Breaking the Vicious Circles that Perpetuate Negative Attitudes Towards Hearing Care

Vicious Circles in Hearing Care

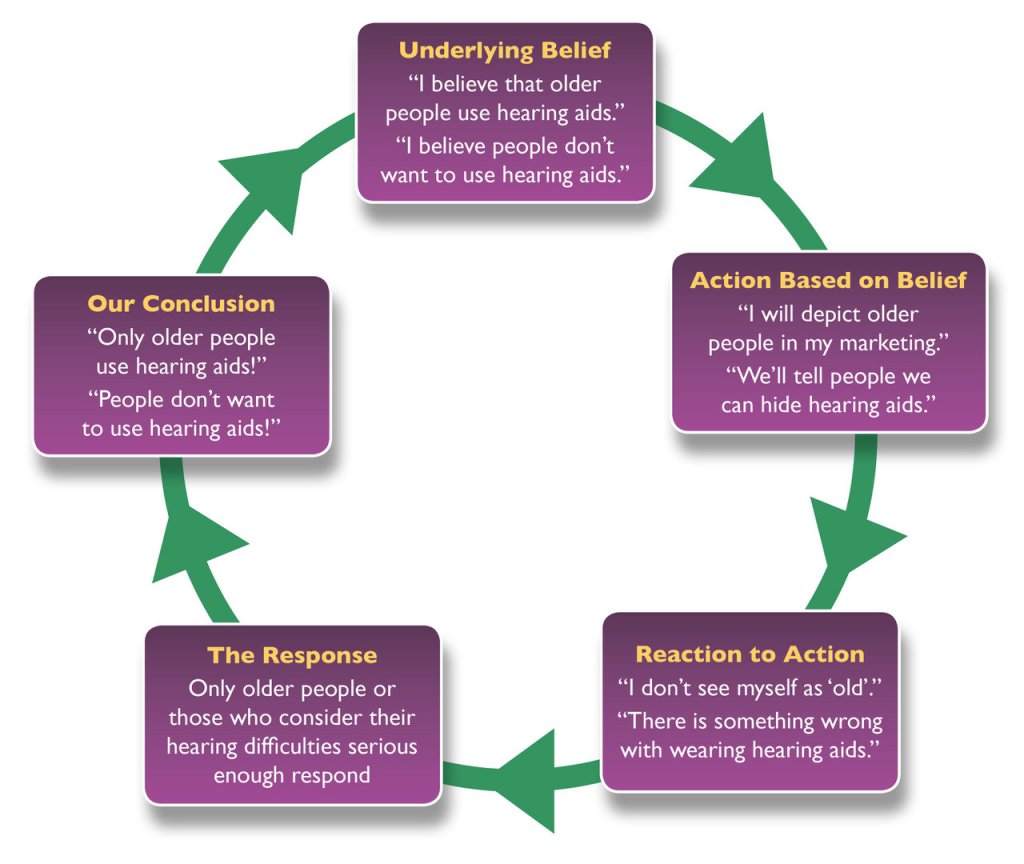

Hearing care is full of vicious circles. Take for example the widely held assumption within our field that people don’t want to be seen wearing hearing technology. Believing this we develop hearing solutions designed to be hidden, proudly proclaiming that “Nobody need know you’re wearing it.”

But consider the thoughts and feelings that such a message triggers in someone who encounters our message for the first time. At this stage they may have had no pre-conceived ideas about hearing care. Yet they gather from us in that one message that wearing hearing technology is something shameful. For why else would we suggest people want to keep it hidden? Out of all the positive messages we could have focused on, we instead chose a negative one.

After many years avoiding something that even “the experts” seem to consider shameful, our audience might eventually make it through our doors. What do they request? One of those tiny hearing devices that’s completely hidden—because that’s what our messages have been telling them to want, and their imagination has created the “backstory” for why it needs to be hidden. “See,” we tell ourselves. “We were right all along! People don’t want to be seen wearing hearing aids!”

