Other People’s Ideas

Other People's Ideas

Calvin Staples, MSc, will be selecting some of the more interesting blogs from HearingHealthMatters.org which now has almost a half a million hits each month. This blog is the most well read and best respected in the hearing health care industry and Calvin will make a regular selection of some of the best entries for his column, Other People’s Ideas.

I recently fit my first pair of wearable hearing devices. It was a failure when compared to his current hearing aids. The patient had reviewed this product online, determined it was an excellent opportunity for him to try. He purchased the devices and brought them to me to help me guide him through the fitting and to see how they compared to his current hearing aid settings. He returned the devices after three unsuccessful weeks of use. I am sure there are wonderful non-traditional hearing aids available, but unfortunately this first experience was not what was expected. The following blogs and updates are related to PSAPs and OTCs as they will inevitably be part of our marketplace - Happy Reading!

Oticon OTC Hearing Aids? William Demant Says It May Make OTC Devices if US Demand Develops

By HHTM. Originally posted August 14, 2017. Reprinted with permission.

William Demant Holdings, one of the world’s largest hearing aid manufacturers, said it could start producing less expensive Over-The-Counter (OTC) hearing aids for the U.S. market if demand increases after the OTC legislation goes into effect. North America represents the largest and most lucrative market for Demant, the parent company to well-known hearing aid brand Oticon.

Shares of Demant, GN Store Nord and Amplify all fell earlier this month on news that the U.S. Senate voted to pass the OTC hearing aid legislation as part of the FDA Reauthorization bill.

Demant Keeping its Eye on OTC Hearing Aids

While the OTC legislation still needs to be approved and signed by President Trump, it is expected to be signed into law this year. Once the bill is signed into law, the FDA has up to three years to complete the rules and regulations surrounding OTC devices.

“I do not expect any significant change in the U.S. market, but should sales of products like these become substantial … we will produce some as well,”

–Soren Nielsen, CEO of William Demant

While Demant is the first major hearing aid organization to comment publicly on possible plans to produce OTC devices, it’s likely a safe bet to assume other major industry players already have plans to ensure they do not lose significant marketshare in North America in the coming years as the hearing aid market faces continued pressure from the consumer electronics industry.

Source: Reuters

Categorization of PSAPs?

Originally posted August 8, 2017. Reprinted with permission.

This post is a continuation of two previous posts relating to a proposed PSAP “Standard” (OTC Hearing Aid Standard, and PSAP Standard Review). This post relates to a section of the proposed “Standard” relating to the “categorization of PSAPs” (personal sound amplification products).1

Categorization – Criteria for Standardization

It is not clear what the purpose is for categories of device performance. Is the intent that a PSAP would have different levels of performance and labeled as Category 1, Category 2, or Category 3? Is a PSAP a PSAP or not? This suggests different levels for PSAPs. Since there is no such categorization of hearing aids, then why for PSAPs? With these thoughts in mind, the following is a continuation of attempting to determine what the various parts of the “Standard” relate to, and how they may or may not be significant.

Category I

This category is proposed to provide an acceptable range or threshold for the measurement made. Acceptable to who – the consumer or to those writing the” Standard?” On what basis is acceptability determined? It is possible that a $29 unit may be just as acceptable to one person as a $3000 unit is to another person? In speaking to a friend the other day, he commented that his dad purchased a $29 unit to help his hearing. I asked how he was doing, and was he satisfied? I was told that he is doing acceptably well, and that he was pleased with his purchase. Just because a measurement meets the “Standard” says nothing about how acceptable a product is to the consumer. Meeting or failing a single feature reminds one of something J. Donald Harris wrote about many years ago (paraphrased): just because you can find a single parameter statistically significant when viewed in isolation, it may have no significance when all parameters are combined.

Frequency Response Bandwidth

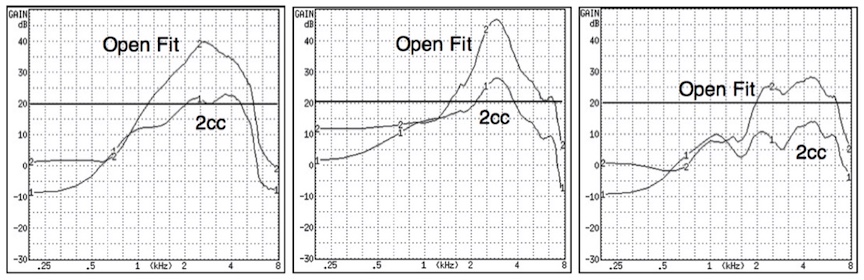

Figure 1. Three different premium-priced hearing aids measured using a 2cc coupler and an open fit coupler (Frye Electronics open coupler). How does making the measurement of a PSAP having an open fit on a 2cc coupler aid the consumer, since the responses (including the bandwidth), will be substantially different?

How does a frequency response allow a consumer a means to compare and evaluate competing systems? The same response fitted with an open or closed dome (Figure 1) provides different end user real-ear listening experiences. Even premium-priced hearing aids do not provide this real-ear information to the consumer. It is suspected that few hearing aid or PSAP consumers even know what a frequency response curve is, or what it actually represents. The “Standard” calls for measurements to be made into a 2cc coupler. However, many PSAP instruments are sold only with an open fitting, not a closed fitting, as is measured in a 2cc coupler. Therefore, it is confusing as to why they would be measured with a closed coupler, and then this information provided to a consumer, when it has nothing to do with the actual frequency response representation.

