Sign Languages of Canada: The Canadian Language Museum’s Newest Travelling Exhibit

The Canadian Language Museum (CLM) is a small museum with an extensive reach. Located in Glendon Gallery on the Glendon College Campus of York University in Toronto, its exhibits have been displayed from coast to coast to coast: from Victoria to St. John’s to James Bay. It is the only museum in Canada devoted to linguistic heritage and one of the few language museums in the world.

The CLM celebrated its 10th anniversary in 2021, and central to the celebrations will be the opening and touring of its newest exhibit, Sign Languages of Canada. This is the eighth travelling exhibit created by the CLM about Canada’s languages.

The CLM’s unique travelling exhibit program first began out of necessity: at the time of its founding, the CLM had no exhibit space, so we decided to reach the public through travelling exhibits. Our limited budget led us to a highly successful model: we use light double-sided banner-stands to display the English and French text. Each exhibit comprises six or seven stands which pack compactly into two-wheeled bins, and can be shipped easily by car, bus, train, plane, and boat. Not only are the banner stands relatively inexpensive to ship, but their set-up can be easily individualized to the hosting venue, such as a school, library, community centre, small museum, or public building.

Like the previous exhibits, the Sign Languages of Canada exhibit consists of 7 double-sided banner stands, with one side in English and French. A challenge with our earlier exhibits, which we met in many ways, was to add audio elements that could easily travel. With this exhibit the challenge was to add visual material that would be completely accessible to a deaf audience. As a result, we have incorporated videos about the different sign languages through QR codes on the text panels and programmed them onto accompanying tablets.

The CLM’s mandate is to promote an appreciation of all the languages used in Canada. Over the past 10 years, we have created exhibits about our two official languages, English and French, and the two largest Indigenous languages: Cree and the Inuit language. In addition, there is an exhibit that introduces the viewers to all of the languages spoken in Canada, one that traces the changing linguistic landscape of Toronto, and an exhibit that explores the changing relationship between dictionaries and Indigenous languages. The CLM was founded during the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and has felt a particular responsibility to represent and promote the Indigenous languages used in Canada.

Our exhibits to date have focused on oral languages, and we felt strongly that it was important to have an exhibit about sign languages as well. We want to spread awareness that sign languages are complete languages in themselves, distinct from the spoken and written languages used around them. Canadians should know that many different sign languages are used in Canada, each with its own vocabulary, grammar, and culture.

From its first year, the CLM has benefitted from working closely with university students to create its exhibits. For example, students from the Master of Museum Studies Program at the University of Toronto have been involved in curating each of the museum’s exhibits, and four students from that program worked on this exhibit. In addition, students at Glendon College created a video to accompany the exhibit and translated the text into French.