And so the vicious circle begins all over again. Our original assumption is reinforced, and we succeed in perpetuating our outdated myths, fearful that if we do anything differently we will stop people coming through our doors. Meanwhile we hone our counselling skills as we try to persuade people to “accept” something that we’ve previously suggested was shameful. It’s easy to wonder if a significant proportion of our so-called rehabilitation is only necessary to counteract the negative messages we have propagated in the first place.

Figure 1. Examples of how the profession’s own underlying beliefs create vicious circles that perpetuate the original belief.

When we ask ourselves why so many people don’t want to be seen wearing hearing aids, we lazily blame it on the “s” word, treating it like some mythical beast that’s destined to oppose the efforts of the profession at every turn. We never think to question its reality; instead we simply act as if our beliefs about it are true, and our consequent actions give it credence.1,2

The same vicious circles are found in the stereotypes we use to market to an older, retired demographic. In doing so we signal to younger people of working age that hearing care is not for them, seeing their lack of response to our marketing as evidence that we were right to depict an older demographic, but which in turn creates a strong association in people’s minds of hearing aids with “growing old.” Yet still we fail to recognize our own role in maintaining this pernicious belief. Surely hearing technology should be associated in people’s minds with hearing as well as possible, of getting the most out of life! Yet by making hearing aids “an age thing” we make them a symbol of mortality3, then wonder why people wait so long4,5 before responding to our messages.

Breaking the Vicious Circles

Vicious circles are self-perpetuating, which means that hearing care will always be stuck with an older demographic who wait years before taking action and who resist hearing technology—because that’s what we continue telling society to do. If we want this to change, it is up to us to break the vicious circles we have trapped ourselves in. Otherwise we only have ourselves to blame. Society is supposed to take its lead from the experts,6 not the other way around.

To break these vicious circles we require a better set of tools to help us identify where people’s attitudes to hearing are coming from. It’s both naïve and vain to keep blaming things on “stigma” as if it’s some inescapable force we must all accept. Such generic labelling tells us nothing about what people’s internal thoughts and feelings7 are, nor how they got there, nor why they result in a desire to avoid hearing care. Unless we’re more specific we have nothing useful to work with.

Therefore, to change society’s attitudes we must be able to:

- Identify the things we are currently doing/saying that create/reinforce negative attitudes.

- Identify the things we should be doing/saying instead that will foster positive attitudes.8,9

