The Psychological Dimensions of Hearing Healthcare: Audiology is More Than Just Diagnoses and Devices

Overcoming resistance to wearing hearing aids represents a significant challenge in audiology, stemming from practical concerns about device cost, handling, and aesthetics and deeply rooted in psychological factors. The reluctance often observed among patients to adopt hearing aids, even when clinically advised, can be attributed to a complex interplay of cognitive biases, self-perception issues, and social stigma (McCormack, & Fortnum, 2013; Ekberg, Grenness, & Hickson, 2014). In this paper, I aim to provide some (but not all) of the many factors we interact with daily to help individuals with hearing loss make hearing-positive decisions (for example, getting hearing aids to improve communication).

Noise and Bias

In decision-making, particularly within healthcare, noise, and bias significantly affect judgments and outcomes. Bias is a systematic skew that pulls decisions away from objectively expected or optimal, rooted deeply in a practitioner’s personal experiences, cultural influences, and ingrained habits. For instance, a healthcare provider might consistently lean towards a treatment they believe is superior based on personal success stories, even when evidence suggests otherwise.

Conversely, noise refers to the variability in decisions made under similar circumstances, which ideally should be uniform. This unwanted variability, or noise, manifests when different practitioners deliver divergent diagnoses for the same symptoms presented under identical conditions. This inconsistency can stem from variable levels of expertise, differing interpretations of the same information, or even fluctuating levels of concentration and fatigue among medical staff.

The literature suggests that both elements can detrimentally impact the efficacy of healthcare decision-making (Kahneman., Sibony, & Sunstein, 2021). To comprehend the origins of noise and bias within patient-professional interactions, we must delve into various psychological factors that could underpin these phenomena in healthcare settings. Starting with narratives, we’ll progress to examine potential psychological influences contributing to the presence of noise and bias. Finally, the strength of the therapeutic alliance we establish with our patients, combined with a consistent awareness of the various sources of noise and bias in our clinical decision-making process, is crucial for improving the acceptance of hearing aids and addressing the challenges associated with their adoption in audiology.

Patient Narrative

As a potential patient/client steps into an audiologist’s office, a narrative often unfolds in their mind, woven from anticipation, past experiences, and hope for improved communication abilities (English, 2022). This internal dialogue might include concerns about the potential diagnosis, its implications on their daily life, and expectations for a visit—perhaps a memory of past treatments and their outcomes or anxiety about the testing procedures like speech-in-noise tests. Patients may also reflect on how hearing loss has affected their social interactions and may be considering hearing aids or other interventions that could restore their hearing and a sense of normalcy. This narrative is deeply personal and shapes their perception of care, emphasizing the importance of patient-focused, empathetic approaches in audiology.

Audiologist Narrative

Similarly, when an audiologist meets a new patient for the first time, a narrative begins to unfold in their mind. They carefully observe the patient’s demeanor, listening attentively to the subtle cues in their voice and the explicit concerns they express. The audiologist reflects on the wealth of clinical experience they’ve accumulated, considering the textbook cases and the unique outliers they’ve encountered. As the patient describes their symptoms, the audiologist mentally sifts through possible diagnoses, weighing the likelihood of common conditions against rarer disorders. Simultaneously, they craft a preliminary plan for diagnostic tests and consider potential treatment options. This internal narrative is guided by a deep commitment to restoring or enhancing the patient’s auditory abilities, driven by a blend of empathy, scientific knowledge, and a keen sense of duty to tailor the care to each individual’s needs. This ongoing mental dialogue helps the audiologist navigate the complexities of each case, ensuring they provide the most effective and compassionate care possible.

Various factors contribute to forming narratives for both parties involved (Clark, Garinis, & Konrad-Martin, 2021). In this paper, I aim to transport us back to our undergraduate psychology courses to revisit the concept that all individuals are susceptible to certain psychological pitfalls. These traps can potentially affect our capabilities as patients and professionals to intertwine our narratives to improve patient outcomes effectively.

