Other People’s Ideas

Calvin Staples, MSc, will be selecting some of the more interesting blogs from HearingHealthMatters.org which now has almost a half a million hits each month. This blog is the most well read and best respected in the hearing health care industry and Calvin will make a regular selection of some of the best entries for his column, Other People’s Ideas.

Over the past several years I have regularly selected blogs from the hearinghealthmatters.org site that focus on PSAPs/Hearables. I often wonder how they might change our models of delivery or patient access to devices and services. I think the reason I continually come back to this topic because I find it very interesting, somewhat controversial and most of all because it smells like change. What impact will PSAP/hearable devices have on the practice of audiology? I am truly asking this question. It would be nice to see what readers of Canadian Audiologist think will come of the PCAST report; as I have am completely uncertain. I do believe as audiologists we need to continue to adapt and change or risk playing a smaller role in the future. I have submitted a handful of blogs that I thought could initiate conversation.

On The PCAST Report And The FDA Hearings

Downstream Consequences of Aging is a bi-monthly series written by guest columnist Barbara Weinstein, PhD. Today’s post is especially timely, on the heels of the IOM final report and anticipating the FDA review process that generated 160 stakeholder comments.1

On the PCAST Report and the FDA Hearings

Originally posted on June 7, 2016 ·

The focus of the public workshop hosted by the FDA on April 21, entitled “Streamlining for Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) for Hearing Aids” was the recent report from the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST).

The PCAST report and the FDA hearing prompted responses from stakeholders across the quality enterprise (Figure 1) including the Hearing Loss Association of America (HLAA), American Public Health Association (APHA), the Hearing Industries Association (HIA), the Consumer Technology Association(CTA), and professional associations representing audiologists including ADA, ASHA, and AAA.2

Figure 1. Stakeholders in the Hearing Health Quality Enterprise References

Can’t We All Just Get Along?

The responses from the stakeholders were mixed, hailed by some groups and denounced by others. To facilitate a meeting of the minds between the different organizations, I would like to play mediator in an attempt to amicably resolve some of the differences across stakeholders orienting the focus on responsible innovation and the consumers we serve.

All parties agree that:

- Untreated hearing loss is a public health issue with medical, social and economic consequences which increase

- health care expenditures

- rate of hospitalizations

- risks for functional limitations, morbidity and mortality.

- The needs of the majority of persons with age related hearing loss are not being met especially those with mild to moderate hearing loss.

- Hearing aid use is dose related, greatest among persons with moderate to severe hearing loss.

- There are social barriers associated with hearing loss and hearing aid use.

- There are marketplace changes marked by a revolution in digital technology and price reductions in consumer electronics.

- People are living longer, retiring later, remaining in the workforce longer.

- Social engagement is critical to quality of life and mortality.

Stakeholder’s Solutions Differ

Stakeholders are driven by the missions of their organizations and therefore differ in their perspective on hearing health care and its solutions.

American Public Health Association

The APHA works to optimize the health of all persons and all communities and to advance prevention, to reduce health disparities, and to promote wellness. Working with the CTA foundation, the mission of the CTA is to empower older adults and persons with disabilities to promote accessibility of technologies designed to enhance well-being.

Hearing Loss Association of America

The HLAA advocates for the consumer with hearing loss and its strategic intent is to both eradicate the stigma of hearing loss and to help persons with hearing loss gain access to resources and affordable technology which work seamlessly allowing them to live successfully, without having to compromise.

Hearing Industries Association

Recognizing the importance of hearing health to health, productivity, and well being, the HIA coordinates with the Better Hearing Institute (BHI) to conduct research and hearing health education with the goal being to help people with hearing loss to benefit from treatment.

Audiology Professional Membership Organizations

Representing audiologists in a variety of settings, the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA), the American Academy of Audiology (AAA), and the Academy of Doctors of Audiology (ADA) have competing missions which have worked to the disadvantage of the consumer and to the advantage of the remaining stakeholders shown in Figure 1 (with the exception of the HIA).

