“It’s Not Denial. It’s Observation” Why People Find it Difficult to Detect Changes in their Own Hearing and Implications for Hearing Care Providers

Reprinted with permission from The Hearing Review

Introduction

Hearing healthcare professionals (HHP) are socialised into the belief that people with hearing loss are “in denial”. This belief is reinforced when individuals who later “accept their hearing loss”, and subsequently begin using hearing technology, look back at their earlier failure to recognise the now obvious reduction in hearing, and try to rationalise their failure by adopting the explanation of “denial” given by the HHP.

The assumption of denial is so well-established that it is seldom questioned, so when patients offer their own perspective — “My hearing’s not bad” or “I hear everything I want to hear” or “I find some situations a challenge” — it is automatically seen as evidence of their denial (see, for example, Kochkin, 2007).

This presupposition of denial leads to ‘rehabilitative’ strategies that aim to break down a person’s resistance, where the perspective of two parties (HHP/Significant Other—vs—Client/Patient) are pitted against each another in a winner-takes-all contest. The social sciences teach us that such an approach is likely to fail and even strengthen a person’s resistance (see Knowles & Linn, 2004). Ultimately “people persuade themselves” (Perloff, 2010) and the role of the HHP should therefore be to facilitate that.

The purpose of this article is to provide practical insight into this putative denial, demonstrate how we can reframe it to better align with a client/patient’s own perspective, and examine implications for the provision of hearing healthcare. The result will be to create the necessary conditions—capability, opportunity and motivation—for behavioural change (e.g. the increased uptake of hearing technology) to take place (Michie et al., 2011).