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias, often considered the mother of all biases, is a psychological phenomenon where individuals tend to favor information that confirms their preexisting beliefs, ignoring evidence that contradicts them (Nickerson, 1998). This bias can significantly influence diagnoses and treatment plans in healthcare decision-making. For example, a doctor might continue to support a favored diagnosis despite new evidence suggesting an alternative or might select tests likely to confirm their initial hypothesis rather than explore other possibilities. This can lead to misdiagnosis or ineffective treatment.

In audiology, confirmation bias can significantly impact patients’ decisions regarding hearing aids. This cognitive bias may lead individuals to prioritize information supporting their beliefs while discounting evidence. For example, a patient who believes that “hearing aids don’t work” might focus exclusively on reviews or testimonials that reinforce this notion, ignoring numerous studies and positive user experiences that demonstrate the effectiveness of hearing aids. This selective attention could deter them from seeking treatment that could improve their quality of life. By only acknowledging negative outcomes, the patient remains unconvinced of the benefits of hearing aids, thus reinforcing their initial skepticism and potentially missing out on a treatment that could significantly enhance their hearing and daily interactions. The reality is that, even in countries where the costs of hearing aids are covered, such as Norway or the United Kingdom, only about 30 to 40% of people who need them are using them. Of course, confirmation bias may have a more subtle and nuanced effect than the cost or the look of a hearing aid; however, it is certainly a factor in hearing uptake and adherence.

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in their capability to execute courses of action necessary to achieve specific goals or tasks. It involves confidence in one’s abilities to confront and effectively manage challenging situations (Bandura, 1977; Holloway & Watson, 2002). Self-efficacy influences patient behavior, treatment adherence, and overall health outcomes in healthcare decision-making. Patients with high self-efficacy are more likely to engage in proactive health behaviors, adhere to medical advice, and persist in facing setbacks. For example, a study by Jerant et al. (2011) found that patients with higher self-efficacy were more likely to adhere to medication regimens and adopt healthier lifestyles, leading to better management of chronic conditions like diabetes. Furthermore, individuals with greater self-efficacy tend to communicate more effectively with healthcare providers, actively participate in shared decision-making processes, and express preferences regarding their treatment options. This empowerment can lead to increased patient satisfaction and improved healthcare outcomes overall.

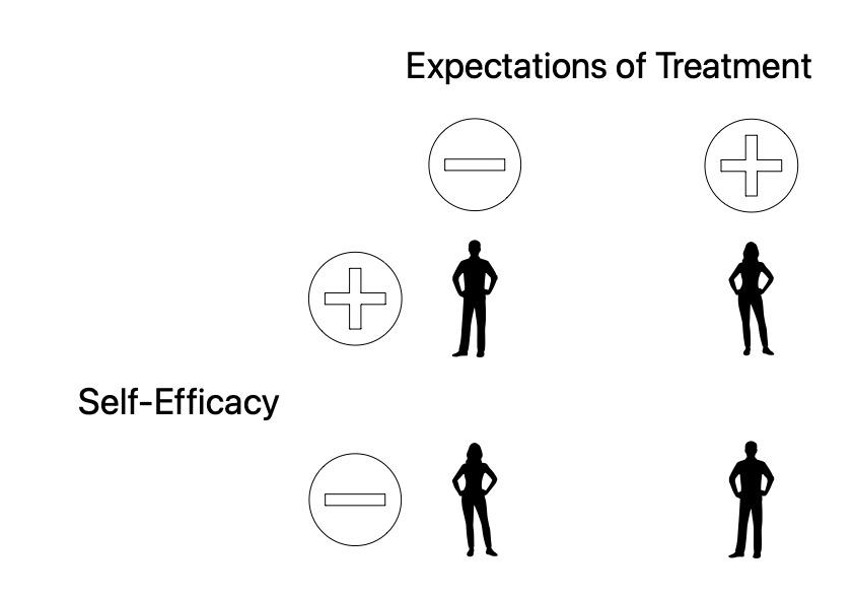

In audiology, I often think of a patient’s self-efficacy and how it might intersect with their treatment expectations. I often picture something like Figure 1 below.