Representing audiologists working in a variety of settings, the AAA is dedicated to providing quality hearing care services through professional development, education, research, and increased awareness of hearing and balance disorders. Representing autonomous and private practitioners, the ADA is dedicated to the advancement of practitioner excellence, professional autonomy, high ethical standards, and sound business practices in the provision of quality audiologic care. Finally, the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) has as its mission the empowering of professionals in communication disorders through advancing science, setting standards, fostering excellence in professional practice, and advocating for members and those they serve.

Consumers Are Stakeholders, Too

The mission statements of our professional organizations rarely include the person with hearing loss. Yet, it is that person who should be the driver of the work for which I hold a passion — namely making a difference in the lives of persons with hearing loss and their communication partners. This, my friends and colleagues, could be a major reason that audiology is ripe for disruptive innovation.

So here is my take. Professionals and the associations to which we belong, must be driven by the “wants” and “needs” of the consumers we serve. Present day consumers are educated and savvy about available hearing health care interventions and are increasingly insistent on accessible and affordable hearing health care. Value based care is a buzz word, a driver of reimbursement systems, and private payers. When considering a treatment plan, our patients want to know what the service will cost, what he or she can expect based on firm data, and above all will want to be involved in decisions about their hearing healthcare.

Informed choice and treatment options based on patient readiness, communication challenges, ability and willingness to pay are integral in the present day hearing health care environment.

Use Evidence-Based Questions to Design and Align

In conclusion let’s reflect on how well-aligned the needs of our patients are with our goals as a profession. Consider my revisionist version of the expectations performance theory. Our expectations must be aligned with those of our patients. Our patients’ wishes regarding communicative priorities must be aligned with the patient reported outcomes on how they are functioning that we should be gathering.

By sharing the evidence that our patients’ needs are being met with stakeholders, the word of mouth about the good and important work we do will be positive and referrals should flow. The sustainability of our profession and treatments we advocate rely on the collective responsibility of all stakeholders.

The acceptability and desirability of marketable hearing health care products is key to our quality enterprise. Responsible innovation demands that we ask the right product-, process- and purpose questions. Examples of potential question of each type are:

Product question: “How might future products change to meet the needs of persons with age related hearing loss and optimize the skills of audiologists as the professionals of choice?”

Process question: “How should standards be drawn up and applied to protect consumers and professionals?”

Purpose question: “Are our motivations transparent and in the public interest3?”

It is a win-win for all stakeholders to close the gap between the proportion of persons with untreated age related hearing loss and the proportion of those who enjoy a measurably high quality of life as the result of hearing health care interventions purchased through audiologists.

We are part of the problem and part of the solution. Let’s change that balance and remain essential.

References & Footnotes

- Regulatory Requirements for Hearing Aid Devices and Personal Sound Amplification Products; Draft Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff; Availability.

- Blustein, J., & Weinstein, B. (2016). Opening the market for lower cost hearing aids: Regulatory change can improve the health of older Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 106:1032-1035.

- Stilgoe, J., Owen R., & Macnaghten, P. (2013). Developing a frame for responsible innovation. Research Policy. 42: 1568-1580.

Waiting for the Second Shoe (of Three)

Originally posted on May 31, 2016

Before we get started, a disclaimer: This post will name names – hearing aid products, a health insurance company, and hearing health care benefit programs. I have no financial or non-financial interests in any of the products/companies mentioned except as a subscriber to the GEHA national health insurance plan to which I make monthly premium payments.

Before we get started, a disclaimer: This post will name names – hearing aid products, a health insurance company, and hearing health care benefit programs. I have no financial or non-financial interests in any of the products/companies mentioned except as a subscriber to the GEHA national health insurance plan to which I make monthly premium payments.

About Those Shoes

- Shoe #1. On June 2, the IoM Committee on Accessible and Affordable Hearing Health Care for Adults released its report following four meetings over the past year that included presentations by consumers, researchers, clinicians, industry representatives and organizations representing consumers, clinicians, and the industry.

- Shoe #2. This report follows closely on the heels of the PCAST report which concluded that hearing aids are expensive and most folks don’t have access to them.

- Shoe #3. Yet to be heard from, is the FDA which held a workshop in April soliciting comments related to the “safety and effectiveness of air-conduction hearing aid devices” (read “PSAPs”). As of writing, the FDA has not announced a release date for their workshop report.

Two Epiphanies

Two events occurred in rather quick succession a couple of weeks ago that made me revisit the affordability and accessibility issue in general and the PCAST report in particular.