Part 1: Why it’s So Difficult to Perceive Changes in Hearing

Challenge One: You Can’t Perceive What Doesn't Exist

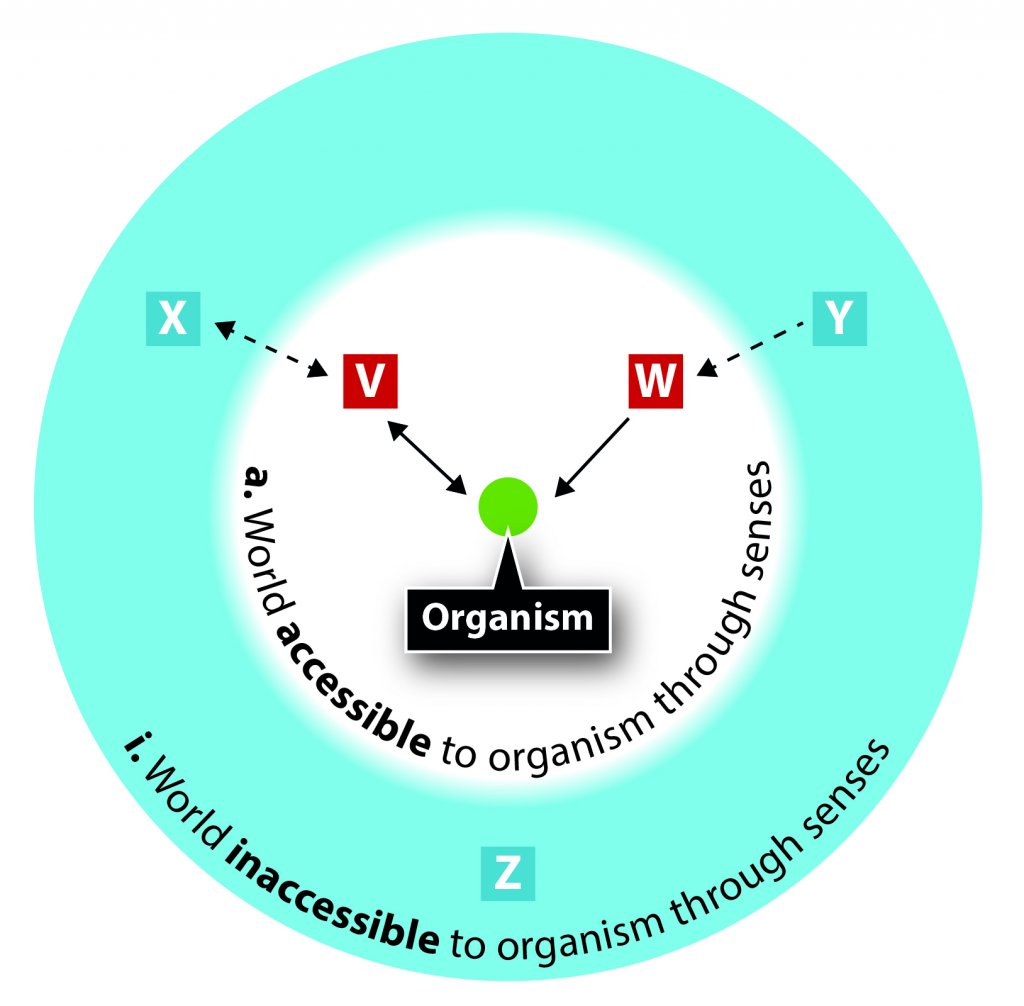

There is a concept in the study of animal and human behaviour called umwelt (von Uexküll, 2014). It describes how our own perception of the world is shaped and limited by our senses (see Figure 1), and ‘reality’ will therefore differ from one organism to another. A bee’s reality, with its ultraviolet vision, will be very different from that of a shark equipped with electroreception, which will differ again from our own experience of the world as humans.

Figure 1. Every organism (e.g. a bee, shark, human) experiences the world through its senses, which either make things accessible (a) or inaccessible (i). So [V] and [W] are things that are accessible to this organism. If the organism were a bee, then it may be the patterns on the flower that are accessible to it through its ultraviolet vision. The organism can interact with these things (bidirectional arrow shown between [V] and organism) or receive information from it (unidirectional arrow from [W]) The things [X], [Y] and [Z] are inaccessible to the organism through its senses. However, the organism may still be able to deduce its existence through its interaction with [X] and [Y]. Applied to hearing, sounds such as bats or a dog whistle are inaccessible to us, so are represented by [Z], whereas the sound of a washing machine or human speech is accessible [V] and [W]. However, if our hearing range contracts, other sounds may fall outside of our hearing range too and become inaccessible [X] and [Y]. We may be able to deduce their existence only through their interaction with other people for whom they are accessible or through information received through our other senses, or through previous experience (memory).

Applied to hearing, if a sound falls outside of our own hearing range, that sound ceases to exist for us; it is no longer part of our reality. The signal may be present in the environment, but we have no access to it, and therefore it has no meaning for us. Imagine if dogs could talk and the arguments we might have over the sound of a dog whistle. From the dog’s perspective, we’d be “in denial.” But for us, it’s simply observation.

We might extend this further. If our own hearing range has contracted to the point it is now excluding sounds audible to other humans, we have a clash of realities. It’s not that we can’t hear those sounds; they simply don’t exist.

The exception is if we have some visual (or other sensory) indication to highlight the ‘non-existent’ sound, such as a bird moving its beak with no sound emanating, or a violinist moving their bow across the strings in utter silence. But for such events to occur at the precise moment our attention is directed towards them relies primarily on serendipity.

The other exception is if someone with us happens to hear a sound and comment on it, and we trust that person enough to believe they are telling us the truth, and there is nothing salient in the environment that could be put down as a more ‘obvious’ reason for not hearing hear it (e.g. “My friend has exceptionally sharp hearing”), the so-called Illusory Causation Effect (Lassiter et al., 2002; McArthur, 1980, 1981). The probability of all three criteria being met is remote.

In each of these exceptions there is an underlying theme: the luxury of comparison. In the first case the presence of the sound is deduced only by a comparison with information available from another sense such as the visual system. In the second we are comparing our experience with that of another human, our social system. In both cases reliance is made on cognitive systems such as associative and autobiographical memory, as well as theory of mind.

So for another human being to tell us we are “in denial” is unfair and inaccurate. Because for us, it’s observation.

Challenge Two: Chasing a Moving Target

Sound, by its very nature, is a moving target. The same sound can be louder or quieter for all sorts of reasons. Experience tells us that some sounds on TV are quieter or louder than others, which is why we have a volume control. We also know that information contained in a signal can be weakened or distorted:

- People do sometimes ‘mumble’, for example someone who is shy (Zimbardo et al., 1977) or depressed, (Mundt et al., 2007).

- The TV can sound distorted (e.g. poor microphone placement during a recording; an old recording).

- The environment can be echoey and smear speech.

- Enough noise will interfere with the signal through energetic and informational masking (Brungart et al., 2001).

- People do appear to speak more quickly today than “yesterday” (For example, see: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/how-technology-is-turning-us-into-faster-talkers-1.1111667)

A lifetime of experience will inform us that any difficulties we may be experiencing with our hearing now is likely to be a further example of such situational factors (see Nickerson, 1998), and so to counteract the present compromise in signal we can employ the same compensatory measures that have worked for us in the past: moving away from the noise, closer to the signal, adjusting the volume, or conversational repair strategies (Lind et al., 2004).

We may need to use such measures more frequently, but who’s keeping count?

Challenge Three: Taking One for the Team

Hearing works in partnership with a number of other systems, including the visual system (McGurk, 1976; Stein & Stanford, 2008), the cognitive system (Zekveld et al, 2006; Mattys et al, 2012) and our social system (Hyashi et al., 2013).