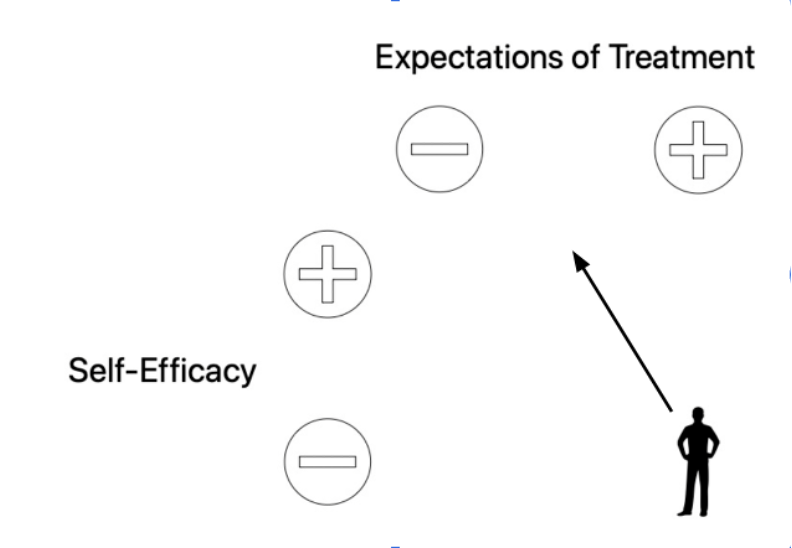

We have all interacted with each of these 4 hypothetical patients. The person to the top left has high self-efficacy and low treatment expectations. To me, this person represents the easiest to treat among the 4. They are confident in their abilities to confront and effectively manage the hearing loss and treatment journey because their expectations of care are low. This person will likely benefit more from treatment than the person to the bottom right. This individual has low self-efficacy and high expectations of treatment. This combination of psychological factors makes them more likely than not to fail with treatment. In a situation like this, it is usually wise to try to counsel them to a different location on this hypothetical 2 × 2 representation prior to fitting any amplification (see Figure 1b).

Kelly-Campbell and McMillan (2015) delved into how individuals’ belief in their ability to use hearing aids effectively influences their satisfaction and success with the devices. In this study they aimed to assess the impact of self-efficacy on patients’ experiences throughout the hearing aid fitting process. This study provides valuable insights into the role of self-efficacy in hearing aid success. It highlights the importance of addressing patients’ confidence in their ability to benefit from hearing aids.

Self-Determination Theory

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is a psychological framework that underscores the innate human tendency to pursue autonomy, competence, and relatedness in their actions and behaviors (Ryan & Deci, 2000). In healthcare decision-making, SDT suggests that individuals are more likely to engage in behaviors that align with their internal values and needs when they perceive a sense of autonomy and competence in their healthcare choices (Patrick, & Williams, 2012). Patients who feel empowered to make decisions about their treatment options and are provided with relevant information tend to exhibit greater motivation and adherence to treatment plans. Furthermore, fostering a supportive and empathetic healthcare environment that respects patients’ autonomy and encourages collaboration between healthcare providers and patients can enhance patients’ intrinsic motivation to participate actively in their healthcare decisions.

In audiology, self-determination theory (SDT) is known to intersect with a patient’s decision-making process, particularly in the context of considering getting hearing aids, in several ways:

- Autonomy: SDT emphasizes individuals’ need for autonomy in decision-making. Patients considering hearing aids may feel empowered when they can explore different options, make informed choices based on their preferences, and actively participate in decision-making.

- Competence: This aspect of SDT is comparable to self-efficacy and highlights the importance of feeling competent and capable in one’s actions. Patients may be more inclined to pursue hearing aid options if they feel confident in their ability to manage their hearing loss effectively with the support of hearing aids.

- Relatedness: SDT underscores the significance of interpersonal relationships and social support. Patients may be more motivated to seek hearing healthcare, including hearing aids, when they feel understood, supported, and encouraged by healthcare providers, family members, and peers.

Self-determination theory (SDT) also distinguishes between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, which can manifest in various scenarios, including considering getting a hearing aid:

- Intrinsic motivation (e.g., a person who wants to communicate better):

- Intrinsic motivation arises from internal factors, such as personal enjoyment, curiosity, or inherent satisfaction derived from an activity.

