Dusting Off Some Gems from the Audiologists’ Desk Reference Books

Back in the mid-1990s, the two of us were doing workshops together at Vanderbilt University. After one of these workshops, we got to talking about the fact that we were always getting asked where one could find specific information related to hearing science, diagnostic testing, hearing aid fitting, and audiology in general (having Google find it for you wasn’t an option in those days). Wouldn’t it be nice if there were just one book, filled with charts, graphs, tables, and figures that would serve as single source for professors, researchers, clinicians and even students—The Audiologists’ Desk Reference or ADR was born—if our memory is correct, at Bosco’s Brewery, our favorite watering hole at the time.

Jay took the lead as we decided that the book’s first part would focus on diagnostics, and he had already done considerable writing on aural immittance, ABRs and otoacoustic emissions. With the help of some eager students going through other books and journal articles, it wasn’t long before we had amassed a large collection of relevant information. So much so that we realized that our little project needed to be expanded to two books, the ADR Volumes I and II.

All the content we collected was shipped off to Singular Publishing (now Plural) for printing. They put it together quickly and Volume I was published a few months later in 1997—all 900+ pages! The even longer Volume II … 1006 pages … was published in early 1998. We were impressed by the heftiness of the ADR Volume I, but when we started looking through the book page by page, we noticed something we hadn’t thought through carefully. The varied material was laid out orderly relative to the topic. As a result, a chart that only filled ¼ of the page might be followed by a chart that filled an entire page so ¾ of the first page was left blank. This happened a lot. Not only did this look goofy, but we started to get some friendly ribbing from our colleagues for publishing a 900-page book with only 600 pages of content. Although it wasn’t quite that bad, and we were tempted to blame the publisher, the self-proclaimed book critics did have a point.

We knew the same thing would happen for Volume II, so we developed a plan. Once everything was laid out, and ready for printing, we would have the publisher, Singular send it to us. We would then go page by page, and any page that was not at least 2/3 full, we would add content to mostly fill the page. If two people worked on such a project today, it would likely involve several Zoom meetings and many emails with many attachments. But not so in the 1990s. The plan was that Gus would travel to Nashville, and stay at Jay’s house for a week during Jay’s summer break. This conveniently coincided with the same time that Jay was developing considerable skills in home brewing!

In many cases, we could think of something to fill the page related to the content on the top—but not always. We decided to come up with the headings such as “Audioid” and “Did You Know.” We would then fill the box with something at least loosely related to audiology. We had such a good time doing all these tidbits, that we decided to add a chapter to the book titled “Hard to find audiology gems.”

All this takes us to the present article. Given that our ADR books are out of print, and some of you readers weren’t thinking much about audiology in the 1990s, we thought we’d bring back some of our audiology gems, and maybe even a few Audioids.

The Queen, Presidents, and Hearing Aids

When someone famous is spotted wearing hearing aids (or even one), it’s always a heyday for the press—maybe more so than it should be. Many of you probably recall back on Sunday, January 12, 2020, when the British newspaper Daily Mail photographed Queen Elizabeth II wearing a red and beige CIC hearing aid (partially hidden by her hair) on her way to church service—the first official Queenly “hearing aid sighting.” The story was picked up by news outlets worldwide, and of course, also was the talk of audiology forums, where the main focus was trying to identify the brand. Of course, U.S. Presidents and hearing aids also have warranted extensive media attention. We covered some of this in ADR Volume II.

Ronald Reagan. On September 7th, 1983, a White House spokesman announced at a press conference that President Reagan was wearing hearing aids, although at a meeting that day, he only wore one (small custom instrument) in his right ear. The news was reported on the 1st page of the New York Times. After the President’s acknowledgement of hearing aid use, unit sales soared by 30% in the fourth quarter of 1983.

Bill Clinton. On October 3rd, 1997, CNN reported that President Clinton was fitted for hearing aids as part of his annual physical examination. By the 10th of October, rumors on the Internet had the order arriving at the offices of five different hearing aid manufacturers! There hasn’t been much talk of his hearing aid use since, although Clinton has been active with the Starkey Hearing Foundation.