These three systems each contribute information from which the overall gestalt emerges, each seamlessly compensating, where possible, for any shortfall in the other systems:

- In background noise where the auditory signal is compromised, we look more intently (visual) at the face (Sumby & Pollack, 1954)

- If someone coughs and it masks a word, we can fill in the missing word (cognitive) without even being aware of its absence (Warren, 1970; Warren & Obusek, 1971)

- In darkness, we pay more attention to the sounds (auditory) such as creaking floorboards.

If someone isn’t hearing us, we increase our volume, slow down or repeat ourselves (social).

Such multimodal compensation can mask acute and chronic deficiencies in a single domain. So the fact that a conversation “flows” can be misinterpreted as evidence that our hearing is operating as expected. It’s not denial; it’s observation.

Challenge Four: Sneaking Up On You? It’s No Comparison

For most people, change in hearing is gradual with no accompanying symptoms (except, sometimes, tinnitus) to draw attention to it. For someone to perceive any change it has to be possible to make a comparison between two different samplings taken at separate times. If the contrast between the samplings is too small, or the time between those samplings is too widespread, the change won’t be detected.

If we assume for simplicity that pure tone thresholds increase approximately 1dB every year (Lee et al., 2005), for someone to “deny a hearing loss” we are expecting the average person to perceive a daily change of 0.003 dB (1/365). Yet most people need a contrast of at least 1.5 dB before they can detect a difference (Forinash, K), providing the sounds are presented in close succession.

So for someone to detect a change in their own hearing would require them to accurately hold in memory exactly how they heard that same tone presented 18 months earlier, which isn’t realistic.

Challenge Five: Nothing wrong with the volume

Many hearing losses involve predominantly the higher frequencies, so the perception of volume is often subjectively maintained for the most commonly experienced sounds, namely:

- The long term average spectrums for speech (Byrne et al., 1994) and singing (Monson et al., 2012), which contains more energy in the frequencies below 1000Hz.

- Many environmental noises, which tend to fall in the lower register, such as traffic and household appliances.

Furthermore the perception of loud sounds is normally maintained in sensorineural hearing loss, and even increased through abnormal loudness growth, leading to the perception that one’s hearing is “too good, so why would I need amplification?”

Conclusions: Using Observation to Combat Denial

Once we recognise that the problem is not primarily denial but observation we can begin formulating a practical solution. It becomes clear that for someone to recognise change in their own hearing they need:

- A baseline sampling of their hearing that can remain as a static measurement for future comparisons.

- Routine monitoring at fixed time intervals that can be compared to the baseline.

Without these two things people will wait until they notice a change, which delays action. The exception, of course, is hearing that changes more rapidly. We will address both these issues below.

Part 2: Implications of the Difficulty in Perceiving Changes in Hearing

This inability to perceive changes in hearing has some important implications:

1: Lack of Evidence Decreases Action

People are often unaware of changes in their own hearing unless they are presented with evidence that provides them with a credible comparison between what they manifestly hear and what they are expected to hear. This is what HHPs misinterpret as denial.

Ironically “denial” can then later emerge as the result of sustained accusations of denial by HHPs and family. Work by Tomala et al. (2002) on attitude certainty has shown that if people successfully resist a strong attack on their own belief then it makes them more likely to resist future attacks and act in a way consistent with the original attitude.

Applying this to hearing: if someone “observes” that their hearing is fine and can prove it to themselves when someone criticises their hearing (Principles 1-5 above), once hearing is further reduced and good hearing becomes harder to justify, the earlier strengthening of the belief in response to the criticism, combined with “ego-defence” mechanisms (Katz, 1956; Knight Lapinski et al., 2001), will result in making it harder to convince them of the need to use hearing technology.

2: Finger-Pointing Decreases Action

We are more likely to recognise a change in another person’s hearing than we are in our own: if someone doesn’t hear us, we witness indicators that aren’t available to the person with reduced hearing. These include a) having to increase our efforts in conversational repair, and b) incongruity in their response to us or to environmental signals.

3: Disbelief Decreases Action

Being told by someone else that our own hearing has changed, when we have no available evidence to suggest this, is likely to result in disbelief. The more we maintain this “reality”, the more we will look for—and find—evidence to confirm our conviction (Nickerson, 1998).

And the more we do so, the more those disadvantaged by our reduced hearing will seek to “put us straight”! How we personally respond to their challenge will depend on a variety of factors, such as cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957), which has the potential to further delay action.