- Scenario: A person feels intrinsically motivated to get a hearing aid because they genuinely value the potential improvement in their ability to engage in conversations, enjoy music, or connect with loved ones on a deeper level.

- This motivation is driven by the individual’s inherent desire for personal growth, fulfillment, and well-being.

- Extrinsic motivation (e.g., a person being dragged into the clinic by family):

- Extrinsic motivation stems from external factors, such as rewards, recognition, or avoidance of punishment.

- Scenario: A person feels extrinsically motivated to get a hearing aid because they want to avoid social stigma, improve job performance, or comply with the expectations of others, such as family members or healthcare providers.

- This motivation is influenced by external incentives or consequences rather than internal desires.

Intrinsic motivation leads to more sustainable engagement and satisfaction than extrinsic motivation, as it aligns with the individual’s inherent psychological needs and values.

Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance is the discomfort experienced when an individual holds conflicting beliefs, attitudes, or values or their actions contradict their beliefs (Festinger, 1957; Tavris & Aronson, 2008). In healthcare decision-making, cognitive dissonance arises when individuals engage in behaviors that conflict with their knowledge or beliefs about health risks.

For example, in smoking cigarettes, a person may experience cognitive dissonance when they know smoking is harmful to their health but continue to smoke due to addiction or social pressures. This conflict between the knowledge of the health risks and the behavior of smoking leads to discomfort. To reduce this dissonance, individuals may rationalize their behavior by downplaying the health risks, emphasizing perceived benefits like stress relief, or avoiding information that contradicts their smoking habit. In healthcare decision-making, cognitive dissonance can influence adherence to treatment plans, preventive behaviors, or lifestyle changes.

In audiology, cognitive dissonance often manifests when individuals considering purchasing a hearing aid experience conflicting thoughts or emotions regarding their hearing loss and the need for amplification. Here are some examples:

- Denial of Hearing Loss: A person may initially deny or minimize their hearing loss to avoid the stigma of wearing hearing aids. However, this contradicts the awareness of their communication difficulties, causing cognitive dissonance.

- Cost-Benefit Analysis: Individuals may acknowledge the benefits of hearing aids in improving communication but struggle with the perceived high cost. This discrepancy between recognizing the benefits and the financial investment creates cognitive dissonance.

- Appearance Concerns: Some individuals may prioritize vanity over hearing health, hesitating to wear hearing aids due to concerns about their appearance. However, this conflicts with their desire to improve their hearing and participate fully in social interactions.

- Stigma Perception: Despite recognizing the functional benefits of hearing aids, individuals may internalize negative stereotypes or societal stigma associated with hearing loss and amplification devices. This creates a conflict between acknowledging the efficacy of hearing aids and avoiding social judgment.

Resolving a patient’s cognitive dissonance for various factors is a huge part of our job. Addressing cognitive dissonance in audiology involves education, counseling, and support to help individuals reconcile conflicting beliefs and make informed decisions about hearing aid adoption.

Therapeutic Alliance

We have discussed noise and bias in patient and healthcare professionals' interactions. We have examined the formation of narratives and how these are shaped by various psychological factors affecting both patients and audiologists. I contend that the concept of the therapeutic alliance is crucial in fostering a healthy relationship between the patient and the audiologist. The therapeutic alliance generally refers to the collaborative and trusting bond between a healthcare provider and their patient, characterized by mutual respect, agreement on treatment goals, and a shared understanding of tasks involved in achieving those goals (Rogers, 1959; Stubbe, 2018).

In audiology, this alliance is particularly important in purchasing a hearing aid. The audiologist must effectively communicate the various options, clearly explaining the benefits and potential limitations of each hearing aid type, aligning with the patient’s expectations and needs. Moreover, to successfully navigate this challenge, the audiologist must be aware of the story that a person might have unfolding in the visit and circumvent or correcting any of the various psychological constructs that influence decision-making. This cooperative approach not only assists in selecting the most appropriate device but also ensures the patient feels supported and understood throughout the process. A strong and successful therapeutic alliance leads to better compliance and satisfaction with care outcomes.

