Quality and Readability of Hearing Information on the Internet

Published in Audiology Now Issue 54, Spring 2013, the magazine of Audiology Australia. Reprinted with permission.

Ariane Laplante-Lévesque and colleagues conducted the present study surveying the quality and readability of English-language internet information for adults with hearing impairment and their significant others. The study was published in a peer-reviewed journal (Laplante-Lévesque et al, 2012) and presented at conferences. The authors sincerely thank Elisabeth Ingo, Research Audiologist at Linköping University in Sweden, for her precious help in writing this summary. The study was partly funded by the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research.

Searching the Internet for Hearing Information

People with health conditions and their significant others are increasingly turning to the internet for information (Fox, 2011). When people face a health decision, the internet is their second most influential source of information after clinician advice (Couper et al, 2010). Both the literature and clinical experience suggest that people commonly search the internet for hearing information.

Quality of Internet Health Information

The quality of internet health information has been found to vary greatly (Eysenbach et al, 2002). In audiology, it is largely unknown whether the information available on the internet informs or misinforms adults with hearing impairment and their significant others. Three avenues can be considered to ensure that people benefit from internet health information:

- Clients can systematically assess the quality of the internet health information they access. However, clients rarely assess the health information they access on the internet to determine its quality (Eysenbach & Köhler, 2002).

- To address the problem that clients rarely systematically assess health information quality, web developers can adopt voluntary ethical guidelines. The Health On the Net (HON) Foundation provides one of the many voluntary website certification schemes (Boyer et al, 1998). Certifications for ethical guidelines are typically displayed on the websites and are therefore relatively easy to find.

- Instruments are available for clinicians and researchers to assess the quality of internet information. For example, clinicians can use the DISCERN, a set of 16 quality criteria to assess the quality of health information (Charnock et al, 1999). Clinicians can then share their list of good quality websites to their clients.

Readability of Internet Health Information

Literacy, or one’s ability to read and understand written information, is also highly relevant for how clients can use internet health information. A systematic review found that approximately 26% of Americans have low health literacy (Paasche-Orlow et al, 2005). Internet health information has been found to have low readability (i.e., to be written above recommended reading level; Walsh & Volsko, 2008). A text with readability above nine years of education is difficult to read and understand for many people (Walsh & Volsko, 2008).

Research Aim

To be able to guide audiology clients and their significant others who seek internet information, the quality and readability of the internet hearing information available needs to be known. The aim of this study was to evaluate the information on hearing impairment and its treatment available on the internet. More specifically, the quality and readability of English-language websites as of May 2011 was assessed.

Methods

A panel of 12 audiology experts from around the world was recruited from the authors’ professional contacts. The panel generated 38 keywords likely to be used by adults with hearing impairment and their significant others. At the time the search was conducted, Google controlled over 80% of the search engine market, and therefore Google was the only search engine used in the study. With input from Google Trends, which records keywords’ use frequency, two keyword pairs were selected from the 38 keywords for searching: hearing loss and hearing aids. The search was limited to English-language websites. The two keyword pairs, hearing loss and hearing aids, were entered in five country-specific versions of the Google search engine: Google Australia, Google Canada, Google India, Google United Kingdom, and Google United States of America.

Websites were included if they provided information regarding hearing impairment and its treatment for adults and older adults with an acquired hearing impairment and their significant others. Each website’s origin (commercial, non-profit, or government), date of last update, quality, and readability was recorded.

Quality Assessment

For each website, two measures of quality were used: the HON certification (yes/no) and the DISCERN scores (16 items rated on a scale from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicative of greater quality).

Readability Assessment

For each website, two measures of readability were used: the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Formula and the Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG). The Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Formula is similar to the Flesch Reading Ease Score (Flesch, 1948). It is based on the number of sentences and syllables per 100 words. The Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG; McLaughlin, 1969) is based on the number of polysyllabic words (words with at least three syllables).

Both measures estimate American grade level (number of years of education required to understand the text). For both measures, lower scores indicate higher readability (i.e. fewer years of education needed). Both readability tests were performed with an online tool (www.online-utility.org/english/readability_test_and_improve.jsp).

Results

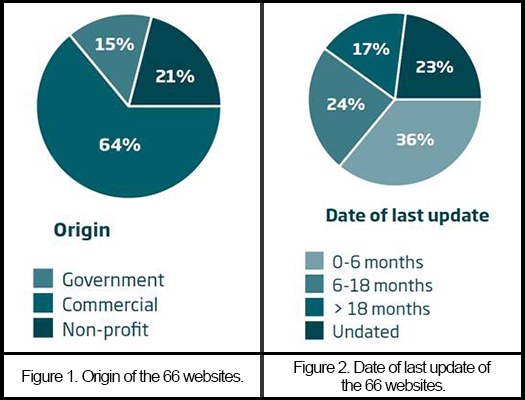

In total, 100 websites were included (2 keyword pairs; 5 country-specific versions of the search engine; 10 first websites meeting the inclusion criteria). After removing duplicates, 66 websites remained. The websites’ origin and date of last update were recorded: most of the websites were of commercial origin (see Figure 1) and had been updated within the last 18 months (see Figure 2). However, 15 of the 66 websites (23%) did not provide information about date of last update.

