Other People’s Ideas

Other People's Ideas

Calvin Staples, MSc, will be selecting some of the more interesting blogs from HearingHealthMatters.org which now has almost a half a million hits each month. This blog is the most well read and best respected in the hearing health care industry and Calvin will make a regular selection of some of the best entries for his column, Other People’s Ideas.

I recently read an ENT report that used the term vascular loop mass. Personally, I have never come across this and was not sure how this differentiated from an acoustic neuroma/vestibular schwannoma. Interestingly enough, my first stop on the old Googler landed me on the Hearing Health Matters site, which revealed the link below discussing vascular loops. The additional blogs focus on clinical topics that routinely come up in patient interactions that we rarely see significant exposure to in our training programs.

Vascular Loops and Unilateral Hearing Loss

Last August, a post in this section described unusual findings in a patient with unilateral sensorineural hearing loss and retrocochlear findings who was referred for MRI to rule out acoustic neuroma. An acoustic neuroma is a benign, small, slow-growing tumor on the VIII cranial nerve–technically called a vestibular schwannoma.

The MRI found no evidence of a tumor but surprisingly identified a “vascular loop” occupying some of the space reserved for the VIII nerve to emerge from the inner ear and enter the brain. Vascular loops can mimic symptoms of acoustic neuroma and that’s the topic of today’s post.

The Story on Vascular Loops

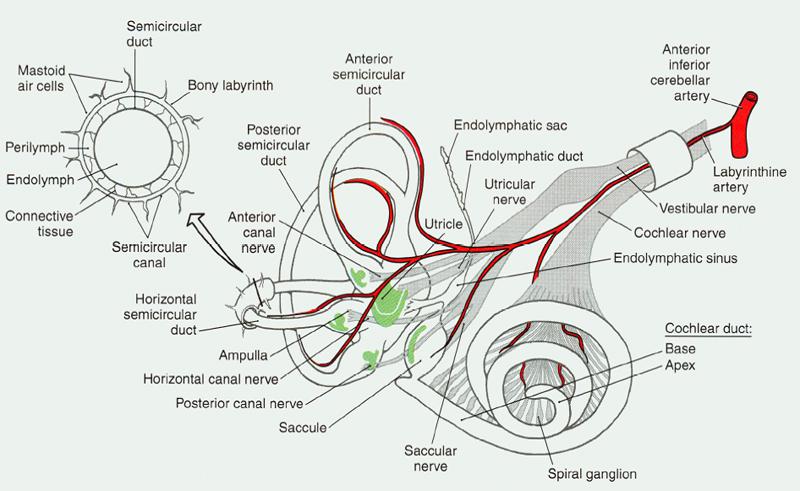

Figure 1. Blood supply to peripheral auditory-vestibular system.

Vascular loops are anatomical anomalies of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA). We mention that artery because it is the blood supply for the inner ear, which includes hearing and vestibular (balance) systems. Figure 1 shows the system with the blood supply shown in red.

Notice how it “shares” a narrow passage way with the vestibular and acoustic branches of the VIII cranial nerve. Without the VIII nerve, we do not hear. The result is the same if the blood supply is compromised due to injury, space occupying lesion, disease, or anatomical anomaly.

A Bottleneck

In Figure 1, the artery and two nerve branches appear wrapped in a little cylinder. That’s just a visual so you can see how they lie inside the skull. In actuality, all three pass through a short (about 1 mm) narrow little corridor (about 3.5 mm) that nature drilled into the temporal bone before entering the brain proper in what’s called the cerebellopontine angle (CPA).

The connecting corridor — called the internal auditory meatus — protects the blood and nerve supplies while linking the ear and vestibular system to the brain. That doesn’t leave much room for error or extras. Speaking of extras, the facial nerve also goes through that corridor, though it’s not shown in figure 1. Talk about a traffic jam! No room left at all now.

The Traffic Jam: Injuries But No Fatalities

Yet, into this bottleneck extra vascular AICA anomalies in the CPA can nudge and impose, “suspected of causing hearing loss, tinnitus, and vertigo” due to “the complex interaction between the vascular loop and eighth cranial nerve, in which the loop exerts pressure on the nerve, and the nerve compromises inner ear circulation.”