Concluding Thoughts

This paper explored the significant impact of psychological factors on audiology’s diagnostic and therapeutic processes. We highlighted the influence of confirmation bias and cognitive dissonance, which can skew clinical judgments and outcomes. Through narrative analysis, we demonstrated how patients’ and audiologists’ personal stories and experiences shape their perceptions and interactions, ultimately affecting treatment decisions and patient compliance.

A strong therapeutic alliance between the audiologist and the patient is vital. This relationship is foundational in achieving effective communication and critical in ensuring that treatment recommendations are well-received and followed. We discussed strategies for enhancing self-efficacy and motivation through informed and empathetic communication tailored to meet individual patient needs and expectations.

Key Points for Monday Morning:

- Acknowledge and actively mitigate personal biases and cognitive noise to improve accuracy and effectiveness in patient care.

- Foster a narrative-conscious approach, recognizing and integrating the patient’s and your own narrative into the clinical process.

- Prioritize the development of a therapeutic alliance, focusing on trust, mutual understanding, and agreed-upon treatment goals.

- Enhance patient self-efficacy and motivation by employing strategies that respect patient autonomy and competence, using principles from Self-Determination Theory.

- Address cognitive dissonance and confirmation bias by providing balanced information and supporting patients in reconciling conflicting beliefs or fears regarding hearing aids and treatments.

Undoubtedly, much of this information might already be familiar to most of you. Nevertheless, revisiting the factors contributing to the challenges in adopting and adhering to hearing services can be helpful. I hope this serves as a useful reminder to continue your excellent efforts and to persist in employing as many strategies as necessary to assist those we treat to feel safe, valued, and heard.

References

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Clark, K. D., Garinis, A. C., & Konrad-Martin, D. (2021). Incorporating Patient Narratives to Enhance Audiological Care and Clinical Research Outcomes. American journal of audiology, 30(3S), 916–921. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_AJA-20-00228

- Ekberg, K., Grenness, C., & Hickson, L. (2014). Addressing patients’ psychosocial concerns regarding hearing aids within audiology appointments for older adults. American journal of audiology, 23(3), 337–350. https://doi.org/10.1044/2014_AJA-14-0011

- English K. (2022). Guidance on Providing Patient-Centered Care. Seminars in hearing, 43(2), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-1748834

- Festinger, Leon (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford University Press.

- Holloway, A., & Watson, H. E. (2002). Role of self-efficacy and behaviour change. International journal of nursing practice, 8(2), 106–115. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-172x.2002.00352.x

- Jerant, A., Franks, P., & Kravitz, R. L. (2011). Associations between pain control self-efficacy, self-efficacy for communicating with physicians, and subsequent pain severity among cancer patients. Patient education and counseling, 85(2), 275–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2010.11.007

- Kahneman, D., Sibony, O., & Sunstein, C. R. (2021). Noise: A flaw in human judgment. Little, Brown Spark.

- Kelly-Campbell, R.J., & McMillan, A. (2015). The Relationship Between Hearing Aid Self-Efficacy and Hearing Aid Satisfaction. American journal of audiology, 24 4, 529-35 .

- McCormack, A., & Fortnum, H. (2013). Why do people fitted with hearing aids not wear them?. International journal of audiology, 52(5), 360–368. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2013.769066

- Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, 2(2), 175-220.

- Patrick, H., & Williams, G. C. (2012). Self-determination theory: its application to health behavior and complementarity with motivational interviewing. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity, 9, 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-9-18

- Rogers, Carl. (1959). A Theory of Therapy, Personality and Interpersonal Relationships as Developed in the Client-centered Framework. In (ed.) S. Koch, Psychology: A Study of a Science. Vol. 3: Formulations of the Person and the Social Context. New York: McGraw Hill.

- Ryan, R. M.; Deci, E. L. (2000). “Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being”. American Psychologist. 55 (1): 68–78. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68. hdl:20.500.12749/2107

- Stubbe D. E. (2018). The Therapeutic Alliance: The Fundamental Element of Psychotherapy. Focus (American Psychiatric Publishing), 16(4), 402–403. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20180022

- Tavris, C., & Aronson, E. (2008). Mistakes were made (but not by me): Why we justify foolish beliefs, bad decisions, and hurtful acts. Harcourt.