure for the testing and coupler corrections7.

Bottom line: An otherwise “good” fitting can be a failure if the output isn’t set correctly. Depending on an outside source to do this for us can be risky. Getting it right is what we do!

References

- Mueller, H.G., Coverstone, J., Galster, J., Jorgensen, L., & Picou, E. (2021). 20Q: The new hearing aid fitting standard - A roundtable discussion. AudiologyOnline, Article 27938 Available at www.audiologyonline.com

- Mueller, H G, Bentler RA. (1994). Measurements of TD: How loud is allowed? The Hearing Journal. 47(1):10, 42-44.

- Bentler, R.A., & Cooley, L.J. (2001). An examination of several characteristics that affect the prediction of OSPL90 in hearing aids. Ear and Hearing, 22(1), 58-64.

- Mueller G, Stangl E, Wu Y-H. Comparing MPOs from six different hearing aid manufacturers: Headroom considerations. Hearing Review. 2021;28(4):10-16.

- Mueller HG. (2011a) How Loud is Too Loud? Using Loudness Discomfort Level Measures for Hearing Aid Fitting and Verification, Part 1. AudiologyOnline. Available at www.audiologyonline.com

- Mueller HG (2011b) How Loud is Too Loud? Using Loudness Discomfort Level Measures for Hearing Aid Fitting and Verification, Part 2. AudiologyOnline. Available at www.audiologyonline.com

- Taylor, B. & Mueller, H. G. (2023). Research QuickTakes Volume 6 (Pt. 1): hearing aid fitting toolbox —important pre-fitting measures. AudiologyOnline, Article 28707. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com