Framing or Misrepresentation of the Price Issue?

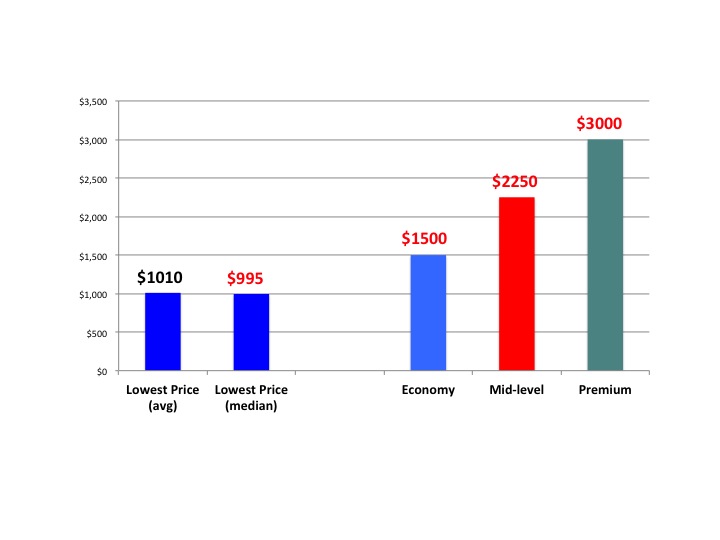

Fig 1. Average and median hearing aid prices of lowest priced hearing aids in the typical practice, as well as median prices for economy, mid-level, and premium hearing aid lines. (K. Strom, Hearing Review, May 2016).

The first was a Hearing Review blog by Karl Strom that provided a “sneak preview” of the 2016 dispensing survey to be published later this summer. What I found interesting in this report (in the context of PCAST) was the finding that the average cost of the lowest priced hearing aid was $1010 and its median cost was $995 (Figure 1).

By contrast, the PCAST reported that the average price of one hearing aid was $2,363, with premium models costing $2,898. It appears that the PCAST framed the hearing aid pricing issue at the extreme (high) end. I could accept this approach as a reasonable way to frame an issue (depending upon the point you wish to make) except for the fact that the PCAST then proceeded to compare the retail, bundled cost of a hearing aid with the discounted, unbundled cost of a hearing aid to the VA which they reported as $400. I would argue that the PCAST moved beyond framing the issue to misrepresenting it.

But Wait, Is There More?

The second event that got my attention was a mailing I received from my health insurance company (GEHA) offering deep discounts on hearing aids through a hearing care network called TruHearing. The discounts were impressive. According to the brochure, a standard option subscriber (like me) could obtain Widex Dream 220 hearing aids (average retail price of $3,880 per pair per the brochure) for $2390 a pair through TruHearing. Pretty good.

BUT WAIT, THERE’S MORE! My insurance company further discounts the pair an additional $1000 so that my cost is $1390 for the pair ($695 per hearing aid). If I were a high option subscriber, the discounts could be even deeper. For example, after the TruHearing and GEHA discounts, a pair of ReSound Linx2 hearing aids that retail for $4120 would cost me $500 for the pair – $250 per hearing aid.

BUT WAIT, THERE’S EVEN MORE! TruHearing distributes a company brand (manufacturer unknown) named “Chime.” Under the GEHA high option plan the TruHearing Chime 500 hearing aid will cost me $0. That’s right, folks – nothing, nada, zero, free. And, according to their brochure, the following services are available to me through any one of the 3,800 nationwide providers as part of any purchase under this program:

- 3 follow-up visits

- 45-day trial

- 3-year manufacturer warranty and 1-time loss and damage replacement

- 48 free batteries

Am I Just Special?

Maybe as a retired federal employee I’m a beneficiary of a unique program available to relatively few Americans. I did some on-line research, however, that took me down a rather deep rabbit hole where (perhaps not surprising to those of you in private practice).