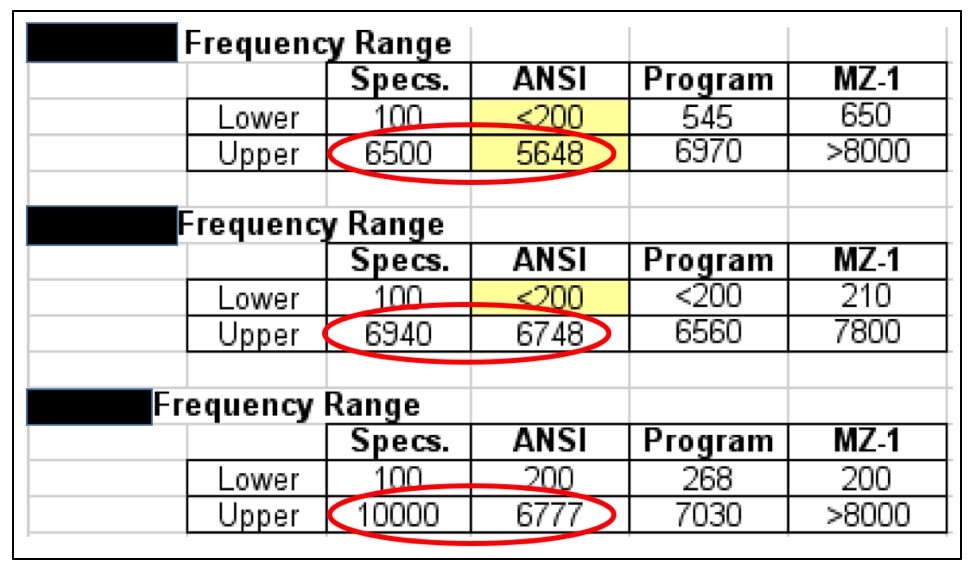

Figure 2. Three premium hearing aid manufacturers’ published frequency response lower and upper limits, and actual measured responses (measured in 2016). None met the upper limit, which most would agree is a more significant number than the lower limit. The “Program” is the measured response after each was programmed to the same hearing thresholds. The MZ-1 is a modified Zwislocki coupler measurement.

If truth in advertising, especially with respect to the frequency range is so important, current premium-priced hearing aids (among the Big Six) are not held to standards, as shown in Figure 2. All of these instruments failed to meet their published specifications, as measured using the ANSI test measurement Standard. It appears that PSAPs are going to be held to a higher standard.

What is magical or practical with having a low frequency cut off to extend to 250 Hz or lower? Many currently-fitted hearing aids do not go that low. In fact, most do not want amplification to go that low because this would amplify low-frequency background noise. This gives the appearance of being an intended built-in failure feature for a PSAP, especially since most PSAPs are fitted with an open/vented tip, which means that amplification at frequencies this low has been acoustically removed.

Frequency Response Smoothness

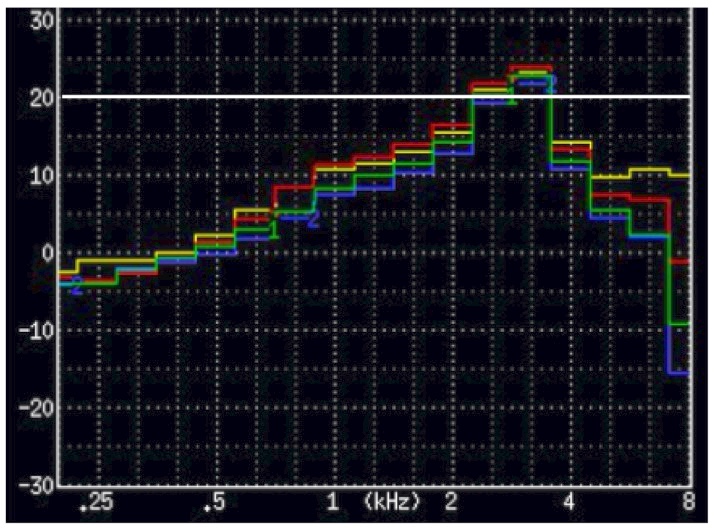

Figure 3. A premium hearing aid measured using 1/3 octave bands. The peak is 13 dB higher than the 2 lower-and higher 1/3 octave band measurements (they average 12 dB). This instrument would not qualify as a PSAP. Granted, this was not measured in a diffuse field (measured in a Frye 8000 Hearing aid test chamber) and used the ISTS test signal, but the unusualness of this smoothness requirement is curious.

Figure 3 shows 1/3 octave band measurements of a very popular current premium-priced hearing aid. According to the smoothness requirement, it would fail.

Maximum Acoustic Output

This is not the same as for hearing aids (for protection, they use 132 dB). Actually, isn’t this level a maximum performance standard to avoid uncomfortably loud sounds, rather than a minimum, as specified?

Distortion Control Limits

Measurement is a hearing aid standard. Does anyone know what a maximum criterion for distortion is, and how does it provide a minimum performance standard? Wouldn’t this be nice to know for hearing aids as well? However, if there is a known threshold description for distortion that is not acceptable for a hearing aid, or to the hearing impaired listener, it appears to be in hiding.

Self-Generated Noise Levels

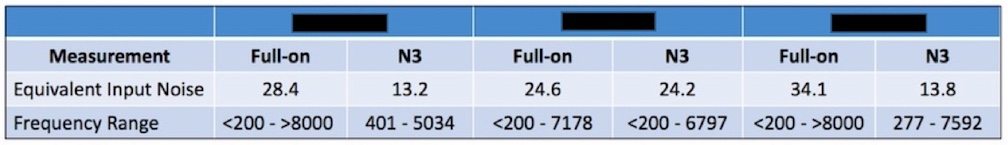

This measurement requires that the PSAP have programmable capability. If the PSAP has expansion, or other means to reduce low-frequency noise, and is not programmable, this measurement can be made, but comparison to other programmable devices (which many PSAPs are not) is not a fair comparison. The assumption should be made that all these measurements can be tested, as outlined, and as provided by the manufacturer. However, as seen in Figure 4, 32 dB is difficult to achieve even for premium-priced hearing aids. The full-on equivalent input noise of the right-side instrument exceeds this level.