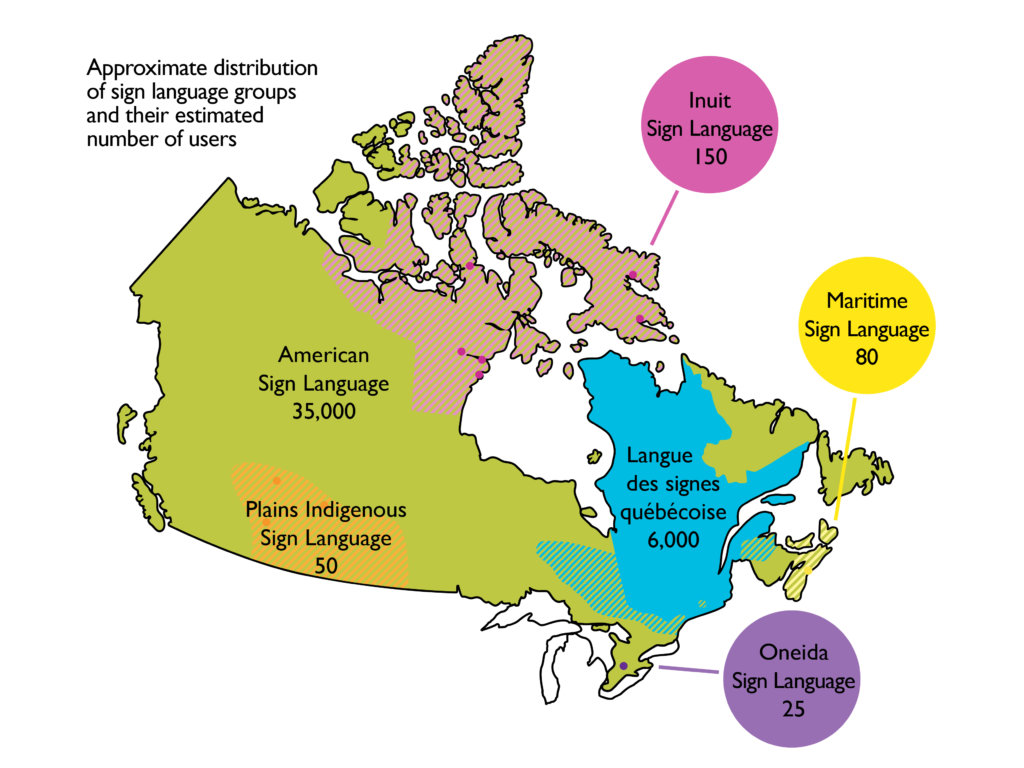

When we started this exhibit, we were aware of three sign languages in Canada: American Sign Language (ASL), Langue des signes québécoise (LSQ), and Inuit Sign Language (ISL). In our research we learned about three more: Maritime Sign Language, Oneida Sign Language, and Plains Indian Sign Language. To develop the exhibit content, we consulted with several teachers, researchers, and members of the different sign language communities, both deaf and hearing.

ASL is the best known of these languages and is used across Canada, primarily in English areas. LSQ is used where French is spoken, mainly in Quebec, northern Ontario, and New Brunswick. As the name implies, Maritime Sign language is used in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island. The Inuit Sign Language is used in Nunavut, particularly along the west coast of Hudson Bay and on Baffin Island. The Oneida Sign Language is being developed in southwestern Ontario, near London. Finally, Prairie Indian Sign Language is used in Canadian prairies, primarily in Saskatchewan and Alberta.

Many people don’t realize that ASL and LSQ are sister languages – they both grew out of a sign language from France that was developed in the late 1700s. ASL began at a school for the deaf in Connecticut, founded in 1817 by Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, a hearing American, and Laurent Clerc, a deaf Frenchman. ASL developed from a combination of the French sign language with signs already used by deaf Americans. Despite its French origins, ASL is now primarily associated with English.

LSQ developed in Quebec in the 1800s from the French sign language brought over by teachers from France. Many signs, like those for where and how are the same in LSQ as in contemporary French Sign Language; other signs are similar to those in ASL or are unique to LSQ. We were intrigued to discover that LSQ has developed some synonyms because deaf boys and girls had been taught separately in Quebec Catholic schools. The nuns modified some signs to make them more modest for the girls, and today both variants are in use.

Maritime Sign Language is the only sign language used in Canada based on British Sign Language. British Sign Language users brought the language to the Maritimes when they emigrated from Great Britain. Some Canadian deaf children were educated in Britain and brought the language back with them. MSL was taught at schools for the Deaf in Nova Scotia in the 1800s and early 1900s. However, today MSL is considered to be an endangered language – it is mainly used by elderly people, with few young people learning it.

The Oneida Sign Language is a newer creation: it is being developed by members of the Oneida Nation of the Thames in southern Ontario. Marsha Ireland, a leader in its development, is very passionate about the need for deaf Indigenous people to relate to their heritage through sign language based on their own language. More than 250 signs have been developed so far.

The Inuit Sign language (ISL) has a long history of use across Nunavut. Knowledge of ISL was widespread among hearing Inuit, providing a wide support network for deaf Inuit. However, with the use of ASL spreading in Nunavut, fewer young people have been learning ISL. The Canadian Deafness Research and Training Institute in Montreal has worked with the Nunavut Deaf Society to record and revitalize ISL.