I found an impressive list of insurers and benefit programs offering substantial discounts on hearing aid purchases to their subscribers. A partial list of hearing healthcare benefit programs that partner with insurers, employers, corporations, unions, consumer organizations, retirees, and managed care organizations include:

- HearUSA

- Amplifon Hearing Health Care (formerly HearPO)

- Epic Hearing Health Care

- American Hearing Aid Associates (AHAA)

- Hearing Care Solutions

- HEAR in America

- Hi HealthInnovations (United Health)

- American Hearing Benefits

In addition to those listed above, an impressive list of Blue Cross Blue Shield hearing care benefit programs was assembled by Florida audiologist, Dan Gardner and can be found on his website.

Redux: Price is Not the Barrier

Naturally, prices, discounts, co-pays, prices, services, products, eligibility, etc. will vary from one plan to another and it is not my purpose here to critically review these programs but, rather, to question the assumptions expressed in the press, by PCAST, and at the FDA and IOM hearings that hearing aid cost is the primary barrier responsible for their low utilization among those with hearing loss. Frankly, I don’t know what percentage of those who can benefit from hearing aids have access to hearing care benefit programs similar to those described above (not to mention access to discounted hearing aids provided by large retailers such as Costco) but I would argue that this is precisely the type of information that should have been researched by the PCAST and the IoM Committee. The PCAST didn’t; perhaps the IoM Committee has.

As Holly Hosford-Dunn suggests in her 4th of a 5-part series on barriers in the hearing aid industry, the primary barrier to increasing hearing aid utilization may not be price but, rather, “incomplete consumer information on the low end of the demand curve” and the “absence of adequate price transparency at all points in the supply chain.”

I’d like to think that the mailing I received from my insurance company marks the beginning of a trend to remove those barriers.

This is Part 16 of the Peeling the Onion series. Click here for Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9, Part 10, Part 11, Part 12, Part 13, Part 14, Part 15.

End of Barriers, Part 4

Originally posted May 17, 2016

This is the almost-final Econ 202 post on barriers that exist in the US hearing aid manufacturing and delivery system.1

Parts 1, 2 and 3 addressed regulatory requirements that discourage new entrants; legal and economic definitions of barrier to industry entry/exit; structural and strategic barriers in the hearing aid industry; and specific strategic barriers used by incumbent manufacturers in their competitive response against entry firms.

Today’s finale wonders whether hearing aid industry barriers have much relevance in the coming markets for ear devices.

Barriers May Not Matter

Monopolistic pricing of product (and services) only works if there are no close substitutes. (Karlin & Morduch, 2014).2

“Why scale a barrier if you can go around it?”

That’s the relevant question for competitors, new and incumbent, when considering new product spaces. Likewise, the question applies as new distribution channels run parallel or tangential to traditional hearing aid dispensation; or skip the dispensing part entirely.

The question is especially relevant in the current milieu of divergent definitions by the FDA and CTA of ear level devices and technologies loaded into those devices. The same can be said for its relevance to related social policy discussions ongoing within the FDA, PCAST, and IOM that put downward pressure on Price.

Natural Barriers

Could our little fortress of manufacturers and dispensers morph into something not too far afield of to what economists call a “natural monopoly”? That’s a situation where the market is too thin to sustain more than one competitor. A common example is the barber shop in a rural town, which can charge whatever it can get to cut hair. The populace and city fathers could bring in another barber to boost competition, but that would cost more than paying the going rate to the incumbent barber shop; plus the quality of hair cuts would probably go down when rates were cut.

True, our situation has more than one barber shop, but the shops all know each other, use the same equipment, swap employees, consolidate shops, and do the same hair cuts. No surprise if they happen to set similar, monopolistic, prices for products and services. And no surprise if the regulators and that 20% of traditional hearing aid consumers decide to maintain status quo if faced with the opportunity cost of subsidizing a shrinking industry that could be in decline.

Dwindling industries typically do not conduce competitive technological innovation. Monopolistic pricing is not a guaranteed boon for incumbents. Price has to cover average total costs of production in the long run–another way of saying that monopolies may not make enough money to maintain, much less fund large R&D programs.