Figure 4. Equivalent Input Noise levels for three premium-priced hearing aids as measured full-on. The instrument on the right would exceed the PSAP required levels. N3 is the audiogram to which each of the hearing aids was programmed (ANSI Standard Testing Hearing Aids – Part 2).

Category 2

Values that MUST be included.

This category does not include a threshold of acceptable range for the parameter measured. If this category does not include these, why is it that values MUST be included?

High Frequency Gain Provided

This is a current hearing aid measurement. It is difficult to imagine what this tells the consumer.

Battery Life

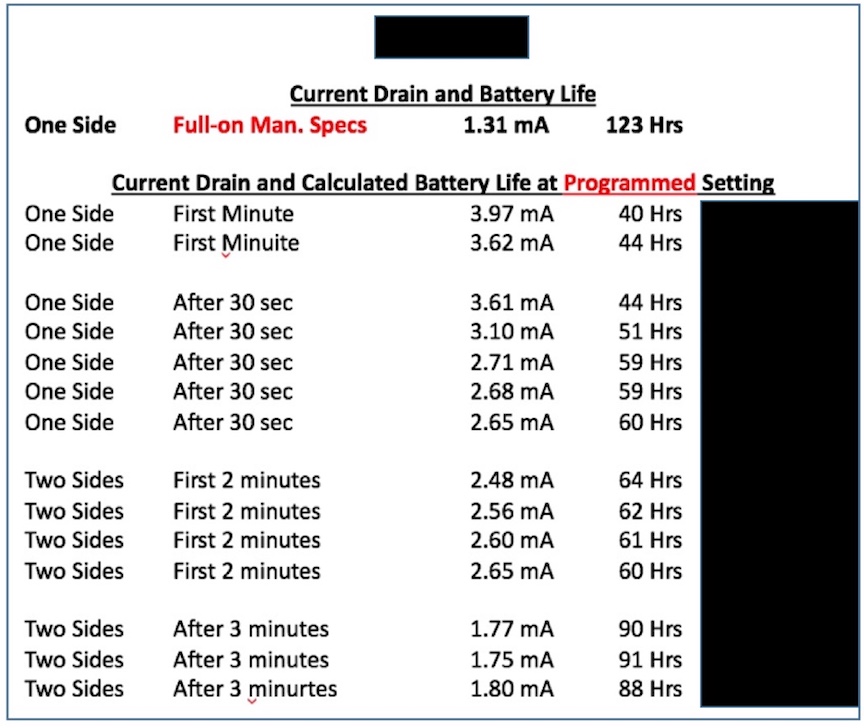

The proposed “Standard” states that the establishment of a common metric for battery life allows consumers to more accurately evaluate and compare devices. This appears to be the first measurement of use to consumers written in this “Standard.” This follows the current suggested procedure for measurement of hearing aids. Manufacturers are to report the estimated life for a single operating charge cycle with all optional features turned on and then/also(?) report the estimated battery life for a single operating charge cycle with all optional features turned off. Current hearing aids don’t have this requirement. It is unusual for hearing aid manufacturers to specify a particular battery manufacturer for their products (and it is known that each battery manufacturer has different mAmp capacity for the same cell as from another manufacturer), but this “Standard” requires this of PSAPs? This may not be realistic in that this demand is not even required for hearing aids. One would expect a premium-priced product to provide this information, but for a PSAP? Additionally, battery life can change rather dramatically for different environmental listening settings and as the use time lengthens, as shown in Figure 5 for a premium-priced hearing aid. This suggests again that PSAPs are to be held to a much higher standard than are current hearing aids.

Figure 5. Measuring and recording battery life is not as simple as using the formula provided. The formula does not take into consideration higher current drain measurements for certain settings, or the fact that the same size cell from different manufacturers has different mAmp capacities. How will the consumer know the mAmp capacity of a cell they purchase? This is not published on the battery packaging.

Latency

Again, a “not to be exceeded” time of 15 msec is not a standard with regular hearing aids. Again, a PSAP would be held to a higher standard.

RF-Immunity

Again, this seems to be a higher standard than with hearing aids.

Category 3

The technological capability or feature shall be reported in the device description. The specific value/metric for measurement for this value is not within the scope of the “standard”.

What is considered a technological capability or feature? Is amplification a technological capability or feature?