The KLEAR Model for Understanding Attitudes to Hearing

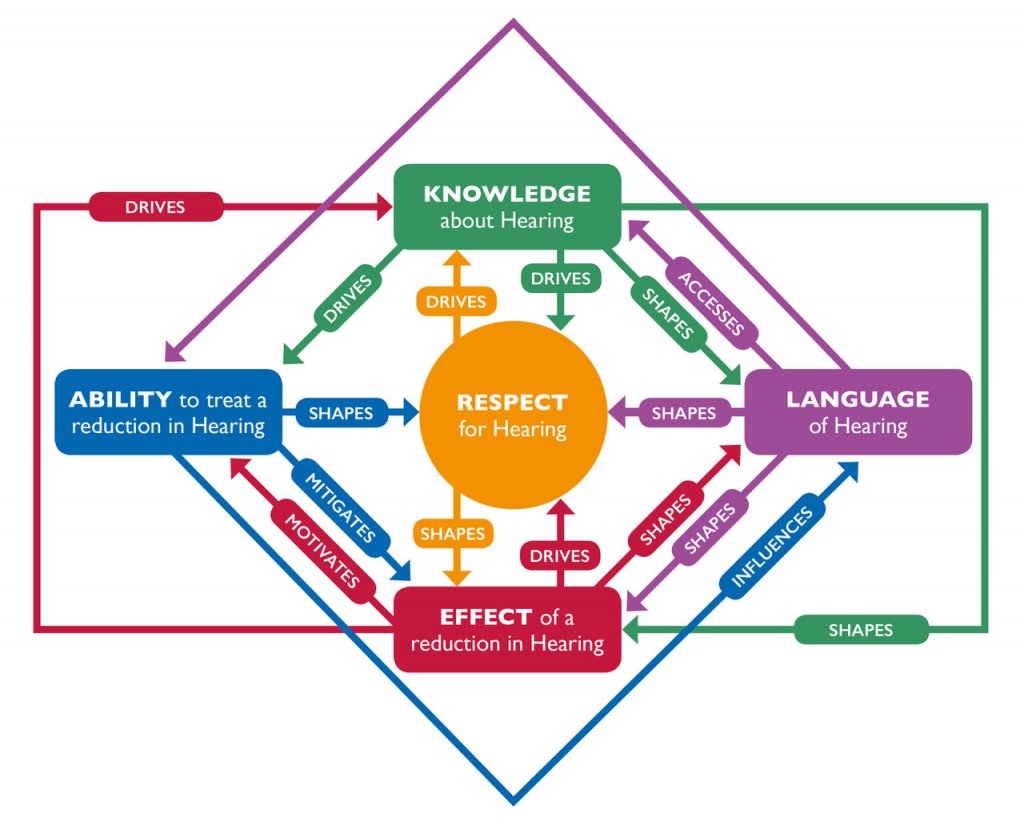

I would therefore like to introduce you to a model I developed called “The Five Key Drivers of Attitudes to Hearing,” summed up with the acronym KLEAR. It stands for:

- Knowledge (about Hearing) – what an individual, society or the profession knows.

- Language (of Hearing) – the words we use to talk about matters relating to hearing.

- Effect (of a reduction in Hearing) – how a reduced hearing capacity affects the individual, those they encounter and wider society.

- Ability (to treat a reduction in Hearing) – the interventions we have available to mitigate the effect of a reduction in hearing.

- Respect (for Hearing) – how someone regards their hearing and the resulting behaviour.

The diagram in Figure 1 illustrates how these five drivers interact with one another.

Figure 2. KLEAR – the Five Key Drivers of Attitudes to Hearing, and how they relate to one another.

For the purposes of this article in addressing hearing care’s vicious circles, we’re going to focus on the first driver: Knowledge. However, we should bear in mind that the five key drivers are interrelated. For example, we’ve already touched on how the word ‘stigma’ (Language) is too generic to properly access someone’s thoughts and feelings (Knowledge) about hearing, how it shapes disliking for hearing care (Respect), and how it intensifies the psychosocial impact (Effect) of having a reduction in hearing.

How the Knowledge Driver Works

What we know about something shapes our thoughts and feelings, and ultimately our behaviour. Sometimes what we “know” is not necessarily true or accurate. I may “know” that the earth is flat, and be so convinced of this “fact” that I will passionately argue with anyone who suggests otherwise, and you’d never be able to convince me to sail beyond the horizon. In the 21st century such “knowledge” seems risible because we have so much evidence to the contrary, not least because we can book ourselves a world cruise.

This example illustrates seven principles for how knowledge drives attitudes:

- Knowledge can be true or false, but people will feel and act as if it’s true if they believe it.10

- When we look at people’s actions it reveals something of their underlying knowledge.12 This applies to our own actions too.13

- As society’s knowledge moves towards accuracy or evidential truth, outdated myths get dispelled, and newer generations are more likely to adopt the updated knowledge.

- New knowledge normally begins as the property of the few who discover it. It will remain there unless there is a mechanism for dissemination.

- If that knowledge is important enough, relevant enough and accessible enough, ownership of the knowledge will transfer from the few to the many, becoming “common knowledge.”

- If we change someone’s underlying knowledge (e.g., through education), we can change the accompanying feelings and actions.

- Sometimes the way to change someone’s knowledge is to change their behaviour13 and infer their knowledge from their own actions.

The same 7 principles apply to people’s knowledge about hearing. If we personally know that intense noise permanently damages hearing (1), we have a greater chance of protecting our hearing than if we didn’t know (2). If enough of the right individuals in society know, that collective knowledge will drive legislation and public advice (6) regarding health and safety (7), and dispel outdated myths such as “only the weak need protect their hearing” (3), eventually becoming common knowledge (5).