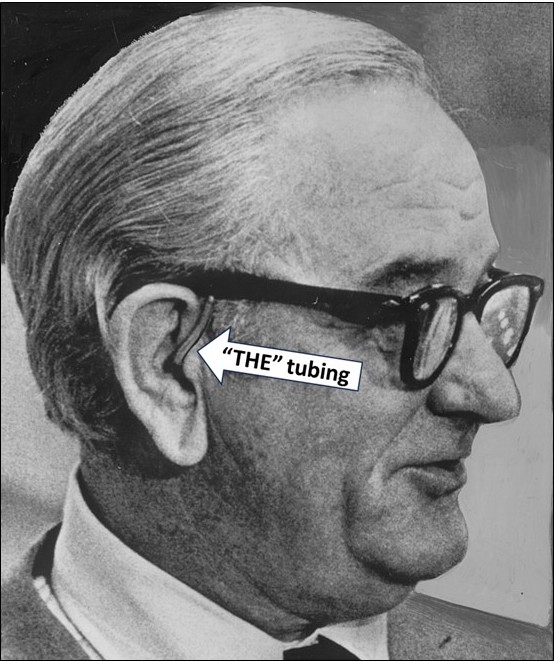

Lyndon Johnson. This event didn’t make CNN or the front page of any newspaper, but it should of. If the fall of 1972, former President Lyndon Johnson was a patient at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio Texas. Late one afternoon, his aide brought his Sonotone CROS hearing aid (wired through a pair of black horned-rimmed glasses) to the audiology clinic for repair—Mr. Johnson was complaining that it didn’t have enough power. (Note: Johnson had a bilateral symmetrical high-frequency loss, but bilateral fittings were not common then. However, the CROS-fitting for this type of loss was common, as more gain-before-feedback could be obtained for an open fitting than if fitted unilaterally).

The audiologist, a dashing young Lieutenant, quickly determined that the tubing needed to be replaced (it was a tube-only, no-mold fitting). It was old, hard, cracked and very yellowed—Johnson was a heavy smoker. The old tubing was cut off the output spout on the glasses’ temple. We didn’t have pre-formed #13 tubing in those days, so using the old tubing as a guide, the wire of a paper clip was placed inside the new tubing and it was carefully bent to mimic its predecessor. Once the correct form was obtained, the tubing was heated with a hair dryer, then immediately dumped in ice water, and presto—when the wire was removed a perfect shape stayed in place—a procedure the savvy Lieutenant had done many times before. The aid was turned on, and a welcome 100+ dB of feedback was observed.

The brimming Lieutenant gleefully took the repaired hearing aid to Johnson’s VIP suite that evening for a fitting. While waiting for official permission to enter the former-President’s sitting room, he heard a lot of loud discussions, bordering on arguments—Johnson was known to be a bit moody. The aide informed the Lieutenant that there would be no fitting, to just leave the hearing aid.

At 7:00 the next morning when the young Lieutenant arrived to open the clinic, the aide was waiting outside the door. “The President is very upset; he wants his old tubing back.” This of course made no sense, as it was the source of the problem, but . . . he was a former President. The Lieutenant went to his office to see if perhaps the garbage had not been emptied. It had been. Lyndon Johnson passed away a few months later.