Fixed or Level Dependent Frequency Equalization – Tone Control

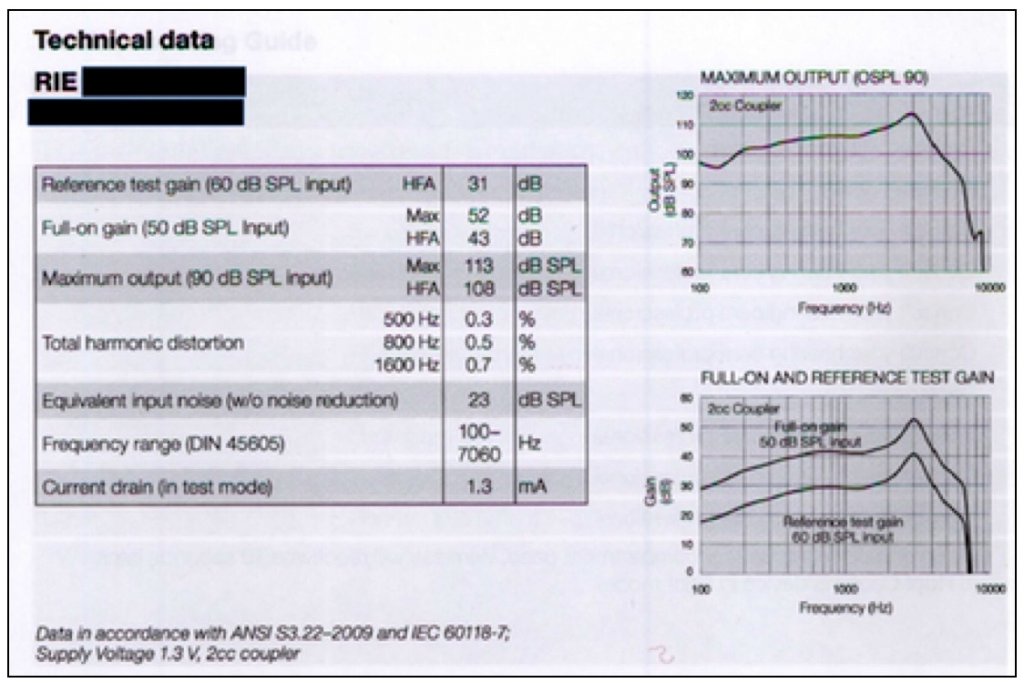

In a current User Instructional Booklet for a manufacturer of premium-priced hearing aids (Figure 6), this information is not required, nor is it provided. Again, the PSAP is being held to a much higher standard as none of this is required, nor present in materials to hearing aid customers.

Figure 6. This provides the technical data on a premium-priced hearing aid that is provided in a User Instructional Booklet. This is the “comparison” information that hearing aid users generally receive when they purchase a hearing aid. And, by the way, if they have already purchased in order to get this User Instructional Booklet, there is no longer a pre-comparison opportunity.

SNR Enhancement

The information asked for here seems to be missing in the requirements for hearing aids.

Noise Reduction

This is not seen in the User Instructional Booklet to the consumer. Therefore, how does a consumer make any judgments in traditional hearing aid comparisons? The fact is, that they don’t. Someone else makes that decision (rightly or wrongly) for the consumer.

Feedback Control / Cancellation

Evidence of such feature is not present in the User Instructional Booklet of Figure 6 for premium priced hearing aids, but expected for a PSAP. Having and stating that such a feature is available may be misleading to the consumer, because none of the feedback/cancellation systems, even in premium-priced hearing aids do not always eliminate acoustic feedback.

Specification and Reporting

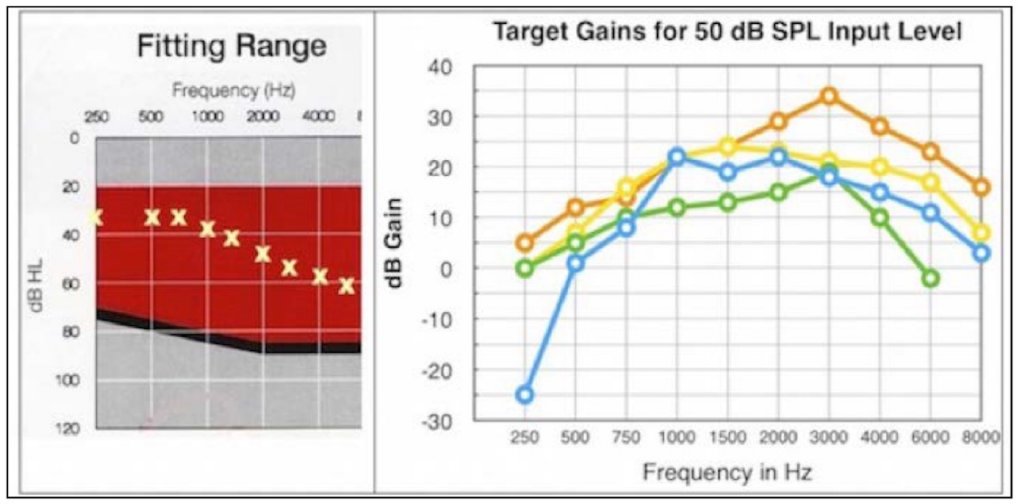

Compliance requires reporting a description of any personalized device functionality for a PSAP, but this is not required of hearing aids. What good is this anyway, when even with premium-priced hearing aids, the specification, especially the audiogram, provides little or no useful hearing aid fitting information (Figure 7) where the fitting targets are dramatically different by 4 manufacturers for the same audiogram. Shouldn’t this be required also of hearing aids?

Figure 7. Using the same audiogram (left), four premium-priced hearing aids provide very different target gains (right). Somehow, providing audiogram information to fit a PSAP is expected to assist the consumer (if it is available) when it can’t predict an optimum fitting for premium-priced hearing aids.

Device Coupling to the Ear

Measurements of open or adjustable fit coupling is not in this “Standard” (other than closed fit using a 2cc coupler). Therefore, what good is the frequency response curve at full-on gain when the majority of PSAPs are fitted using an open mold? How would this be measured in a 2cc coupler, and if measured that way, what would this tell anyone, including any hearing professional?

Wireless Connectivity

Again, not required of hearing aids, but mandatory for PSAPs.

Assumed to Apply to All Categories Since These Were Not Identified with Any One Category

Output Distortion

This requirement exceeds hearing aid standards. Hearing aid standards have no maximum distortion limitation. Distortion is whatever is measured. Why 5% for THD+N? Where is the research for hearing aids to support this level? This percentage appears to be completely arbitrary. Digital circuitry in hearing aids generally have THD percentages of less than 1%.

Because of this, some hearing aid engineers have suggested that they see little use in the THD in the current hearing aid standards, especially since most hearing aids are digital. So, why put it into PSAP “Standards” where development direction has been toward digital, the same as for hearing aids?