Conversely, if our knowledge about hearing is erroneous or outdated, our thoughts and feelings are more likely to result in inappropriate action. We might ‘know’ that “only old people have hearing problems.” This “knowledge” may be assembled from our memory of an older relative who used hearing aids when we were younger, from comedies making fun of older people who can’t hear, from the imagery used by hearing care professionals and hearing aid manufacturers. So if we do not perceive ourselves as being old14–16 then we’re far less likely to accept that we have a problem with our own hearing, and consequently we’re less likely to use hearing technology.16

Applying the Knowledge Driver to Hearing Care

If people are avoiding hearing care, or are reluctant to use hearing technology, the first thing we should be asking ourselves is, what do they “know” about hearing that is leading to this behaviour? The second question to ask is, what knowledge do they need instead?

The Effort of Acquiring New Knowledge

Acquiring new knowledge requires effort,17,18 especially if it runs counter to what a person already knows. Not only do they have to seek out and digest the relevant information if it’s not easily accessible to them, but they have to make it fit with their existing knowledge.19,20

If someone tells me the world is round, I’m going to recall all the maps drawn by “experts” over successive generations that show me it’s flat; I will remember the scary tales from my childhood of adventurers who sailed too far; I will consider the visual flatness of the horizon; I will think about my friends and family who also know it’s flat. This “new knowledge” has to compete with these well-established “facts” in my mind before you’ll convince me to sail over the edge of the earth.

It would have been so much easier if someone had introduced this new knowledge to me before I’d already mind up my mind. Perhaps as part of the school curriculum, when I was still trying to figure the world out21 (and yes there is a strong case for hearing education in schools). But as adults we already “know” how the world works. A lifetime of experience has established templates in our minds that speed up our processing of new information. That means a lot of our adult thinking is carried out unconsciously using schemata,22 heuristics, and stereotypes.23 To override this automatic processing we need to consider something to be important enough or relevant enough to deserve our conscious, effortful thought.17

How, then, do we utilize this driver of Knowledge to change people’s attitudes to hearing? That depends on how relevant or important hearing care is to a person.

Making New Knowledge Accessible

Think of a see-saw. On one side, we have “personal relevance” and “importance.” On the other side, we have “accessibility”, i.e. how little effort it takes to acquire the knowledge. The less important or relevant someone considers hearing care to be, the more accessible we have to make the knowledge for them. It’s a bit like a parent chopping up food into pieces for a small child to eat. We know they’re either unable or unwilling to put the effort in themselves, so we position it right in front of them and make it easy for them to pick up, to swallow and to digest.

This is what advertisers and politicians do: they find a way to condense “knowledge” into an easy-to-remember, easy-to-apply message24 which they repeat25 until it becomes “common knowledge.” What they’re doing is tapping into our automatic processing: if we believe that everyone seems to know something, we assume it’s what we’re expected to know too (“If in doubt, follow the crowd”26). Furthermore, because the message is easy to recall, it increases “fluency,” the feeling of ease associated with mental processes. People subconsciously assume that because there’s less mental effort involved, fluent messages are “more true,” “more likeable,” and “come from a more intelligent source.”28 Advertisers and politicians use this to their advantage; how much more should healthcare professionals?

This is the principle behind repeating messages like: “Eyes checked. Teeth checked. Hearing checked?”

Figure 3. “Eyes checked. Teeth checked. Hearing checked?”

It’s a simple message that the majority can relate to because it builds on existing “common knowledge” that it’s sensible to have our eyes and teeth checked regularly throughout life. By associating hearing checks with routine health behaviour like this, we’re repositioning hearing care as a normal, mainstream activity for people who take good care of their health. We’re no longer suggesting that hearing care is for when “you’re old enough, deaf enough, or desperate enough”. So not only do we avoid stigmatising those who already benefit from our services—as we do whenever our messages highlight someone’s deficiencies—we’re also casting our net of relevance much, much wider. We now take in all those individuals who in the past may have waited years5 before taking action because they didn’t consider themselves to be “ready.”