Implication 4: Mildness Decreases Action

Those with milder hearing loss are less likely to perceive any reduction in their hearing ability because:

- Their visual, cognitive and social systems will find it easier to compensate effectively for the shortfall in auditory information, thus maintaining the overall gestalt and impression that “everything’s as expected”.

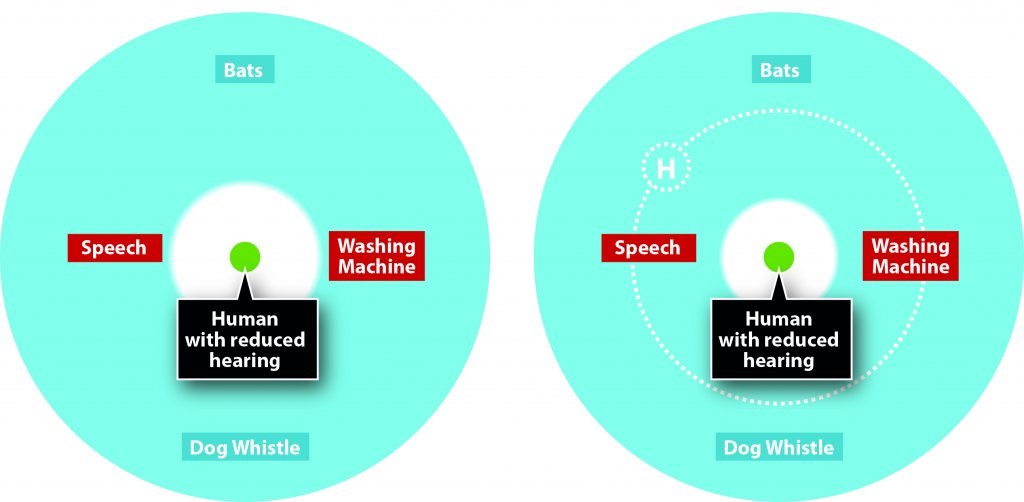

- There will be fewer “events” occurring in their everyday listening experience that present the necessary opportunities required for a comparison with expected hearing. For example, someone with a milder reduction will hear the washing machine, whereas someone with a moderate hearing loss may not. In the first case the noise of the washing machine matches expectations so no comparison, in the second case it doesn’t match and a comparison is triggered—assuming someone remembers what a washing machine should sound like and doesn’t assume that modern technology has developed silent washing!

- The sounds they do hear will offer evidence that they are hearing as expected (Principle 5).

5: Isolation Decreases Action

People who live alone are likely to encounter fewer opportunities for comparison of their hearing and are therefore less likely to notice change, so the need for amplification will be harder to recognise, delaying appropriate action. Furthermore, motivating factors for taking action will be reduced without the ‘encouragement’ from communication partners.

To compound matters, socialising may be less enjoyable due to the stark contrast between their “quiet world at home” and the “noisy world outside”. There is therefore an increased risk of social isolation and/or loneliness, and subsequently a higher risk for depression (Golden et al., 2009), dementia (Holwerda et al., 2014; Wilson et al., 2007) and even increased mortality (Steptoe et al., 2013; Cacioppo et al., 2011; Contrera et al., 2015).

It should be noted that 33% of Baby Boomers are unmarried and that most unmarried Boomers live alone (Lin & Brown, 2012). This should be sounding alarm bells to our Profession.

6: Delayed Intervention Decreases Action

If someone’s hearing range has “always” been reduced (e.g. congenital, acquired in early childhood, longstanding gradual acquired), they are less likely to perceive reduced hearing as they have no remembered experience to compare it with.

7: Rapid Change Increases Action

Hearing that changes significantly enough over a short enough period of time is more likely to be noticed, and salience will be increased where a direct comparison is available, such as unilateral hearing loss (bilateral comparison) or sudden hearing loss (daily comparison).

8: Fluctuations Harder to Detect when Hearing is Worse

Fluctuating hearing loss may be imperceptible to an individual if their thresholds are elevated to the extent where they have no direct environmental or cognitive comparison available (see Figure 2). For example, if their better thresholds are already elevated to the point that static environmental sounds are already outside of their hearing range, these can’t be used as the initial sampling. When their hearing is then further reduced during fluctuation, they have no prior experience to compare the lower thresholds with. In such case, self-reported fluctuating hearing loss may be impossible and might only become manifest once hearing technology is fitted. Even then the fluctuation may be mistaken for variable performance of the hearing device (Lassiter et al., 2002; McArthur, 1980, 1981).