Input Distortion

Again, this is not a requirement of current hearing aid standards. No part of the current hearing aid standard asks for this measurement. And, what is magic about 5% THD+N?

Reporting

Wouldn’t it also be proper then that consumers were required to be given this information when purchasing hearing aids?

General “Category” Comments

The “Standard” is meant for PSAPs, but all the measurement procedures are those for hearing aids. Therefore, this is a hearing aid standard, or as designed, a standard that makes a PSAP a hearing aid.

Informal Listening Tests

Such tests are not required for hearing aids. The “Standard” states that this is “recommended,” but experience shows that “recommended” soon becomes “required.”

It is not clear which category is the highest. Is it Category 1 or Category 3? What is the difference between Category 1, 2, and 3?

This proposal is more complicated and detailed than are the current hearing aid standards.

How does any of this help the consumer make an informed comparison (especially when they have little or no idea what any of the measurements mean, or how does this help penetrate the untapped market?

Does the following identify this “Standard” correctly? Let’s make PSAPs meet most hearing aid requirements by requiring testing that may have no direct relationship to consumer satisfaction (remember, satisfaction includes not only listening, but cost, access, time, etc.). All the suggested measurements do not necessarily make the product better along these lines, but one can argue successfully that they will all increase the end cost to the consumer. If the measurement requirements are extensive enough, the product will have to be tested just like a hearing aid, adding costs, and moving the PSAP cost and description more in line with hearing aids. Which group benefits from this, the consumer or the traditional hearing aid manufacturer and dispenser? This “Standard” appears to be a “protection” publication for manufacturers and the current medical model of distribution, and not for the consumer.

If this “Standard” is voluntary, does this mean that PSAP manufacturers can sell their products without meeting any of these requirements? If they have to meet any of these requirements, then the “Standard” is not voluntary, but mandated.

It appears that this “Standard”, as written, is an unnecessary intrusion into assisting individuals with mild-to-moderate (and perhaps even to severe) hearing levels, from purchasing products that they find useful to them, that they could purchase OTC.

Acceptance to Hearing Aid Manufacturers and Dispensers

They will like this “Standard”. It helps maintain the status quo and adds a multitude of restrictions to PSAPs not even suggested for hearing aids. This “Standard” makes basic amplification devices regulated just like hearing aids, except even more stringently. It is difficult to see any real differences between this and the current hearing aid Standards that would put PSAPs at a lower measurement involvement level.

References

- ANSI/CTA Standard – Personal Sound Amplification Performance Criteria, ANSI/CTA-2051

OTC Hearing Aid Standard

Originally posted July 25, 2017. Reprinted with permission.

Both PCAST1 (President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology) and NAS2 (National Academies of Sciences) have recommended that OTC (over-the-counter) hearing aid sales be permitted for mild-to-moderate hearing losses. Additionally, the SB 9 Over-the-Counter Hearing Aid Act of 2016 introduced by Senators Warren and Grassley calls for the same. These recommendations resulted from the identification of problems with the current hearing aid distribution system that prevents an increasing number of individuals from hearing amplification help (both in accessibility and affordability). As part of recommendations, there has been talk about on OTC hearing aid standard.

Among the early advocates during IOM (Institute of Medicine) meetings for hearing aids as a consumer product, and not a medical product, was the Consumer Electronics Association (CEA; now renamed the CTA – Consumer Technology Association). Strong opposition came from the Hearing Industries Association (HIA).3

During June, 2017 meetings conducted by NASEM (National Academy of Science, Engineering and Medicine) in continuing meetings to the IOM, content was devoted to accessible and affordable hearing care for adults as the overall agenda. An additional topic of some discussion related to an attempt to write “standards” for OTC (over-the-counter) hearing aids. This was offered by CTA as to what some referred to as a reasonable starting point for an OTC hearing aid.

The irony is that the June 9th meeting suggested, among their recommendations, the following:4

- Empower consumers and patients in their use of hearing health care

- Improve access to hearing health care for underserved and vulnerable populations

- Implement a new FDA device category for over-the-counter wearable hearing devices

- Improve affordability of hearing health care by actions across federal, state, and private sectors

- President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. (2015). Aging America & hearing loss: imperative of improved hearing technologies. http://www.hearingreview.com/wp-content/uploads/hearingr/2015/10/PCAST-Slides.pdf?5036bc.

- National Academies of Sciences Engineering Medicine. (2016). Hearing health care for adults: priorities for improving access and affordability. http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2016/Hearing-Health-Care-for-Adults.aspx?utm_source=HMD+Email+List&utm_campaign=f6d2ada521-Hearing+Health+Care+for+Adults&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_211686812e-f6d2ada521-180442165.

- Hearing Industries Association. (2016). Paper presented to the Institute of Medicine (IOM) in support of its efforts on accessible and affordable hearing health care for adults as well as to the PCAST Report. http://www.hearing.org/uploadedFiles/Content/HIA_Updates_and_Bulletins/HIA White Paper on Hearing Health – 2015.pdf.

- The National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Health and Medicine Division. (June 2, 2016). http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report Files/2016/Hearing/Hearing-Recs.pdf.

- Regulatory Requirements for Hearing Aid Devices and Personal Sound Amplification Products – Draft Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. Docket FDA-2013-D-1295. (2009).

- FDA U.S. Food & Drug Administration (2013). Regulatory requirements for hearing aid devices and personal sound amplification products – draft guidance for industry and food and drug administration staff. (new guidance document suggested). https://standards.cta.tech/kwspub/published_docs/ANSI-CTA-2051-2017_Preview.pdf.

- Bose Corporation Comments. To: Division of Dockets Management (HFA-305), Food and Drug Administration, re: Draft Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administrative Staff: Reopening of the Comment Period. Submitted electronically, May 5, 2016.