One study looked at 15 patients with unilateral (one-sided) or asymmetrical hearing loss and/or tinnitus who had imaging of the CPA suspected acoustic neuroma but were found to have vascular loops instead. Complete audiovestibular work-ups on those patients revealed:

- the already-established hearing loss on the side with the vascular loop

- good, symmetrical, word recognition performance in both ears

- spontaneous nystagmus (a vestibular sign) in 14 of the 15 subjects

- a low proportion (one-third) of subjects with abnormal calorics (a test of the vestibular system)

- no significant relationship between presence of tinnitus and presence or position of vascular loops vis-a-vis the auditory portion of the VIII nerve

The auditory findings of this study agreed with previous research by McDermott et al (2003) who reported a “clear” relationship between vascular loops and unilateral hearing loss, but not with tinnitus, in a prospective imaging study of over 300 patients with complaints of unilateral hearing loss and/or other “auditory symptoms.”

From these studies and others, Applebaum and Valvasorri (1985) arrived at the follow recommendation for practitioners:

Eighth nerve tumors and vascular loops produce similar symptoms, but a cochlear type of hearing loss with good speech discrimination and normal caloric testing should raise suspicion of a vascular loop.

Despite the suggested profile of “good, symmetrical word recognition scores,” the patient in last August’s post presented with poor speech discrimination on the involved side and almost 20% roll-over. Even more reason to get an MRI. Other studies associate vascular loop with unilateral pulsatile tinnitus accompanying same-ear hearing loss (Ramly et al., 2014). See Chadha and Weiner (2008) for a review of studies.

According to the reports in the literature, as well as the recommendations given in the aforementioned case study, surgery is rarely recommended for AICA loops. From the patient’s perspective, this is a good news/bad news conclusion: there is no tumor, but no treatment for the permanent unilateral hearing loss.

References

Applebaum & Valvasorri. Internal auditory canal vascular loops: audiometric and vestibular system findings. Am J Otol. 1985 Nov;Suppl:110-3.

Chadha NK & Weiner GM. Vascular loops causing otological symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Otolaryngol. 2008 Feb;33(1):5-11. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2007.01597.x.

McDermott et al. Anterior inferior cerebellar artery syndrome: fact or fiction. Clinical Otolaryngology & Allied Sciences. Volume 28, Issue 2, pages 75–80, April 2003.

Ramly NA et al. Vascular loop in the cerebellopontine angle causing pulsatile tinnitus and headache: a case report. EXCLI J. 2014; 13: 192–196. Published online 2014 Feb 27. PMCID: PMC4464511

image from study blue

Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss: a primer for patients and providers

Sudden hearing loss is one of the most disconcerting events in the lives of patients and audiology practices. As its name suggests, there is no warning nor is there any way to predict who is as risk. Typically, the audiologist meets the patient for the first time as the result of this sudden, potentially devastating event. There is no time to get to know one another.

The patient is terrified, probably has little if any knowledge of audiology, and enters the relationship is a decidedly defensive position. Unlike typical counseling and consultative selling that accompanies acquired hearing loss, the audiologist’s professional response in the case of sudden loss must be at once highly diagnostic, highly supportive, and immediate.

What to Do

In every case, a person who experiences sudden hearing loss needs to be seen by both an audiologist and an Ear-Nose-Throat (otolaryngologist) physician, preferably one who specializes in ears (otologist). Audiometric evaluation should be performed immediately, though the audiologist needs to exercise care in selecting which tests to perform from the standard battery, avoiding those that introduce extreme pressure (atmospheric and sound) into the ear canal.

The purpose of the hearing evaluation is two-fold: to measure how much hearing has been lost initially, and determine whether the sudden loss is due to malfunction of the hearing nerve or the middle ear. Hearing losses due to nerve damage are called “sensorineural;” those due to middle ear problems are “conductive.” Sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL) is a medical emergency.

As soon as the hearing loss is charted, the patient goes into the hands of the physician for assessment and a treatment plan. It is very important that serial audiograms are performed during the treatment and afterward, to determine whether recovery is present; also to determine whether post-medical treatment with amplification is in order, at which point the patient is handed back into the hands of the audiologist.

It is not possible to predict recovery time or degree of recovery. This is a time of great uncertainty for the patient as s/he waits and is handed back and forth between professions.