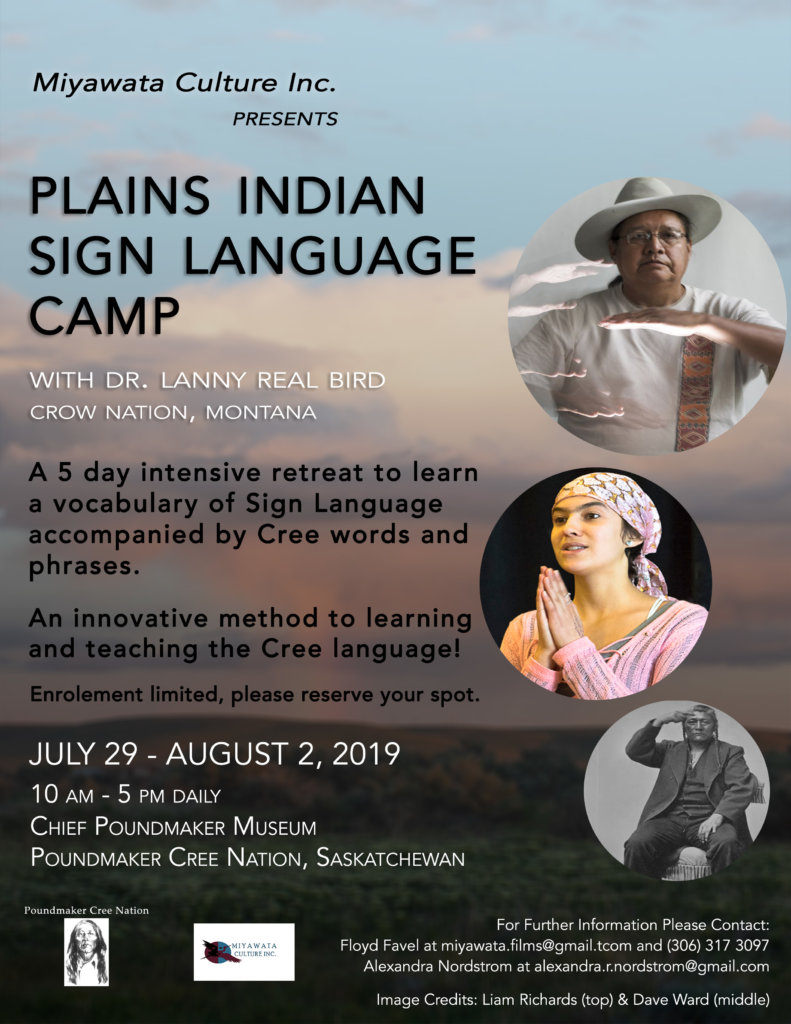

PISL, the Plains Indian Sign Language, is probably the oldest of all the sign languages described here. It was used extensively across the North American prairies before contact with Europeans. Unlike the other sign languages, it was used by hearing individuals in a wide variety of situations. Signs were used to enhance storytelling and religious ceremonies, to communicate across wide distances or when silence was necessary. PISL was also used as a lingua franca, for communication between Indigenous nations that spoke different languages. It was already evident in 1930 that young people were no longer learning PISL, when the Smithsonian Institute brought together leaders from other Indigenous nations to record their sign language. Today the Chief Poundmaker Museum in Saskatchewan is working to maintain and revitalize PISL.

Any discussion about languages in Canada must include sign languages and recognize the existence of Indigenous sign languages and those used in anglophone and francophone Canada. Indigenous and non-Indigenous sign languages have achieved some legal recognition in two recent Acts of Parliament (2019). The Accessible Canada Act states: “American Sign Language, Quebec Sign Language and Indigenous sign languages are recognized as the primary languages for communication by deaf persons in Canada.” Bill C-91 An Act Respecting Indigenous Languages gives as its first purpose, to “support and promote the use of Indigenous languages, including Indigenous sign languages.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought new attention to sign languages, with signing interpreters sharing the stages with physicians and politicians as they address the public. Unfortunately, Covid-19 has also closed the Canadian Language Museum’s doors and delayed the launch of this exhibit. We look forward to easing pandemic restrictions when we will be able to fully celebrate our 10th anniversary by touring our exhibit Sign Languages of Canada to deaf and hearing audiences across the country.

For more information about this exhibit and links to videos about the different sign languages, visit the exhibit’s webpage at:

languagemuseum.ca/exhibit/sign-languages-of-canada

The French version can be found at:

museedeslangues.ca/exhibit/les-langues-des-signes-du-canada

Additional Resources

LSQ: https://youtu.be/tQ1c6SFawAE

Art Gunter– Deaf Experience: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zj3JAidi4tc

Learning ASL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cbNkHbzfClA