- Telecommunications Industry Association. (2014). Comments of the Telecommunications Industry Association to the Food and Drug Administration’s Regulatory Requirements for Hearing Aid Devices and Personal Sound Amplification Products – Draft Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff (Docket No. FDA-2013-D-1295). Comments of the Telecommunications Industry Association to the Food and Drug Administration’s Regulatory Requirements for Hearing Aid Devices and Personal Sound Amplification Products – Draft Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration.

- For example, a recent survey by Consumer Reports found that hearing aids ranged from $1,800 to $6,800 per pair in the New York City metropolitan area. See http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/hearing- aids/buying-guide.htm. See also The Hunt for an Affordable Hearing Aid, http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/10/22/the-hunt-for-an-affordable-hearing-aid/.

- See Food and Drug Administration, mobile medical applications: guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration staff (2013) at 8 (“MMA Guidance”), available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/UCM 263366.pdf.

In trying to meet these recommendations, the FDA’s Draft Guidance (2013) goal was to provide clarity in what it defines as a hearing aid as opposed to a PSAP. This clarity, in the FDA’s thinking was intended to encourage greater innovation in the area of sound amplification devices as well as the avoidance of improper application of regulatory requirements to regulated and unregulated products. This Guidance would have a direct effect on the ability of millions of Americans to make informed purchases of products to improve their hearing. If this was the stated effect, the Guidance should be written and applied in such a way that it avoids roadblocks that distract from the stated goal – easy and low-cost access to hearing amplification products.

Recall, the NASEM meeting priorities were to improve access and affordability. Nowhere did it recommend that the process be made more difficult, and costly, which is essentially what the CTA (ANSI/CTA-2051) recommended “standard” for PSAPs, and by extension, for OTC hearing aids seems to be directed towards.

In about 1975, the hearing aid industry was considered to have reached a market penetration of about 27%. Today, it is more closely to 17%, even though more hearing aids are sold. This is due to the ageing of our citizens, and there is no practical way that there will be the number of audiologists/dispensers to manage the hoped-for increases in market penetration. There are many reasons for not increasing market penetration, among which cost is always considered a barrier – perhaps not number 1 on the list, but always there somewhere in the top tier of reasons why hearing aids have not been purchased. Additional issues relate to ease of availability, and meeting basic needs.

What Happened to the CTA?

The CTA (Consumer Technology Association), which originally positioned itself in favor of less restrictive regulations for amplification devices5, then surprised many with their publication of “scientifically defensible voluntary manufacturing standards and performance criteria” for PSAPs6. To complicate the issue further, the Hearing Industries Association (HIA), a trade organization of hearing aid manufacturers, asserted its belief that if an OTC category is to be created, that it should meet the same FDA standards as existing hearing aids and should be offered only to people with mild hearing loss. Note that moderate and greater hearing losses would be left out, but with no explanation as to why, making it more restrictive than what had been proposed (mild and moderate hearing losses). Also, if the OTC category was to meet the same FDA standards as existing hearing aids, then why should they be limited to only mild hearing losses? After all, they would have met all the requirements for traditional hearing aids.

Is There a Need to Differentiate Between a PSAP and Hearing Aid?

Many people consider a hearing aid and a PSAP to be the same product – both of which should be available as OTC sales with as little or as much support as the consumer demands. Attempts to differentiate these products based on the level of a person’s hearing loss and/or basic performance is completely arbitrary, without evidence, and totally uncontrollable. Powerful and convincing arguments were made against limitations to OTC use during the comment period (FDA Docket FDA-2013-D-1295-0048) by Bose Corporation, citing past and current research.8

Is There a Role for PSAPs, as Defined by the FDA?

With an OTC market, the answer is “no.” As an OTC hearing amplification product, the PSAP and hearing aid perform the same function and serve much of the same population. If this is the case, there is no need for the CTA ANSI/CTA-2051 PSAP standard proposal. But, because this proposed “standard” has received attention, it is important to review it, so that all have a real understanding of what it calls for. That is what the next few posts will do – somewhat on a line-by-line discussion.

In a move that would make sense (but something not to be expected), the FDA could resolve much of this uncertainty by adopting a de-regulatory approach as suggested by the TIA (Telecommunications Industry Association) to the FDA relative to the PSAP Guidance of 2013:9

“FDA could resolve much of this uncertainty by adopting a de-regulatory approach and using its enforcement discretion. Such an approach would be consistent with the FDA’s mobile medical applications guidance, which made clear that certain mobile applications subject to FDA enforcement which posed little or no risk to consumers would qualify for this discretion, because the resources spent on regulating them outweighs the degree of their risk to consumers.”10

The FDA, through that referenced guidance, proactively chose to express its intention to exercise “enforcement discretion” on several types of mobile medical apps posing low risk to patients. This, even though they might meet the statutory definition of a medical device. FDA stated that it does not intend to enforce requirements under the Food Drug and Cosmetic Act.11 In a similar way, although some PSAP/OTC hearing aids and apps might quality as medical devices because of their inherent functionality, the FDA could easily exercise enforcement discretion because they pose such a low risk of harm to consumers and their availability to the general population far outweighs burdensome requirements which make little sense to enforce. Additionally, discussion continues as to whether hearing aids/OTCs are medical devices or consumer products.

ANSI/CTA-2051 (Proposed “Standard”) for PSAPs

What is this suggested “Standard?” Regulations to meet a “Standard” necessarily involves additional costs to produce and market a product. It is not clear as to how this is going to help the consumer when these “Standards” appear to intentionally and primarily lead to increased costs.

If the intent of all of these IOM, FDA, NAS, and NASEM meetings and discussion was to get more amplification products to the untapped consumer market, this “Standard” definitely works against that.