It is possible to reap negative profit with monopolistic pricing and all bets are off if regulators force price down toward marginal cost level. Either way, the technological engine stalls, differentiation disappears, companies face shutdown and exit the market. If the remaining companies or the market become “too small or too limited, [they’ll] just become irrelevant and bypassed.“4

A Market to Ourselves

If 2015 and the 2016 AudiologyNow! exhibit floor are samples of what’s to come, PSAP and Hearable suppliers, big and small, may march past our barriers. For example, Samsung has yet to enter the hearing aid market, despite expectations to the contrary for the last year. In which case, the specialized, sequestered hearing aid industry and licensed distribution channel can stay fortified on The (Capitol) Hill. From there, they can watch from the ramparts as the hoards swarm by, far out of shooting range.

Which is not all bad. Besides peace in the valley and on The Hill, remaining manufacturers and licensed providers would still have their market of old: the static 20% of consumers who want to purchase specialized medical devices through licensed professionals in bricks and mortar settings.

If the 20% holds steady as the aging population grows, it’s sufficient to maintain a few competitors in the market. Even if the percentage declines as the aging population grows, there should still be enough demand in the market to maintain at least a couple technologically innovative competitors.

And that’s not so bad either. Regardless of politics and wallets, most of us can agree that having at least one product and group of experts in the market which offer a high-priced, superior technology, fitting and maintenance solution beats the alternative of a bunch of companies all producing low-cost, similar “basic” hearing aids for self fit as the only solution.

…sometimes a monopoly in a more technologically advanced product is better than a competitive market in an obsolete one. (Taylor, 2010)3

The One Thing That’s NOT a Barrier is Price

This space has spent years aggregating data to demonstrate what should be obvious from any perusal of the Internet or the local paper: hearing aids come at all price points from $399 up, even lower or free with some benefit plans. On the other side of the Demand curve, Consumers who want to drive out of the show room in a Mercedes-level hearing aid have been able to do so for a premium price increase of less than $60/year for the past 20 years.

It may be good politics but it’s bad economics to put the blame on Price.

Accordingly, Hearing Economics will beat this dead horse with a few links from its past, in hopes that somebody is reading this stuff. Notwithstanding stigma as a personal barrier, barriers other than Price are holding back the market, specifically:

- regulatory restrictions on the high end of the Demand curve

- incomplete consumer information on the low end of the Demand curve

- corporate credibility or lack thereof

- absence of price transparency at all points in the Supply chain

In Conclusion

Econ 202, “Barriers in the US hearing aid market”, is over and you’re all encouraged to enjoy your summer vacation. Here are your take-home points.

Price is not a barrier, but other barriers exist which:

- add to the wholesale and retail costs of hearing aids, but none excessively (and none exclusively);

- bestow incumbents with market power, enabling monopolistic pricing and societal costs;

- aren’t big enough to prevent market entry;

- allow incumbents to

- recover start up investment and other fixed costs through sales,

- may be of little consequence as technological changes grow the market;

- may protect a few remaining incumbents in a declining market.

grow productivity and reduce operating costs through mergers and acquisitions;

PS

Sorry, just kidding about vacation. Class is still in session till we get through next week’s post-script.

Meanwhile, I’m staging a strategic retreat to my bricks & mortar office to dispense high tech hearing aids under my state license to anyone who can scale the barrier to access.

References

- Although this series is limited to the US market, anticompetitive barriers and price effects are in discussion in other countries as well. France recently launched an investigation to see whether storming the hearing aid Bastille is in order to bring down prices.

- Karlin D & Morduch J. Monopolistic competition and oligopoly (Ch 15). Economics (1st Ed, 2014). NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Taylor JB. Monopoly (Ch 10). Principles of Microeconomics (7th ed, 2010). Mason, OH: Southwestern-Cengage Learning.

- Health care companies see scale as the only way to compete. NYTimes, 4/29/16.

Apple Receivers Patent for Headphones Using Bone Conduction to Improve Hearing in Noise