Making New Knowledge Relevant and Important

We now turn to the other side of our knowledge see-saw: relevance and importance. If we can establish in people’s minds why hearing care is relevant to them, and why it’s important to have hearing checked routinely, and why we shouldn’t hesitate to use hearing technology, then we motivate people to seek out our services rather than avoid them. We just have to ensure that people then have available opportunities to act on that motivation.29,30,31

But motivation is where our traditional approach to hearing care falls down. Think about it: we try to persuade people to have a test we want them to fail, to find out if they’re ‘suffering’ with a condition they do not personally notice,32 and to accept a treatment that will not cure them and for which they perceive no need.33 And, as if that wasn’t a hard enough sell, we often require them to invest significant sums of their own money to do so.

What in our rational collective mind convinces us this could be anything but a defective strategy doomed to deter more people than it attracts? Why do we believe such approach could ever motivate people? Could it be that we too have been guilty of our own faulty “knowledge,” which has been determining our own actions all these years? Could it be that we’ve been believing the world is flat, when really, it’s round?

When we make hearing care about having a condition we immediately exclude all those who believe their hearing is “good enough” or who do not believe that the seriousness of the condition outweighs the perceived costs—social, psychological, economic—of the treatment.34 Historically our approach has been to discredit a person’s perceived hearing ability (“You have a moderate hearing loss that you’ll never get back”); or to increase the perceived seriousness of the condition by linking it to other ‘more serious’ conditions, like dementia35 or depression36; or to reduce the perceived costs of the treatment by making it hidden or using promotional offers. But such attempts are only effective if someone already considers themselves “old enough, deaf enough or desperate enough” for our messages to be relevant, otherwise they won’t even notice them, let alone respond.37,38

We have been approaching this backwards.

Shifting from ‘Condition-Based’ to ‘Hearing-Based’ Knowledge

Instead of focusing on ‘hearing impairment’ and ‘deafness’ as the basis for our knowledge, we need to shift our frame to ‘hearing’. Immediately we do so, things begin falling into place.

Firstly, our relevance expands from around 2.5%43 of the population to well over 99%.44 This instantly increases the audience size that’s paying attention to our messages, gathering up many of the people who had previously seen hearing care as irrelevant.

Secondly, instead of always having to talk up the negatives of having a hearing loss, we begin talking about the positives of hearing—and the advantages this incredible sense bestows upon us through language and music.

We talk about how hearing connects our brains 24/7 to the world around us; to the minds and hearts of other humans in real time; to the opportunities and serendipities of being in the right place at the right time. We can talk about how indispensable hearing is for maintaining the flow of conversation and the spontaneous transfer of information, and how our dependence on speech makes hearing integral to relationships, education, personal development, collaboration, effectiveness at work, the economy, government, entertainment and more.

These facts are so blindingly obvious, they’ve simply been taken for granted. Like Hans Christian Anderson’s The Emperor’s New Clothes, it’s just waiting for someone like us to point out what the crowd already knows to be true. The knowledge is already there.

The wisdom of maximizing and maintaining ‘our social sense’ throughout life now becomes immediately apparent. Routine hearing checks become about ensuring we continue to hear as others expect; hearing technology becomes the means to maintain our brain’s 24/7 connection to world outside our own heads; hearing protection prevents us corroding one of our most valuable resources.

By switching our frame from “hearing loss as a condition” to “hearing as a resource” we suddenly find ourselves in possession of one of society’s most important roles: Guardians of Hearing, empowering individuals and society to reach and maintain their full potential through maximal hearing.

Changing the Symbolism to Alter Behaviour

We began this article discussing how our messages have often been about hiding hearing technology. What we failed to understand was that people haven’t been trying to hide the product; they’ve been trying to hide what that product symbolizes.41

That symbolism has arisen from outdated knowledge based on “hearing loss as a condition”42 and our own vicious circles repeatedly associating our product with the condition. But now, by specifically targeting the Knowledge driver, we’ve changed the meaning of the symbol. Hearing technology becomes associated with staying connected and maximizing human potential—a symbol that says something positive to society about the user of the product. It’s therefore no longer something people feel the need to avoid or hide. By changing the meaning, we’ve changed people’s behaviour.

Disseminating our New Knowledge

Our new knowledge is not going spread automatically simply because we’ve read it in an article. We have to make it happen. That doesn’t mean extra expenditure on mass marketing; it just requires us to change the way we present our current messages43 and how we talk to our patients or clients. Each person we encounter, or who comes into contact with our current marketing, is a fresh start and a chance to impart our new knowledge. They in turn will spread it to their friends and family providing we make it contagious44 enough.