Audiologic DNA and UFO Sightings

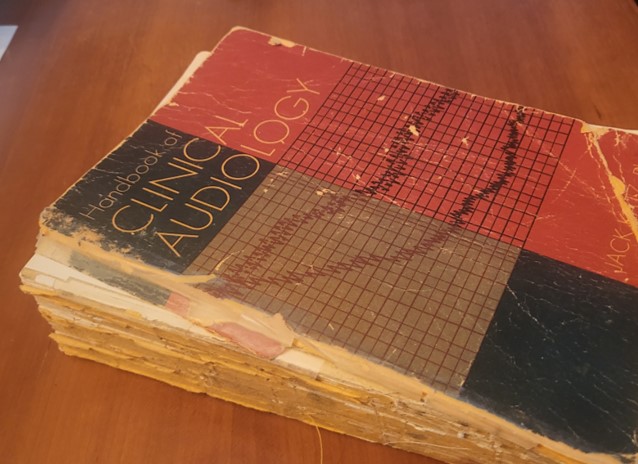

It’s often been said that the DNA of an audiologist can be determined by what edition of the Jack Katz Handbook was popular at the time of their graduate training. As you might guess, we’re both 1st Edition guys—the one with the Type IV Bekesy tracing on the cover. There are two chapters in that book that we remember the best—the David Lilly chapter on acoustic impedance, which was nearly impossible to understand, and the chapter on air conduction testing by audiologist David S. Green (1926-2019). What made Green’s chapter memorable, was the section on UFOs—Useful Finger Observations—where he cleverly tells us about the six different types to look for. It clearly pointed out to us, that one could be entertaining, and make a teaching point, all at the same time. In the ADR Volume II, we reprinted Green’s entire UFO section, which we encourage you check out (maybe in a forthcoming ADR Revival eBook). For now, we’ll paraphrase his descriptions just to give you the flavor.

Green’s intro: Each category has its own distinct symptomatology; each has its own test profile and each is associated with characteristic pathology. Before the search for UFOs can begin, the patient must be instructed to raise his index finger when he hears a tone, and to lower it as soon as he is no longer hearing it.

The Halfup Finger. The Halfup Finger reflects uncertainty in the subject’s mind regarding the presence of tonal signals and occurs when there is a normal sensorineural level. Unlike the False Alarm Finger (described later), which also shows uncertainty regarding the presence of test tones, the Halfup Finger is seldom in error. From its inimitable semi-erect slouch, it unerringly fingers its own true threshold.

The Allernone Finger. With impressive sure-fingeredness, the Allernone Finger makes unhesitating choices about the audibility of the test tones. Lest one become overly impressed with this finger feat, be warned that the pseudo-alertness may be related to a cochlear lesion and the recruitment associated with such a lesion.

The Body Finger. This finger is usually ankylosed to a worn nervous system which has lost some it’s ability to selectively inhibit motor responses. Thus, when the Body Finger is induced to respond, a response may also be expected from multiple other extremities. Sightings are frequently made with geriatric patients.

The Malingafingers. Clinicians should be particularly alert to sightings of the “delayed reaction” finger, and the finger known as the “inflation index,” two of the more common Malingafingers. On the one hand, the “delayed reaction” finger can be recognized by the fact that it does not respond unless the tone remains on for longer than usual. The “inflation index” finger, on the same hand, can be recognized by the fact that it only will respond to progressively greater increments in tonal intensity.

The Falsealarm Finger. The Falsealarm Finger is usually attached to an individual who is very difficult to test. Its action is frequently independent of the action of the tester, and often marked by five or six positive finger responses in the interval between placement of the earphones and the initial presentation of the tones. The Falsealarm Finger is moved by tinnitus, or the suggestibility associated with certain pre- and postoperative anxieties.

The Tired Finger. Tired finger may be confused with Dumb Finger by the beginning clinician. Dumb Finger is a category of questionable authenticity since it discourages the pursuit of more valid diagnostic UFO categories. After repeated instruction, the Tired Finger still responds initially, but then drops before the tone is discontinued. Tired Finger might be the first sign of a retrocochlear lesion. Occasionally, the Tired Finger may waver, but not fall.

The beginning audiologist is encouraged to waste no time in learning to assign finger responses to their appropriate categories. This sense of urgency is dictated by the fact that diagnostic opportunity may knock but once for a given finger.