If the concern is about consumer safety, this “Standard” posts only a single “safety” measure – that of limiting the output of the device. This suggests that the safety issue may not be real, but imagined. Should a product be forced to protect everyone? Not so. For example, even OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration) permissible noise levels are designed to protect only about 90% of the population.

In reading the proposed “Standard,” it appears that how one accepts this recommended “Standard” depends clearly on how the OTC hearing aid is considered to be marketed/distributed, and by whom.

Is Such a “Standard” Even Necessary or Justified?

To understand this question, it is important to review some of the background and questionable assumptions leading up to this suggested “Standard.” To shed some light on this question, a series of posts that follows, provides a review and commentary on the proposed ANSI/CTA-2051.

References

PSAP Standard Review

Originally posted on August 1, 2017. Reprinted with Permission

Legislation recently passed in the U.S. House of Representatives1 and expected to be passed soon in the U.S. Senate2, requires the FDA to establish an OTC (over-the-counter) hearing aid category for adults with perceived mild-to-moderate hearing impairment, within three years. This category is estimated to overlap the hearing levels of approximately 60-80% of all hearing aids sold in the U.S. market today. Related to the legislation, a proposal has been made for a measurement procedure, identified as a PSAP Standard, but that is where the confusion starts.

These bills would leave it up to the FDA to determine what form the regulation will take. This uncertainty will have the different factions (few restrictions vs. maximum restrictions) jockeying for position.

The major change relating to OTC hearing aid sales is likely to be that a licensed person would not be required to make a sale. What other types of “regulations” related to products to be sold still awaits to be seen, but it appears that at least one attempt that primarily looks at measurement of OTC hearing aids has been proposed – in the form of a PSAP Standard. How minimal or extensive the oversight will be by the FDA is not known at this time. It is suspected that this will all depend on how serious the FDA will be to provide the charge given to them for accessibility and affordability of hearing amplification help.

Enter the CTA (Consumer Technology Association)

January 2017, the CTA proposed a “standard” to determine PSAP performance. The document was titled “ANSI/CTA Standard – Personal Sound Amplification Performance Criteria, ANSI/CTA-2051.3 This was stated, as designed, to serve the public interest through eliminating misunderstandings between manufacturers and purchasers, facilitating interchangeability and improvement of products, and assisting the purchaser in selecting and obtaining with minimum delay the proper product for the hearing-impaired consumer’s particular need. Any “Standard” with such lofty and variable goals is subject to serious analysis.

The remainder of this post, and the series that follows, will comment on different sections of the CTA-1051 proposal.

Relative to stated purposes, the “Standard” seems to initially have missed its mark.

- The “Standard” is written for PSAPs. Will there actually be a PSAP category with new OTC legislation?

- Regulations to meet a “Standard” necessarily involve additional costs to produce and market the product. How is this going to help the consumer when these “Standards” realistically lead to increased costs, which will be passed on to the consumer?

- If the intent of all of the IOM (Institute of Medicine), PCAST (President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, NAS (National Academies of Science, NASEM (National Academy of Science, Engineering and Medicine, MDIFA (FDA Medical Device User Fee Amendments Act of 2017), meetings and discussion was to get more amplification products to an untapped consumer market requiring accessibility and affordability, this “Standard” works against those goals.

- The proposed “Standard” states a concern for consumer safety. However, safety features are AWOL in this “Standard,” other than the single one found that limits the output level.

Change Name of “Standard” from PSAP to GSAP (general sound amplification products)

It seems that the name of this proposed “Standard” should change from PSAP (personal sound amplification products) to GSAP (general sound amplification products). As a consumer product, OTC amplification products should be viewed the same way as are earbuds, smart phones, iPods, etc. These products are designed for general use, not personal (suggests prescription) use. While these products are not intended to be personalized, as are hearing aids, people that use these products have the same general hearing levels as the general population. Are smart phones, earbuds, iPods, radios, etc. therefore personalized as are hearing aids? In reality, these products are used also to provide personal sound amplification and/or enhancement to a user. So, in this sense, they are personalized, even though the personalization is performed by the consumer. How well would a “Standard” be accepted that would impose the same measurement requirements on these products as are being proposed for PSAPs?

If for PSAPs, Then Why Referencing Hearing Aid Standards?

The ANSI/CTA “Standard” reads just like an ANSI hearing aid test Standard. This “Standard” puts PSAPs and hearing aids in the same category, except that requirements for PSAPs are much higher than for hearing aids. That being the case, should all such products in this “Standard” be identified as PSAPs or hearing aids?

Is This a Hearing Aid Standard or a PSAP “Standard?”

The way this is written, it would seem reasonable to replace the current ANSI HA Standards with this proposed “Standard.” This statement means that although this is presented as a PSAP standard, it is essentially a hearing aid standard, using the same measurement features and references, but actually even more stringent than current hearing aid measurement standards in many ways. Why not just call it what it is: A hearing aid standard that is somewhat different than the current ANSI HA Standard, but in most ways, for a PSAP, more stringent than the current hearing aid measurements.

Scope

As written, this document applies to hearing aids as well: “...products that provide personal sound amplification and/or enhancement to a user.” That is exactly what hearing aids do. There is no differentiation in the Scope, so this proposed “Standard” should apply to hearing aids as well.

Safety

The “Standard” states that it does not purport to address all safety problems associated with the product’s use. It was right on the mark with this one. In fact, the only safety measure addressed is that of the SSPL90 maximum. This could be done with a simple statement, not requiring a “Standard.” This is also the only, and same, safety measure addressed for hearing aids.