Here, then, are some guidelines for getting the new knowledge out there:

- Don’t automatically assume that people want to avoid hearing care or dislike hearing technology. If you do, you inadvertently transfer your own outdated knowledge into their thinking. Many people are likely to have a neutral attitude. Don’t be the one to poison it!

- Use your pre-appointment messages and marketing (e.g., website) to expose people to knowledge based on maximal hearing and listening.45 This will prepare the ground before they come through your door and help direct your conversations towards ‘maintaining potential’ rather than ‘losing health’. Show people of all ages making use of their hearing across the spectrum of listening situations, and don’t embarrass someone who looks at your website or marketing in front of others. In other words, don’t use material that suggests your audience considers themselves “old, deaf, or desperate.”

- Redirect outdated knowledge as you come across it. You’re bound to encounter people who say things like, “I don’t want to be seen as being old” or “There’s still a stigma…” Part of your role as a Guardian of Hearing is to re-educate them. So, become a master of gently catching such statements and correcting them without causing offence. For example, you might begin your reply with: “I think that may have been true in the past…” This gently reframes their knowledge as outdated. You can now update them with the new knowledge like this: “But now that we know more about how hearing works, and how important it is to keep our brain stimulated throughout life, people are realizing that it’s all about hearing as well as possible. That’s why today’s hearing technology is…”

Summary

In this article we have looked at how a person’s knowledge provides the ingredients for their attitudes, which in turn determines their behaviour. If someone’s underlying knowledge is flawed, their attitudes will be too, which will be evident from their behaviour. Hearing care has found itself trapped in vicious circles that perpetuate outdated ideas, resulting in people avoiding hearing care. To break these vicious circles, we need to replace people’s outdated knowledge with a new knowledge more likely to result in a positive attitude and behaviour. We can do this by shifting our frame from “hearing loss as a condition” to “hearing as a resource” and making the purpose of hearing care to help individuals and society “maintain their full potential through maximal hearing”. We finished with examples of how we can disseminate this new knowledge without the need for additional expenditure.

References

- Merton RK. The self-fulfilling prophecy. Antioch Rev 1948;8(2):193–210.

- Alcock CJ. The Power of Self-Fulfilling Prophecies. Hear Profess 2014;63(3):13–19.

- Greenberg J, Schimel J, and Martens A, 2002. Ageism: Denying the face of the future. Ageism: Stereotyping and prejudice against older persons. MIT Press; 2002.

- Kite ME and Wagner LS. Attitudes toward older adults. Ageism: Stereotyping and prejudice against older persons. MIT Press; 2002.

- Kochkin S. MarkeTrak VIII: 25-year trends in the hearing health market. Hear Rev 2009;16(11):12–31.

- Cialdini RB. Harnessing the science of persuasion. Harvard Bus Rev 2001;79(9):72–81.

- Eagly AH and Chaiken S. Attitude structure and function. 1998.

- Petty R and Cacioppo J. Communication and persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to attitude change. Springer Science & Business Media; 1989.

- Perloff RM. The dynamics of persuasion: communication and attitudes in the twenty-first century. Routledge; 2010.

- For a fascinating example of this see Festinger L and Schachter S. 2013. When prophecy fails. Simon and Schuster.

- Malle BF. Attribution theories: How people make sense of behavior. Theor Soc Psychol 2011;72–95.

- Bem DJ. Self-perception theory. Adv Exper Soc Psychol 1972;6:1–62.

- Cooper J and Scher SJ. Actions and attitudes: The role of responsibility and aversive consequences in persuasion. The psychology of persuasion, pp.95-111; 1994.

- Rubin DC and Berntsen D. People over forty feel 20% younger than their age: Subjective age across the lifespan. Psychonom Bull Rev 2006;13(5):776–80.

- Weiss D. and Lang FR. “They” are old but “I” feel younger: Age-group dissociation as a self-protective strategy in old age. Psychol Aging 2012;27(1):153.