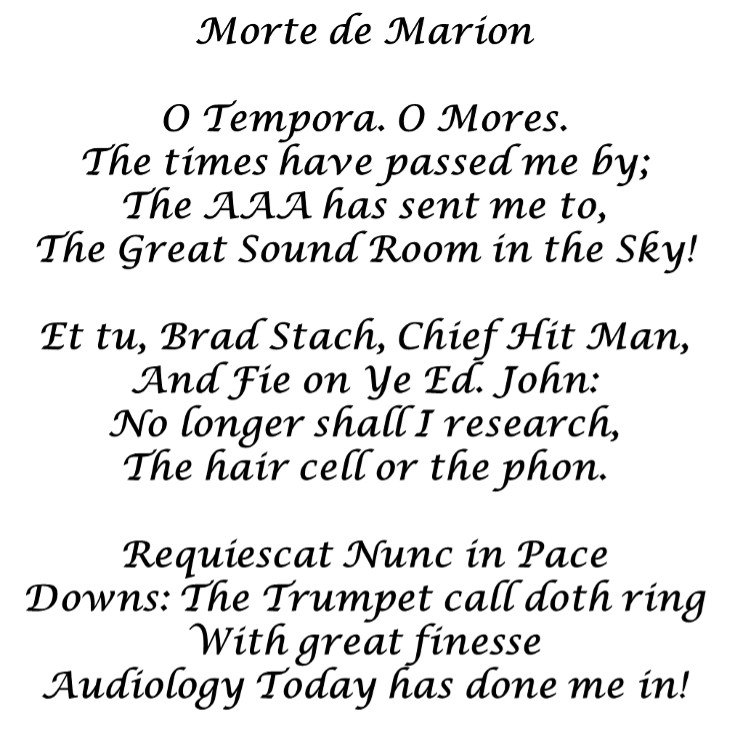

Morte de Marion

In 1992, the American Academy of Audiology (AAA) had reached a sizable membership, and John Jacobson, Editor of Audiology Today at the time, thought it would be appropriate to publish some demographics regarding the membership. One of the charts he showed was the distribution of the members’ ages. Interestingly, there were no members over the age of 70. Or was there? John’s chart caught the eye of one Marion Downs, an AAA member over 70. Really, if you’re going to leave someone out, do you want it to be one of the most well-known audiologists in the world? As you might guess, this oversight prompted Marion to write a Letter to the Editor, in the form of an entertaining poem, titled Morte de Marion. John, of course, published it in the next edition of Audiology Today.

Fortunately for the profession of audiology, Marion enjoyed life for at least another 25 years after writing the poem. She died in 2014 at the age of 100, seven years after publishing her first single-author book … Shut Up and Live! (You Know How): A 93-Year-Old’s Guide to Living to a Ripe Old Age.

Acronym Jim

The AAA was founded in the late 1980s, largely thanks to the efforts of world-renown audiologist James Jerger. Fittingly, Jim served as the first president. In those early days of the AAA, meetings were from Thursday to Sunday, with a big semi-formal banquet on Saturday night. There always was a fun program, with Jerry Northern leading the way with his sidekick Chuck Berlin on the piano, playing bits of songs that may or may not relate to what Jerry was saying. There was reason for a big celebration in 1993, as the organization was celebrating its 5th birthday. We had rapidly grown from a membership of 32 to several thousand, and were celebrating our freedom from the ASHA. Chuck Berlin wrote a special Jim Jerger song in honour of the fellow who got it all started. Now, most everyone in the audience had heard Chuck play the piano at one time or another; he was very accomplished, performed informally at most all meetings or wherever there was a piano, and when back at his New Orleans’ home, often sat-in with bands on Bourbon Street. What made this night special was that he also sang the song. No one had ever heard Chuck sing before! You younger readers might not recognize all the acronyms in Acronym Jim, but take our word for it, they all are Jergerisms. If you want to sing along, it goes to the music of “It had to be you.”

It’s Acronym Jim, Jim Jerger . . . that’s him

He took us from SPAR, to ABR, through SISI and SPIN

Then to SSI, he’s that kind of guy

First ICM, then CCM, and now the 3-As we’re in.

He’s acronym’s Pal, that’s why we have SAL

And SWAMI and RASP, and Listening Tasks, with Crocket et al.