Definitions

The purpose of these for PSAPs is definitely not clear. How will definitions of electroacoustical performance assist the general consumer – definitions that most hearing professionals may not fully understand? Perhaps a few additional definitions should be thrown in to make this seem more impressive, and more confusing. It is difficult to see how this section helps consumers or expands the market. Why is there a concern about such definitions? Are these to be posted in materials for the consumer? These appear to be more important for hearing aid designers than for PSAP designers. This is more complicated than it needs to be.

Symbols and Abbreviations

It is not clear who these symbols and abbreviations are for. If for the designer, they should already be known and understood. If for the consumer, how do they use/compare terms like CORFIG, RECD, SNR, SPL, dBA, etc.? How do these help the consumer compare PSAPs? If not, why are they included? The information that follows relates to specific sections of the proposed ANSI/CTA-2051 “Standard.”

And, these comments are only the start. More will be made in following posts, with the next post looking at the “Categorization” of hearing products.

References

- S. House of Representatives. H.R. 2430 – FDA Reauthorization Act of 2017. July 13, 2017.

- S. Senate. S9 – Over-the-Counter Hearing Aid Act of 2017. https://www.warren.senate.gov/files/documents/3_21_17_Hearing_Aids_Bill_Text.pdf.

- Consumer Technology Association (CTA). (2017). ANSI/CTA Standard. Personal Sound Amplification Performance Criteria. ANSI/CTA-2051. https://standards.cta.tech/kwspub/published_docs/ANSI-CTA-2051-2017_Preview.pdf.

OTCs: The End Is Near

Originally posted July 25, 2017. Reprinted with permission.

“Peeling the Onion” is a monthly column by Harvey Abrams, PhD.

It appears that the creation of an FDA-sanctioned category of over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aids is a fait-accompli (which is a French-Audiology expression meaning “The End is Near”).

For those of us who plan to survive this end-time, I wonder if it might be a useful exercise to imagine what a world with OTC devices might look like and how the professional community might respond.

So, I’m suggesting we perform a small thought experiment. And here are the assumptions:

- OTC hearing aids are approved for adults with mild to moderate hearing loss

- A hearing test is required as a condition of purchase (I know, this is probably a stretch from an enforcement perspective but this is my thought experiment)

Three Models

What, then, might be some ways that the consumer can purchase an OTC hearing aid? There appear to be 3 possible models. The American Academy of Audiology (AAA) published a brief description of a few direct-to-consumer (DTC) delivery models.

- Predominately online

- Predominately brick & mortar

- Some combination of the two

Predominately Online

The online model will involve some level of remote selection and programming based on a recent audiogram. This option is really not a “thought experiment” as it already exists.

An example of this model is provided to UnitedHealthcare insurance subscribers through its HealthInnovations (hi) subsidiary. Subscribers can call a toll-free number to get a hearing test scheduled through one of their participating specialists or, if the member already has had a hearing test completed within the last year, they can send it (fax, mail, scan) to hi after which someone will contact the subscriber with a device recommendation. If the consumer agrees to purchase a device, a pre-programmed hearing aid will be mailed to them. In terms of support, the company provides text-based information, instructional videos and daily group Q&A sessions through their website or the consumer can call, FaceTime, or video chat with an “expert.”

Other examples of this model include America Hears and HearSource, both of which will mail a pre-programmed hearing aid to the consumer based on a recent audiogram. Post-sales support, including assistance with their self-programming kits, are available through phone communications. The ability of OTC users to successfully self-fit their hearing aids is an issue that was recently explored by Wayne Staab in a recent HHTM post.

Predominately Brick & Mortar

I’m envisioning a kiosk at a big box store (next to the blood pressure machine) which will test the consumer’s hearing and recommend a particular device from among a color-coded selection of OTCs on a rotating display (you know, similar to how readers are displayed). For example, the screen on the kiosk will read:

“Based on your test results, we recommend the WhisperTone 450 model in the yellow package.”

If the consumer buys the device, post-sales support would be available online or via a toll-free number. A variation on this theme might include a questionnaire as part of the hearing test. The answers would determine the “appropriate” level of technology:

“Based on your answers to our questions and your hearing test results, we recommend the WhisperTone EX-450 model. Please choose your method of payment.”

Hybrid

This would involve either the testing or device delivery and programming being provided at a physical location or online. A few possibilities:

- The consumer completes an online test at WhisperTone.com and brings the results to an approved provider who sells WhisperTone devices.

- The consumer receives an evaluation at a clinic and purchases their device and self-fitting kit online.1

Audiologists in the Models

How does the audiologist fit into any of these models? Each practitioner will need to determine the extent to which they want to be involved in DTC sales. But the delivery models described above provide some real opportunities for the audiologist.

For example, following the hearing evaluation the audiologist can guide their patient toward an appropriate OTC purchase (which might include a selection for sale in the practice). This approach means NO MORE FREE HEARING TESTS. Another opportunity is to provide post-purchase services to consumers who need counseling, education, adjustments, repairs, etc. for devices they’ve purchased on line. This approach means NO MORE BUNDLING. AAA published a brief guide on how to manage patients who have purchased their hearing aids through a DTC vendor.

The End Isn’t as Near as It Looks

There’s still plenty of time and many steps ahead before OTC hearing aids become the law of the land:

- The Senate needs to pass their version of the legislation

- The two houses need to reconcile any differences

- The President needs to sign the bill into law

- The FDA has to create and publish a draft OTC regulation consistent with legislative intent

- The draft regulation needs to be made available for public comment

- The FDA needs to consider those comments after which the final version will be published and entered into the Congressional Record.

So, in the time we have remaining prior to the final promulgation of the FDA regulation, let’s engage in some more thought experimentation to envision how we can take full advantage of a new opportunity for our profession.

Footnotes

1By the way, I just checked and the WhisperTone.com domain name is still available for purchase!