Originally posted by HHTM on June 9, 2016 ·

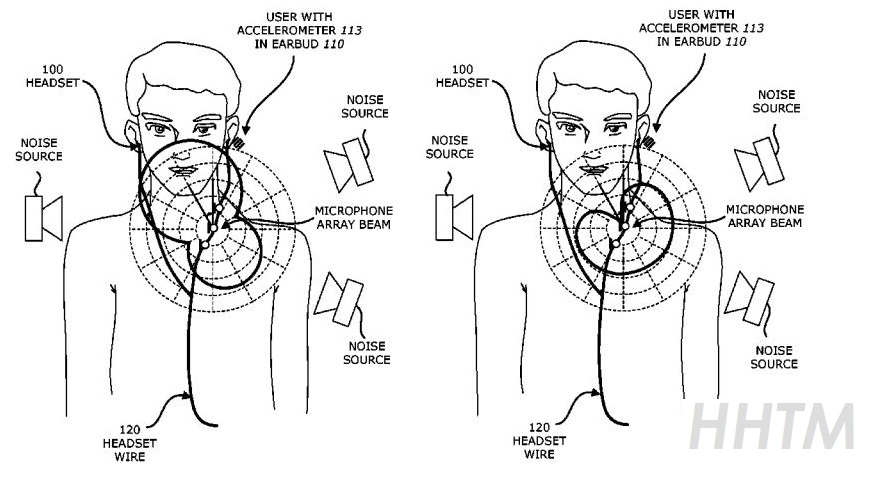

CUPERTINO, CALIFORNIA — Tech industry titan, Apple Inc (NASDAQ: AAPL), was awarded a patent this week by the US Trademark Office for a headset that utilizes bone conduction to deliver improved hearing in the presence of ambient noise. The patent,#9,363,596, was originally filed in 2013.

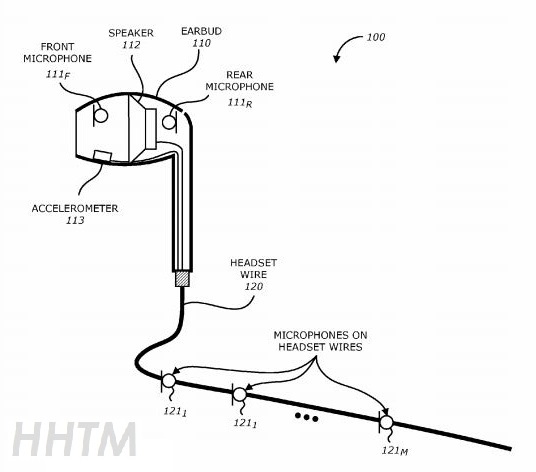

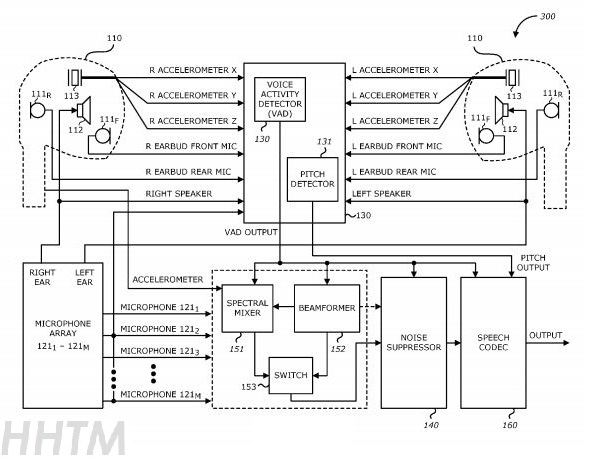

The earphone device uses an accelerometer-based voice activation detection and microphone array, which measures output signals and filters out non-vocal noise to help improve speech recognition over the ambient noise.

Will Tech Come With Next iPhone?

At this point it is unclear what Apple’s plans are in the future for the technology and whether or not it will end up in the next generation iPhone. The company’s patent abstract gives some insight into how the headphones are intended to work:

A method of improving voice quality in a mobile device starts by receiving acoustic signals from microphones included in earbuds and the microphone array included on a headset wire. The headset may include the pair of earbuds and the headset wire. An output from an accelerometer that is included in the pair of earbuds is then received. The accelerometer may detect vibration of the user’s vocal chords filtered by the vocal tract based on vibrations in bones and tissue of the user’s head. A spectral mixer included in the mobile device may then perform spectral mixing of the scaled output from the accelerometer with the acoustic signals from the microphone array to generate a mixed signal. Performing spectral mixing includes scaling the output from the inertial sensor by a scaling factor based on a power ratio between the acoustic signals from the microphone array and the output from the inertial sensor. Other embodiments are also described.

Within the patent filing were also several images indicating how the system works, as seen below:

Interested in the latest patent activity in the hearing industry? Don’t miss Holly Hosford-Dunn’s bi-monthly patent updates at Hearing Economics.