Figure 2. With a fluctuating hearing loss the thresholds transition between two points. If environmental sounds and speech are already falling below the threshold of hearing at the better hearing point (left), then someone will be unable to notice the fluctuation (left diagram), just as they wouldn’t be able to detect if a dog whistle was louder or quieter. The fluctuation may only become evident once hearing technology (H) is fitted, which then extends the hearing range to encompass the previously inaccessible sounds. Now a comparison becomes possible, but the fluctuation in hearing may be mistaken for fluctuation in the performance of the technology.

Part 3: Implications for Hearing Assessments and Adoption of Hearing Technology

1: Action Trigger Cannot Depend On Self-Recognised Hearing Loss

If the primary motivation for getting hearing checked is because people notice a problem with their hearing, then the majority are unlikely to do so as most people simply don’t have the capability to detect the change. This applies regardless of whether a hearing check is with a doctor, a hearing healthcare professional, or using a SmartPhone app.

For example, what would be the motivation for downloading an app for checking our own hearing? Or taking time out of a busy schedule to leave what we are currently doing to visit a website that has an online hearing check? Curiosity? Perhaps. But this cannot be expected of the vast majority of society who don’t share our professional interest in hearing. We need something more: people must be given some other reason to get their hearing checked. And telling people they are in denial is not the answer.

It is interesting to note that in the UK 63% of people with self-reported hearing loss say that they will begin using hearing technology “when their hearing gets worse” (EuroTrak 2012, 2015). In other words, people are looking for a trigger that, in most cases, won’t exist. It’s equivalent to saying that we’ll only answer the door if the doorbell rings, but not owning a doorbell! It doesn’t mean nobody’s come to our door; it simply means we don’t have the capability to detect it.

It should also be highlighted that whilst the promotion of PSAPs may be seen by some as one way to make hearing technology accessible to more people (whatever its other advantages/disadvantages may be), their use still relies on people actually noticing a change in their hearing, and as we saw earlier this is less likely for people with milder hearing loss, which is where PSAPs are positioned. PSAPs are therefore unlikely to have a significant impact on increasing the overall adoption rate of hearing technology for factors other than affordability.

2: Action Resulting from Noticeable Change is a Red-Flag

When change is noticeable it will increase the likelihood of seeking some form of intervention (e.g. professional advice, traditional hearing technology, PSAPs).

But as we saw above, noticeable change is the exception, rather than the norm. It usually means:

- Either a perceptible contrast has developed (e.g. sudden/rapid onset, or asymmetry), which usually indicates an underlying referable condition.

- Or that reduction in hearing has already become severe enough, which means that a delay in intervention has already taken place.

(It should be stated that the absence of noticeable change does not exclude the possibility of an underlying referable condition (e.g. otosclerosis), nor does it mean that someone’s hearing has not yet become ‘severe enough’ to warrant intervention.)

Noticeable change has important consequences for the advice we give the public. If we say that bypassing a trained hearing expert (e.g. “self-screening” or “using a PSAP is sufficient”) is acceptable behaviour for people who notice changes in their hearing, then we are increasing the risk to their health and well being, unless:

- a. We have a robust method for ruling out the possibility of an underlying condition.

- b. We have evidence that non-involvement of a hearing healthcare professional in the longer term management of “easier-to-notice” hearing loss is as effective for individuals and society as the involvement of a professional following best-practice protocols.

Consider the Following Scenario

Someone lies with their head on one side, one ear pressed into the pillow. They then try it with the opposite ear, and notice a clear difference in environmental sounds. This could be a sign of an asymmetry. They have neither the equipment nor training to know the degree or cause of the asymmetry – only that they’re not hearing as well.

If the public advice is “if you notice problems with your hearing, you can get an over-the-counter PSAP or download an app”, this is more affordable and easier than arranging to see an appropriate specialist. They try it, it alleviates the effects of the hearing loss enough to dampen the motivation to take action. Meanwhile the underlying condition worsens (e.g. a growth) or becomes less susceptible to reversal (e.g. sudden sensorineural hearing loss).

Part 4: Implications for Hearing Care Professionals and Policy Makers

Action Point 1: Shift Your Frame from “Denial” To Observation

First and foremost, we must stop telling ourselves that people are in denial and begin seeing this through the eyes of the people we serve: as observation. Their observation may be “wrong” compared to how we see things—and how their family see things—but telling someone they are wrong goes against every principle of effective persuasion and is likely to increase resistance. Furthermore, it risks damaging a person’s self-identity and self-esteem, and that makes the rehabilitation process far harder (see Steele, 1988).

Instead, when we see it as observation, and we look at what people need in order to recognise a change in their hearing, we can begin designing our services accordingly. We conduct our appointments differently. We encounter less resistance.

Our goal is not to convince someone they have hearing loss. Instead it is to enable them to bring sound back within their hearing range so they don’t lose out. This immediately better aligns with their own goals, because people are motivated to avoid loss and seek gain (Updegraff et al., 2007; Kahneman et al., 1991).