Quality

Only nine of the 66 websites (14%) had obtained HON certification. Over half (60%) of the websites from a government origin had HON certification. In contrast, 14% of the websites from a non-profit origin and 2% of the website from a commercial origin had HON certification. A statistical analysis showed that websites from a government origin were significantly more likely to have HON certification than websites from a commercial and from a non-profit origin.

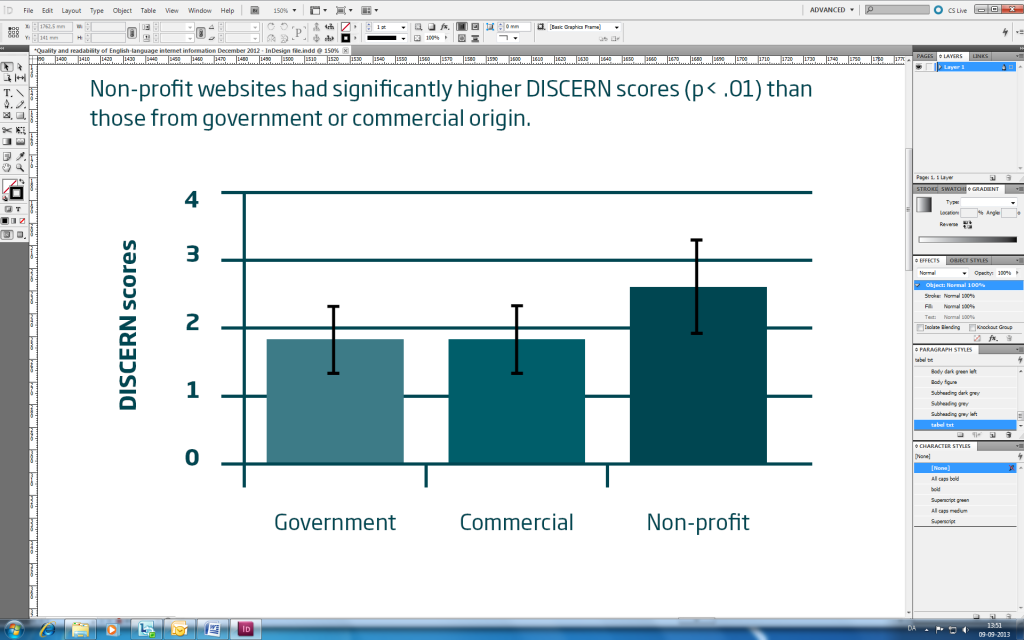

The total DISCERN scores varied from 1.1 to 3.9, with a mean of 2.0. Websites from a commercial origin had mean DISCERN scores of 1.9, websites from a government origin, 1.9, and websites from a non-profit origin, 2.6 (see Figure 3). A statistical analysis showed that websites from a non-profit origin had higher DISCERN scores (i.e. were found to have a higher quality) than those from a commercial or government origin.

Figure 3. DISCERN scores for the 66 websites, according to origin.

Readability

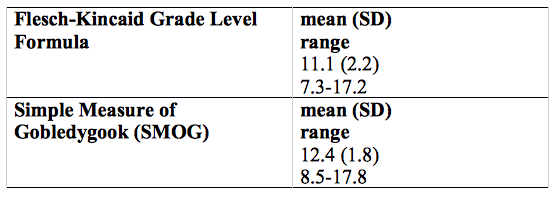

As can be seen in Table 4, the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Formula had a mean of 11.1, whilst the SMOG had a mean of 12.4. These results show that on average people required at least 11–12 years of education to read and understand the websites. Readability was not significantly associated with website origin, date of last update, or quality (HON certification or DISCERN scores). In other words, readability was independent of all other website measures this study collected.

Table 4. Mean, standard deviation (SD) and range of readability (Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Formula and Simple Measure of Gobledygook) for the 66 websites assessed.

Discussion

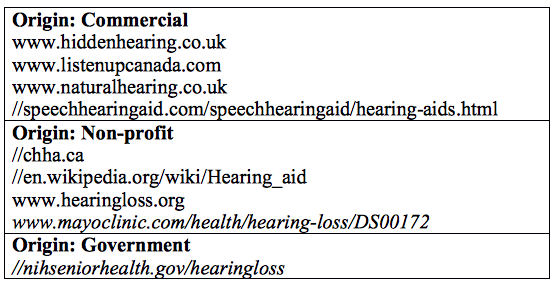

Most of the websites assessed were of commercial origin. Websites from hearing aid manufacturers and hearing aid clinics dominated. Over 60% of all 66 websites had been updated within the last 18 months, which suggests up-to-date information. Table 5 lists websites which rated high (amongst the top third) on the quality DISCERN scale and both readability measures. Audiologists can use this list as a starting point for creating their own list of recommended websites for their clients. These websites can also used as inspiration when developing websites containing hearing information.