PCAST, PSAPs, and Likely Possibilities

Originally posted by HHTM on May 24, 2016

On May 12th, Brian Taylor placed a post on this website about Samsung and Apple perhaps influencing the hearing aid field. By now, everyone can probably discuss disruptive innovation. If you don’t know about this concept and its application to the “P-stuff” in the title, you have probably been off the grid a little too long. And, if you watched the FDA meeting on April 21st, you may have some interesting conclusions.

There is a concept that concerns “low hanging fruit”—people will deal first with problems, solutions, sales, etc. that involve the least effort. The parallel to the hearing aid industry is observable in that the industry serves at most 10-20% of the hearing impaired it seeks to help. This percentage has been stable for decades. Those not served evidently require more than those who are receiving benefit from our present service model.

No one can predict the future but that doesn’t stop anyone from stepping up to the plate. Will PSAPs and the PCAST change the field? How quickly? Ian Windmill had some good opinions in a recent 20Q on AudiologyOnline. Here are some more opinions—hopeful, and not all that contrary I suspect.

Recall the entry of the “Big Box” stores and the rise of consolidated sales groups in the HA industry. What were the effects on the industry? Even before these two disruptions, there were attempts to introduce PSAP-like devices into the hearing aid economy. The impact of past changes (disruptions) may have been substantial to some small companies and dispensers but hardly catastrophic to the industry.

If the past is any predictor, PSAPs will also have an effect on retail sales. But, this effect is likely to be minimal, at least in the near term. And, it will probably not disrupt manufacturers all that much. Pseudo-Data (in technical terms—reasonable guesses) in support of this position:

- Of 33-36 million hearing impaired people in the US, about 2-3 million people per year get “typical” hearing aids. About 85% get two instruments.

- So, the hearing aid industry in the US sells between 2-4 million devices per year (4 million would be about 7% of 60 million potential sales—3-4% of the hearing loss population).

- If PSAPs take away as much as 15% of the sales, that comes to about 600,000 units—a significant number but not fatal to conventional instrument sales. (Here are two important keys—what “fruit” is first lost and who loses the most?)

Does this mean that the “Big Seven, or Big 8, or Big However Many” will counter by substituting regular, lower-tier hearing aids with PSAP-like products—both likely to have the similar wholesale profit margins? While some manufacturers may venture into the OTC market, it seems likely that most will not disrupt their present profitable methods. Especially when there are non-OTC products that are close in wholesale price to PSAPs and will support the present delivery system. Of course, this argument then must evolve to treatment aspects—a topic crucial to audiologists.

Make no mistake; technology will go a long way toward solving hearing loss problems. Think of the past 20 years and make a compelling argument to the contrary. Would you expect that PSAPs would fail as often or more often than typical hearing aids? (If not a higher failure rate—Yikes!) When PSAPs evolve by adding adjustability, phone apps, or other modifications, these OTCs will become more like lower-tiered, conventional instruments. Of course, these revisions will also likely increase cost. And, some of these new PSAP users may seek help from a professional— help that will not be included in the PSAP purchase price. And, so on…

Returning to the “low-hanging fruit”, what do manufacturers of PSAPs expect? Do they think that there is a lot of potential for a product that ignores various levels of significant instruction and therapy? What is the real potential market for these DIY things? Surely no one is naïve enough to think that everyone needing but not using hearing aids would be a potential buyer and that they will buy one for each ear. If PSAPs are inexpensive, how many have to be sold to reap the kinds of profits necessary to stay in business? Just because a gigantic company participates doesn’t mean they don’t look on profit in the same manner as a smaller company.

It would seem likely that our present delivery system, in all its good and not-so-good aspects, will continue for the immediate future because it provides lots of help to lots of people. (Just because the delivery system perseveres does not mean it’s as good as it should be.) If Audiology adheres to the best practices in testing and rehabilitation, most dispensing audiologists will probably continue to prosper. It would be reasonable to predict a slow adaptation of the PSAP, but if we are thorough, compassionate, and apply the best of what we know and can do, audiologists will adapt to the change—just like we did with all those past changes. Even though painful, the adapting process might result in things getting done better.