- Wallhagen MI. The stigma of hearing loss. Gerontologist 2010;50(1):66–75.

- Petty RE and Cacioppo JT. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In: Communication and persuasion. Springer New York; 1986.

- Chaiken S and Eagly AH. Heuristic and systematic information processing within and. Unintended thought 1989;212:212–52.

- Eagly AH and Chaiken S. Attitude strength, attitude structure, and resistance to change. Attitude strength: Anteced Consequenc 1995;4:413–32.

- Petty RE. Briñol P, and DeMarree KG. The Meta–Cognitive model (MCM) of attitudes: Implications for attitude measurement, change, and strength. Social Cognition 2007; 25(5):657–86.

- Visser PS and Krosnick JA. Development of attitude strength over the life cycle: surge and decline. J Personal Soc Psychol 1998;75(6):1389.

- Axelrod R. Schema theory: An information processing model of perception and cognition. Amer Pol Sci Rev 1973;67(04):1248–66.

- Fiske ST and Taylor SE. Social cognition: From brains to culture. Sage. See chapters 7, 8 and 11; 2013.

- Heath C and Heath D. Made to stick: Why some ideas take hold and others come unstuck. Random House; 2008.

- Sawyer AG. Repetition, cognitive responses, and persuasion. Cognit Resp Persuas 1981;237–61.

- Cialdini RB. Science and practice. Chapter 4; 2009.

- Shah AK and Oppenheimer DM. Heuristics made easy: an effort-reduction framework. Psycholog Bull 2008;134(2):207.

- Oppenheimer DM. The secret life of fluency. Trend Cognit Sci 2008;12(6):237–41.

- Ajzen I. Theory of planned behavior. Handb Theor Soc Psychol 2011;1(2011):438.

- Fishbein M. A theory of reasoned action: some applications and implications; 1979.

- Fazio RH and Towles-Schwen T. The MODE model of attitude-behavior processes. Dual-process theories in social psychology.97–116; 1999.

- Alcock C. It’s not denial. It’s observation. Hear Rev 2015;22(12):16.

- Kochkin S. MarkeTrak VII: Obstacles to adult non‐user adoption of hearing aids. Hear J 2007;60(4):24–51.

- Champion VL and Skinner CS. The health belief model. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice 2008; 4:45–65.

- Lin Frank R. Hearing loss in older adults: who's listening? JAMA 2012;307.11:1147–48.

- Li, Chuan-Ming, et al. Hearing impairment associated with depression in US adults, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005-2010. JAMA Otolaryngol–Head Neck Surg 2014;140.4:293–302.

- Roser C. Involvement, attention, and perceptions of message relevance in the response to persuasive appeals. Communicat Res 1990;17(5):571–600.

- Lee K, Hakkyun K, and Vohs KD. Stereotype threat in the marketplace: consumer anxiety and purchase intentions. J Consumer Res

- Based on approximately 1 in 10 people recognising a problem with their hearing (10%), and 1 in 4 (25% of 10%) of those taking action. See Kochkin S. MarkeTrak VIII: 25-year trends in the hearing health market. Hear Rev 2009;16(11):12–31.

- No official figures exist for the number of people who use a visual language (e.g. American Sign Language), but it is very small as a percentage of a population. For example, estimates for ASL in the US seem to be around 250,000 to 500,000 users, which is less the 0.2% of the population. The remainder therefore, over 99%, use an oral—aural language. See Mitchell, R.E., Young, T.A., Bachleda, B. and Karchmer, M.A., 2006. How many people use ASL in the United States? Why estimates need updating. Sign Language Studies, 6(3), pp.306-335.

- Solomon MR. The role of products as social stimuli: A symbolic interactionism perspective. J Consum Res 1983;10(3):319–29.

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Simon and Schuster; 2009.

- Alcock CJ. The 4 Questions: A framework for creating a new social norm for hearing.” Available at: http://www.audira.info/4Q.

- Berger J. Contagious: Why things catch on. Simon and Schuster; 2016.

- Beck DL and Alcock CJ. Right product. Wrong message. Hear Rev 2014;21(4):16–20.