What Can Happen

In the past, different physicians and audiologists have used individualized approaches that depended on their experience, knowledge, and empathy. Not every audiologist has had much if any experience with sudden hearing loss. A provider with little or no exposure to SSNHL is not a good thing for the patient who experiences this traumatic event.

Alternatively, patients may end up in emergency rooms if this frightening event happens at a time which does not allow them quick access to hearing and ear specialists. ER physicians are not going to approach the problem by ordering an audiogram, if for no other reason than that audiologists are not part of the ER experience.

All of the above spells out why there is a need for standardization of protocols for handling patients who present with sudden hearing loss. In 2012, the American Academy of Otolaryngology published a Clinical Practice Guideline for Sudden Hearing Loss as a journal supplement. It is summarized here:

KEY POINTS IN THE GUIDELINE

Among the main recommendations in the guideline are:

Prompt and accurate diagnosis is important:

- Sensorineural (nerve) hearing loss should be distinguished clinically from conductive (mechanical) hearing loss.

- The diagnosis of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss (ISSNHL) is made when audiometry confirms a 30-dB hearing loss at three consecutive frequencies and no underlying condition can be identified by history or physical exam.

Unnecessary tests and treatments should be avoided:

- Routine head/brain CT scans, often ordered in the ER setting, are not helpful and expose the patient to ionizing radiation.

- Routine, non-targeted, laboratory testing is not recommended.

Initial therapy for ISSNHL may include corticosteroids.

Follow-up and counseling is important:

- Physicians should educate patients with ISSNHL about the natural history of the condition, the benefits and risks of medical interventions, and the limitations of existing evidence regarding efficacy.

- Physicians should obtain follow-up audiometry within six months of diagnosis for patients with ISSNHL.

- Physicians should counsel patients with incomplete hearing recovery about the possible benefits of amplification and hearing assistive technology and other supportive measures.

More on Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss (SSNHL)

Recently, we wrote about guidelines for working with patients who experience Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss (SSNHL). SSNHL is an often-devastating syndrome that takes its victim by surprise and all too often persists even after attempts at treatment.

The Audiologist-Patient relationship is fragile and fraught, in part because of patients’ fears and in part because of the limited scientific information the Audiologist can offer:

...the audiologist meets the patient for the first time as the result of this sudden, devastating event. There is no time to get to know one another. The patient is terrified, probably has little if any knowledge of audiology, and enters the relationship is a decidedly defensive position. Unlike typical counselling... that accompanies acquired hearing loss, the audiologist’s professional response in the case of sudden loss must be at once highly diagnostic and highly supportive.

Perhaps without exception, patients are concerned with two questions:

- What caused this?

- Will my hearing recover?

Audiologists’ ability to answer either question is limited: recovery is a wait-and-see proposition, as covered in our last post. As for causes, what is know is listed below. It is clear from this list that most cases of SSNHL cannot be causally linked but when the cause is known, the problem is not due solely to a problem in the inner ear. Another ref: https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/sudden-deafness

- 12.8%: systemic infections (e.g., meningitis, syphilis, or HIV infection)

- 4.7%: diseases of the ear (e.g., cholesteatoma)

- 4.2%: trauma (e.g., blast trauma, skull-base fracture)

- 2.8%: cardiovascular disease

- 2.2%: paraneoplastic involvement of the inner ear

Over 70% of SSNHL cases cannot be linked to a cause. These cases, called “Idiopathic Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss” (ISSNHL) are attributed to effects of unknown viral, vascular, or immunological disturbances.

SSNHL represents one of the few true emergency situations that Audiologists face in practice management. A good policy is to see the patient as soon as possible for diagnostic audiologic evaluation, using a test battery that does NOT include acoustic reflex or acoustic reflex decay testing, due to the fragile condition of the ear.

Weekly audiologic monitoring commences, along with adequate counseling time, until the otologist, audiologist, and patient feel that hearing has stabilized. Hearing aid(s) may be considered at that time, with the caution that acclimatization to amplification through the injured ear is a slow, unpredictable, and highly individual process.

Do We Hear What We Eat?

Large scale data from a number of epidemiological studies is yielding valuable insights into incidence and prevalence of hearing loss in different cohorts. As just one example, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) study data tells us that 93% of white men in the 60-69 age group have high frequency hearing loss and 43% have hearing loss in low and mid-frequencies. That is just a peek at all that this wealth of longitudinal data is beginning to reveal about hearing loss, gender, aging, and a plethora of other health-related variables.