But nobody else gave us this list

Which is why we all can’t resist

Old Acronym Jim, Jim Jerger . . . that’s him

A jewel in our midst!

Did you know . . .

As we mentioned earlier, to fill some ADR semi-blank pages, we tossed in several “Did you knows.” Here are a few of them.

- We’ve all worked with both the Valsalva and Toynbee maneuvers at one time or another, but did you know that Toynbee died due to the Valsalva procedure. Seems it’s not a good idea to try to cure your tinnitus by inhaling a combination of chloroform and prussic acid!

- In 1960 Danavox introduced a very small body aid (by 1960 standards)—not much bigger than a thumb. The product’s name? Thumbalina!

- One of the first probe-mic systems (mid-1980s) was from Bosch, but only stayed on the market for two years—perhaps the name “Earton Invivo” was a factor!

- The first records of a custom earmolds are those from a New York Dentist in the 1920s. The material? Plaster-of-Paris!

- Most all audiologists are familiar with E-A-R hearing protection devices, but how many know the words behind the acronym? Energy Absorbing Resin (of course).

- TDH earphones use Bunna-S rubber (you’re right, there’s really no good reason to know this, but it is a fun word to say to colleagues)

Famous and Infamous Quotes

Both ADRs are filled with quotes: Classical, neo-Classical, Famous and most definitely Infamous. Here are a few of our favorites.

Richard Seewald (1995) on the struggles of “getting the word out” regarding amplification for children: “For whatever reason, the session on amplification for children is scheduled concurrently with a session on otoacoustic emissions. The session on emissions is held in the Grand Ballroom; the session on amplification for children is held in the Riverboat Suite B3, which is adjacent to and no larger than the men’s washroom. Surely, I cannot complain – amplification for children has never filled the Riverboat Suite B3 and the Grand Ballroom has been standing room only.”

David Pascoe (1980) on audibility: “Although it is true that mere detection of a sound does not ensure its recognition, it is even more true, that without detection, the probabilities of correct identification are greatly diminished.”

Jim Jerger (1980) on audiologists’ love affair with monosyllables: “We are, at the moment, becalmed in a windless sea of monosyllables. We can sail further only on the fresh winds of imagination.

Sam Lybarger (1957); this single sentence, 83-word quote was made into a small poster by a prominent hearing aid company, and hung on the wall of many dispensing offices in the 1960s): “A hearing aid is an ultra-small electro-acoustic device that is always too large, that has to faithfully amplify speech a million times without bringing in any noise, that has to work without failure—in a flood of perspiration or a cloud of talcum powder, that one usually puts off buying for 10 years after he needs it because he doesn’t want anyone to know he is hard-of-hearing, but which he can’t do without for 30 minutes when it needs to serviced.” (And an editor’s note- when I first met Mr. Lybarger at an ASHA convention in the 1980s he was standing at the back of the room. I approached him after noticing that he was wearing eye-glass hearing aids. Since I was fascinated with earmold acoustics and he wrote the definitive chapter on earmold acoustics in several of the classic Katz Handbooks, I asked him what he knew that I did not. He said “a lot”… I then skulked away…).

Thomas Edison (who had a significant hearing loss): “I couldn’t hear, for instance, the conversations at the dinner tables of the boarding houses . . . I have no doubt that my nerves are stronger and better today than they would have been if I had heard all the foolish conversation and other meaningless sounds that normal people hear.”

Bob Dylan (1997) on silence and tinnitus: “Sometimes the silence can be like thunder.”

Shakespeare (1608) on speechreading: “Fie, fie upon her. There’s language in her eye, her cheek, her lip. Nay, her foot speaks; her wanton spirits look out, at every joint and motive of her body.”

In Closing

We hope you’ve enjoyed the reprisal of some of the gems from our ADR books. We’ve found that it’s not always easy to recognize an audiology gem when you see or hear it. In general, we rely on the guidance provided by Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart back in 1964: “I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to be embraced . . . and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it.”