Action Point 2: Don’t Wait for People to Notice a Problem

It is absurd for us to wait until people recognise a change in their own hearing, then wonder why more people aren’t using hearing technology!

The detection of a reduction in hearing obviously precedes the use of hearing technology, yet most hearing care provision focus solely on hearing aids, and many hearing care providers (and manufacturers) see hearing checks as being a “waste of time” or a failure unless it directly leads to a fitting. We have been putting the cart before the horse, then wondering why haven’t moved forward in increasing the uptake of hearing technology!

As we saw earlier, to detect change we need at least two samplings: a baseline, and a deviation from that baseline. People often don’t have that luxury “in the real world” because hearing changes gradually. It’s up to the Profession to provide it for them:

- Offer a baseline hearing check so people have a starting point.

- Routinely monitor it every 5 years (if they are hearing as expected), or more regularly if there is a reduction.

In the first case (a) we attract two types of people: those with good hearing, and those who think they have good hearing.

In the past these individuals haven’t visited a hearing healthcare professional because they believed their hearing wasn’t “bad enough” to warrant it, because the focus was on poor hearing. Yet these are many of the individuals who would benefit from hearing technology but haven’t acted – which means by offering a baseline we begin tapping into some of those 3 out 4 of people we currently leave behind (Kochkin, 2009).

Additionally, the individuals who have good hearing are:

- Being exposed to hearing healthcare, which builds trust and liking (Zajonc, 1968)

- Increasing the importance of their hearing through their actions (Bem, 1972)

- Educating themselves about auditory wellbeing and updating social attitudes to hearing technology

- Becoming more likely to be messengers to others in society about the benefits of hearing care (“keeping hearing at its best”).

- Creating “social proof” that encourages others to have their hearing checked, including those who would benefit from hearing technology (Cialdini & Trost, 1998; Cialdini, 2009).

- Helping to offset the overheads of running a practice (unless the hearing check is free) by spreading the cost over a greater number of individuals, so that the cost of hearing technology becomes more affordable.

In the second case (b), routine monitoring establishes a habit that involves a qualified professional, like a dentist or optician. More importantly we are providing a comparison for people, which as we’ve seen is essential for recognising change. If they come the first year with a slight reduction in hearing, that wouldn’t measurably benefit from hearing technology, but on the re-assessment the hearing has changed, the contrast between the two audiograms will help to persuade someone to “bring sounds back within their hearing range” (i.e. prevention of future loss).

When done properly, offering baseline hearing checks and routine monitoring “throughout life” will do more to increase the uptake of hearing technology and prevent noise-induced hearing loss than any other measure. (The other two most important measures being affordability/accessibility and the avoidance of stereotyping.)

Action Point 3: Make Hearing Checks about Wellbeing, Not Loss

We saw earlier that we have to give people a motivation for getting their hearing checked that doesn’t rely on noticing a change in hearing. Our message must present hearing checks as a normal part of health and wellbeing, rather than for singling out ‘deviance’ (Goffman, 1963).

So our message must not focus on a specific demographic (e.g. the over 50s or over 60s; the “hearing impaired”). Instead it must be seen as applying to everyone (i.e. ageless) and “normal”— otherwise we stigmatise those who respond.

This means shifting the meaning of the hearing assessment from “detecting hearing loss” to “maintaining maximal hearing” (and the implications of this). Note that we are shifting the meaning of hearing care away from trying to “fix/correct/treat the condition of the ear” and to maintaining the auditory connection between the external (social) world and the internal (psychological) world, i.e. psychosocial wellbeing. Such a message has universal (and topical) appeal: it means being all that you can be (Maslow, 1943; Deci & Ryan, 2002), and hearing plays an integral role in this (for reasons that would require a separate article).

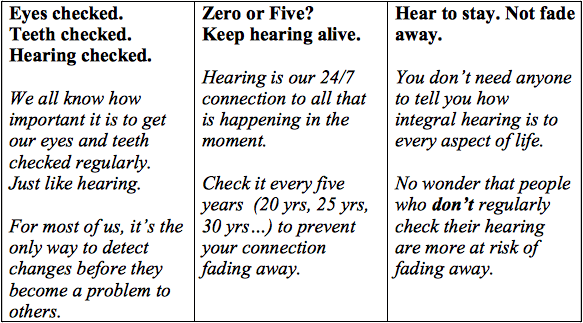

We finish with three simple examples of how we can present such a message:

Please feel free to use these, monitor the response, and improve on them to increase your response.