In recent years, studies have begun to plumb the epidemiological data for lifestyle links to hearing loss. Exercise, social activities, work environments, and food choices are examples of lifestyle choices that could influence hearing health. Information on results of such research can be immediate importance to consumers and hearing healthcare providers, as well as other stakeholders, if is shown that improvements are possible as a part of daily life. As one study puts it:

“Diet is one of the few modifiable risk factors for age-related hearing loss.” (Gopinath et al 2011)

Antioxidants and vitamins, ingested via food or supplements, are obvious candidates for investigation. The data are mountainous and the challenge of controlling covariance among a large number of variables demands careful study design and statistical analyses. Different types of subjects in different numbers for different lengths of time comprise different data sets, which adds to the challenge. Finally, hearing evaluation measurements were not top in the minds of those who designed baseline measures when the studies were initiated decades ago.

As a result, the data may be (partially) in, but the results are just beginning to give us some idea of how or if vitamins and antioxidants are important to our hearing. Today’s and next week’s posts look at what has come out of the studies to date.

Quick Statistics Primer

It’s not surprising that complex study designs and analyses test our ability to understand their findings and conclusions. Most audiologists, in good company with most readers in general, do not have years of education in statistics. It’s easier to interpret study findings if you have a good handle on definitions and terms which are common to researchers but not so commonly bandied about in clinical practices.

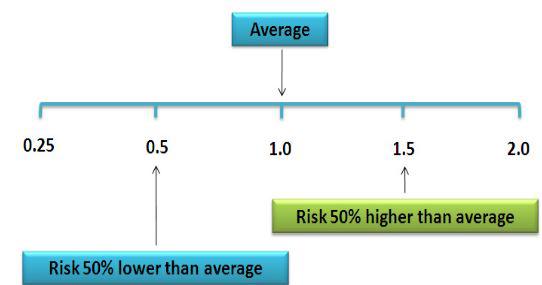

Figure 1. Relative Risk illustration (from nutridesk.com).

Here are a few reminders that may prove helpful in reading the summary studies in the next sections.

- Incidence: This is a proportion or percentage figure that is a measure of the risk of developing hearing loss in a time interval specified by the study.

- Prevalence: Another proportion or percentage, this figure states the portion of hearing loss in the study population at a given time.

- Odds Ratio (OR): This states the odds that hearing loss occurs with an intervention (i.e., vitamin intake) compared to the odds of it occurring without the intervention (i.e., no vitamin). An OR = 1 means the odds are even and the intervention has no effect. A positive OR means the risk is heightened by the intervention; a negative OR means the risk is lowered. NOTE: Hi or low odds do not state or imply causality.

- Risk Ratio (RR): Also called the Relative Risk. RR states the odds of hearing loss in one intervention group compared to other intervention groups over time. RR = 1 means even odds, same as OR.

- Hazard Ratio (HR): This is the same measure as RR but only at one point in time. HR is a measure of “instantaneous risk”, not cumulative risk over a time interval like OR and RR. Like OR and RR, HR = 1 means even odds.

- Confidence Level (CL): The calculated probability that any of the ratios above are true. It’s needed because all data come from samples of an entire population. Large samples are better for estimating than small samples, but even large samples contain some degree of uncertainty. A 95% CL means that there is a 95% probability that the HR, RR or OR is correctly reflecting the true population and is not in error.

- Confidence Interval (CI): The Confidence Interval (CI) states the upper and lower value of the estimate. When the CL is 95%, the CI extends from 2.5% to 97.5% of the measurements.

Three Studies of Hearing Loss and Dietary Risk Factors

Next week, we’ll compile some basic descriptors for the designs and findings of three important studies:

- Health Professionals Follow-up Study (Shargorodsky et al, 2010)

- Blue Mountains Hearing Study (Gopinath et al, 2011)

- Conservation of Hearing Study (Curhan et al, 2015)

Although the studies are monumental, they vary in scope, goals, length, etc., and each has limitations. But in the aggregate, they lend support to the idea that vitamin antioxidants have some influence on hearing loss which deserves further study.

References

Agrawal Y et al. Prevalence of hearing loss and differences by demographic characteristics among US adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2004. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1522–1530.