Conclusions

Our traditional approach of labelling people as “in denial” clearly hasn’t been working, as evidenced by the minority adoption of hearing technology and the resistance experienced by HHPs in the initial appointment.

We have a choice. We can continue as we always have done, looking for a future miracle in societal attitude change that will never happen. Or we can start learning from the social sciences which have been addressing issues like our own for well over a hundred years (Briñol & Petty, 2012).

For people to change their behaviour, they need the capability, motivation and opportunity to do so (Michie et al., 2011).

If the target behaviour is to use hearing technology, they first need to recognise the need for the technology. But we have seen that most people don’t have that capability because it’s virtually impossible to notice changes in one’s own hearing. So we must give them the capability, and the most logical way is by offering a baseline hearing check (the initial sampling) followed by routine hearing checks throughout life (comparative samplings).

We must then give them the motivation, and this must align with people’s own goals and self-concept, otherwise we create resistance – which is what we have been doing all these years with our accusations of denial. So we reframe the hearing check from the detection of loss (with its concomitant stigmatisation of the minority) to the maintenance of wellbeing through maximal hearing.

Finally, we must give people the opportunity to have their hearing checked—and not just when they suspect a need for hearing technology. Otherwise we miss all those who could be benefiting but don’t have the capability to recognise it.

And isn’t that where the increased uptake must come from?

References

Bem, D.J. (1972). Self-Perception Theory . In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances

in experimental social psychology (Vol. 6, pp. 1-62). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Briñol, P., & Petty, R. E. (2012). The history of attitudes and persuasion research. In A. Kruglanski & W. Stroebe (Eds.), Handbook of the history of social psychology (pp. 285-320). New York: Psychology Press.

Brungart, D. S., Simpson, B. D., Ericson, M. A., & Scott, K. R. (2001). Informational and energetic masking effects in the perception of multiple simultaneous talkers. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 110(5), 2527-2538.

Byrne, D., Dillon, H., Tran, K., Arlinger, S., Wilbraham, K., Cox, R., ... & Ludvigsen, C. (1994). An international comparison of long‐term average speech spectra. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 96(4), 2108-2120.

Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., Norman, G. J., & Berntson, G. G. (2011). Social isolation. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1231(1), 17-22.

Cialdini, R.B. & Trost, M.R. (1998). Social influence: Social norms, conformity, and

compliance. In D.T. Gilbert, S.T. Fiske & G. Lindzey (Eds), The handbook of social

psychology (4th edn, Volume 2, pp. 151-192).

Cialdini, R.B. (2009). Influence: Science and Practice (5th Edition), Chapter 4.

Contrera KJ, Betz J, Genther DJ, Lin FR. Association of Hearing Impairment and Mortality in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Published online September 24, 2015. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2015.1762.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2002). Handbook of self-determination research.

EuroTrak 2015, 2012

Festinger, L. (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson.

Forinash, K. An Interactive eBook on the Physics of Sound. https://soundphysics.ius.edu/?page_id=914 Accessed 26.09.2015

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity, Chapter 2 . Simon & Schuster.

Golden, J., Conroy, R. M., Bruce, I., Denihan, A., Greene, E., Kirby, M., & Lawlor, B. A. (2009). Loneliness, social support networks, mood and wellbeing in community‐dwelling elderly. International journal of geriatric psychiatry, 24(7), 694-700.

Hayashi, M., Raymond, G., & Sidnell, J. (2013). Conversational repair and human understanding (Vol. 30). Cambridge University Press.

Holwerda, T. J., Deeg, D. J., Beekman, A. T., van Tilburg, T. G., Stek, M. L., Jonker, C., & Schoevers, R. A. (2014). Feelings of loneliness, but not social isolation, predict dementia onset: results from the Amsterdam Study of the Elderly (AMSTEL). Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 85(2), 135-142.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., Thaler, R. H., (1991). The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion,

and Status Quo Bias . The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 5, No. 1. (Winter, 1991),

pp. 193-206.

Katz, D., Sarnoff, I., & McClintock, C. (1956). Ego-defense and attitude change. Human Relations.

Knight Lapinski, M., & Boster, F. J. (2001). Modeling the ego-defensive function of attitudes. Communication Monographs, 68(3), 314-324.

Knowles, E. S., & Linn, J. A. (Eds.). (2004). Resistance and persuasion. Psychology Press.

Kochkin, S. (2007). MarkeTrak VII: Obstacles to adult non‐user adoption of hearing aids. The Hearing Journal, 60(4), 24-51.

Kochkin, S. (2009). MarkeTrak VIII: 25-year trends in the hearing health market. Hearing Review, 16(11), 12-31.

Kochkin, S. (2014). A Comparison of Consumer Satisfaction, Subjective Benefit, and Quality of Life Changes Associated with Traditional and Direct-mail Hearing Aid Use. Hearing Review, 21(1), 16-26.