Curhan SG et al. Carotenoids, vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin E, and folate and risk of self-reported hearing loss in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015 Nov; 102(5): 1167–1175. Published online 2015 Sep 9. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.109314 PMCID: PMC4625586

Gopinath B et al. Dietary antioxidant intake is associated with the prevalence but not incidence of age-related hearing loss. J Nutr Health Aging 2011;15:896–900.

Shargorodsky J et al. A prospective study of vitamin intake and the risk of hearing loss in men. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010 Feb; 142(2): 231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.10.049 PMCID: PMC2853884 NIHMSID: NIHMS180764

A Compendium Of Research Studies And Reports On Aging And Hearing

|

Study |

Conclusions |

| Lin FR et al.Hearing loss and incident dementia Arch Neurol. 2011;68(2):214-220 | “Hearing loss is independently associated with incident all-cause dementia. Whether hearing loss is a marker for early-stage dementia or is actually a modifiable risk factor for dementia deserves further study.” |

| Lin FR, Thorpe R, Gordon-Salant S, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss prevalence and risk factors among older adults in the United States. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2011;66(5):582-590. | “Hearing loss is prevalent in nearly two thirds of adults aged 70 years and older in the U.S. population. Additional research is needed to determine the epidemiological and physiological basis for the protective effect of black race against hearing loss and to determine the role of hearing aids in those with a mild hearing loss.” |

| Goman AM & Lin FR. Prevalence of Hearing Loss by Severity in the United States.Am J Public Health. 2016 Oct;106(10):1820-2. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303299. Epub 2016 Aug 23. | "Hearing loss directly affects 23% of Americans aged 12 years or older. The majority of these individuals have mild hearing loss; however, moderate loss is more prevalent than mild loss among individuals aged 80 years or older.” |

| Mamo SK et al. Prevalence of Untreated Hearing Loss by Income among Older Adults in the United States. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(4):1812-1818. | "Overall, approximately 20 million Americans 60 years or older have an untreated clinically significant hearing loss.” |

| Deal JA et al. Hearing Impairment and Incident Dementia and Cognitive Decline in Older Adults: The Health ABC Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016 Apr 12. pii: glw069. [Epub ahead of print] | "Hearing Impairment is associated with increased risk of developing dementia in older adults. Randomized trials are needed to determine whether treatment of hearing loss could postpone dementia onset in older adults.” |

| Mamo SK et al. Hearing Care Intervention for Persons with Dementia: A Pilot Study Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017 Jan;25(1):91-101. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.08.019. Epub 2016 Sep 22 | "Improved communication has the potential to reduce symptom burden and improve quality of life.” |

| Nirmalasari O et al. Age-related hearing loss in older adults with cognitive impairment. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017 Jan;29(1):115-121. doi: 10.1017/S1041610216001459. Epub 2016 Sep 22. | “Hearing loss is highly prevalent among older adults with cognitive impairment. Despite high prevalence of hearing loss, hearing aid utilization remains low.” |

| Kim MB et al.Diabetes mellitus and the incidence of hearing loss: a cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2016 Nov 6. pii: dyw243. [Epub ahead of print] | “In this large cohort study of young and middle-aged men and women, DM was associated with the development of bilateral hearing loss. DM patients have a moderately increased risk of future hearing loss.” |

| Contrera KJ et al. Association of Hearing Impairment and Anxiety in Older Adults. J Aging Health. 2016 Feb 24. pii: 0898264316634571. [Epub ahead of print] | “Hearing impairment is independently associated with greater odds of anxiety symptoms in older adults.” |

| Contrera KJ et al. Change in loneliness after intervention with cochlear implants or hearing aids. 2017: Laryngoscope Jan 6. doi: 10.1002/lary.26424. [Epub ahead of print] | Treatment of hearing loss with CIs results in a significant reduction in loneliness symptoms. This improvement was not observed with HAs. We observed differential effects of treatment depending on the baseline loneliness score, with the greatest improvements observed in individuals with the most loneliness symptoms at baseline. |

| Edwards JD et al. Association of Hearing Impairment and Subsequent Driving Mobility in Older Adults. Gerontologist. 2016 Feb 25. pii: gnw009. [Epub ahead of print | "Although prior research indicates older adults with HI may be at higher risk for crashes, they may not modify driving over time. Further exploration of this issue is required to optimize efforts to improve driving safety and mobility among older adults.” |