Lakatos, P., Chen, C. M., O’Connell, M. N., Mills, A. & Schroeder, C. E. Neuronal oscillations and multisensory interaction in primary auditory cortex. Neuron 53, 279–292 (2007).

Lassiter, G. D., Geers, A. L., Munhall, P. J., Ploutz-Snyder, R. J., & Breitenbecher, D. L. (2002). Illusory causation: Why it occurs. Psychological Science, 299-305.

Lee, F. S., Matthews, L. J., Dubno, J. R., & Mills, J. H. (2005). Longitudinal study of pure-tone thresholds in older persons. Ear and hearing, 26(1), 1-11.

Lin, I-Fen and Susan L. Brown. 2012. “Unmarried Boomers Confront Old Age: A National Portrait.” The Gerontologist, 52(2): 153-165.

Lind, C., Hickson, L., & Erber, N. P. (2004). Conversation repair and acquired hearing impairment: A preliminary quantitative clinical study.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological review, 50(4), 370.

Mattys, S. L., Davis, M. H., Bradlow, A. R., & Scott, S. K. (2012). Speech recognition in adverse conditions: A review. Language and Cognitive Processes, 27(7-8), 953-978.

McArthur, L.Z. (1980). Illusory causation and illusory correlation: Two epistemological

accounts. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 6, 507–519.

McArthur, L.Z. (1981). What grabs you? The role of attention in impression formation and causal attribution. In E.T. Higgins, C.P. Herman, & M.P. Zanna (Eds.), Social cognition: The Ontario symposium (Vol. 1, pp. 201–241). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

McGurk, H. & MacDonald, J. Hearing lips and seeing voices. Nature 264, 746–748 (1976).

Michie, S., van Stralen, M. M., & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: a

new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions.

Implementation Science, 6(1), 42.

Monson, B. B., Lotto, A. J., & Story, B. H. (2012). Analysis of high-frequency energy in long-term average spectra of singing, speech, and voiceless fricatives. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 132(3), 1754-1764.

Mundt, J. C., Snyder, P. J., Cannizzaro, M. S., Chappie, K., & Geralts, D. S. (2007). Voice acoustic measures of depression severity and treatment response collected via interactive voice response (IVR) technology. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 20(1), 50–64. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroling.2006.04.001

Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of general psychology, 2(2), 175.

Perloff, R. M. (2010). The dynamics of persuasion: communication and attitudes in the twenty-first century. Routledge.

Sams, M. et al. Seeing speech: visual information from lip movements modifies activity in the human auditory cortex. Neurosci. Lett. 127, 141–145 (1991).

Steele, C. M. (1988). The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self. Advances in experimental social psychology, 21(2), 261-302.

Steptoe, A., Shankar, A., Demakakos, P., & Wardle, J. (2013). Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(15), 5797-5801.

Stein, B. E., & Stanford, T. R. (2008). Multisensory integration: current issues from the perspective of the single neuron. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9(4), 255-266.

Sumby, W. H. & Pollack, I. Visual contribution to speech intelligibility in noise. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 26, 212–215 (1954).

Tormala, Z. L., & Petty, R. E. (2002). What doesn't kill me makes me stronger: the effects of resisting persuasion on attitude certainty. Journal of personality and social psychology, 83(6), 1298.

Updegraff, J. A., Sherman, D. K., Luyster, F. S., & Mann, T. L. (2007). Understanding how tailored communications work: The effects of message quality and congruency on perceptions of health messages. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43, 248-256.

Von Uexküll, J. (2014). Umwelt und innenwelt der tiere. Springer-Verlag.

Warren, R. M. (1970). Perceptual restoration of missing speech sounds. Science, 167(3917), 392-393.

Warren, R. M., & Obusek, C. J. (1971). Speech perception and phonemic restorations. Perception & Psychophysics, 9(3), 358-362.

Wilson, R. S., Krueger, K. R., Arnold, S. E., Schneider, J. A., Kelly, J. F., Barnes, L. L., & Bennett, D. A. (2007). Loneliness and risk of Alzheimer disease. Archives of general psychiatry, 64(2), 234-240.

Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of personality and social psychology, 9(2p2), 1.

Zekveld, A. A., Heslenfeld, D. J., Festen, J. M., & Schoonhoven, R. (2006). Top–down and bottom–up processes in speech comprehension. NeuroImage, 32(4), 1826-1836.

Zimbardo, P. G., Pilkonis, P., & Norwood, R. (1977). The Silent Prison of Shyness (No. TR-Z-17). Stanford Univ Ca Dept of Psychology.