Table 5. Highest ranked websites (top third on quality DISCERN scale and both readability measures), presented here in alphabetic order. The websites in italics also have HON certification.

It should be pointed out that this study focused on quality and readability. However, it did not assess aspects which contribute to written information accessibility other than readability. For example, design, ease of navigation, and compatibility are also important. Beyond readability, available guidelines as well as the expertise of web developers are instrumental in designing optimally accessible internet health information.

Towards Internet Health Information Quality

The HON certification and the DISCERN scale provide a good starting point for identifying high quality health information. It should be emphasised however that both HON certification and DISCERN scores ensure information coverage rather than information veracity. Nevertheless, seeking certification (e.g. HON) is a good way for website developers to ensure health information quality. Many of the websites assessed had features likely to be of great value to adults with hearing impairment and their significant others. For example, hearing impairment simulators, online hearing assessments, descriptions of the role of the different hearing health professionals, comparisons of hearing aid models and features across hearing aid manufacturers and information specifically designed for significant others can serve as inspiration for website developers. Interactive options such as recent blog posts, live chats or moderated forums are interesting information media which some websites used very successfully.

Towards Internet Health Information Readability

The readability of the websites assessed was rather low. On average, only people with at least 11–12 years of education could read and understand the internet information presented. This is higher than the recommended nine years (Walsh & Volsko, 2008). Readability measures are widely available. The online readability tool used in this study (www.onlineutility.org/english/readability_test_and_improve.jsp) provides an easy way for audiologists to determine readability before suggesting a website to their clients. The user enters a website address and the readability tool returns readability statistics for that website. Audiologists and website developers can easily assess readability and compare it to published guidelines.

Some people might assume that higher readability results in lower information quality. However, this study proves that this assumption is false. There was no association between quality and readability in the 66 websites the present study assessed. Table 5 shows that nine of the websites rated amongst the top third for quality on the DISCERN scale as well as on both readability measures. This shows how readability can be achieved without compromising quality.

Clinical Implications

This study highlights how adults with hearing impairment and their significant others might access internet health information with a range of calibre in both quality and readability. Almost half of a sample of over 6000 adults reported wishing their clinicians to be their first source of health information (Hesse et al, 2005). However, 49% of the same sample reported seeking internet health information first, with only 11% going to their clinician first. It is natural that some adults with hearing impairment and their significant others access internet health information prior to seeking professional help. They may raise the internet information they accessed during clinical encounters. Previous research shows that collaboration with the clients to analyse the information or guidance to good health information occurs in clinical encounters and leads to greater client satisfaction (Bylund et al, 2007; McMullan, 2006). For example, audiologists can assess whether the advice their clients accessed is relevant to them. Audiologists can stress any contraindications for intervention options which clients might have read about on the internet. Audiological recommendations can also be written down to guide the keywords clients might later use for internet searches. This can help individualise the internet information clients retrieve.

Audiologists guiding clients to good health information benefit from the contents of Table 5 and the previous section which provided examples of internet health information with high quality and readability. Web developers should consult these recommended websites when designing and updating websites. Audiologists wishing to embrace the internet for intervention purposes can also find inspiring examples of the clinical use of the internet with adults with hearing impairment. For example, a growing number of researchers have studied the use of the internet for hearing rehabilitation (Laplante-Lévesque et al, 2006; Thorén et al, 2011).

In summary, many of the 66 websites this study assessed had low quality and/or readability. This study provides ideas for turning the internet into a media that helps inform people with hearing impairment and their significant others.

References

Boyer C., Selby M., Scherrer J.R. & Appel R.D. 1998. The Health On the Net code of conduct for medical and health websites. Comput Biol Med, 28, 603–610.

Bylund C.L., Gueguen J.A., Sabee C.M., Imes R.S., Li Y. et al. 2007. Provider-patient dialogue about internet health information: An exploration of strategies to improve the provider-patient relationship. Patient Educ Couns, 66, 346–352.

Charnock D., Shepperd S., Needham G. & Gann R. 1999. DISCERN: An instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health, 53, 105–111.

Couper M.P., Singer E., Levin C.A., Fowler F.J. Jr., Fagerlin A. et al. 2010. Use of the internet and ratings of information sources for medical decisions: Results from the DECISIONS survey. Med Decis Making, 30 (Suppl. 5), 106–114.

Eysenbach G. & Köhler C. 2002. How do consumers search for and appraise health information on the world wide web? Qualitative study using focus groups, usability tests, and in-depth interviews. BMJ, 324, 573–577.

Eysenbach G., Powell J., Kuss O. & Sa E.-R. 2002. Empirical studies assessing the quality of health information for consumers on the world wide web: A systematic review. JAMA , 287, 2691–2700.

Flesch R. 1948. A new readability yardstick. J Appl Psychol , 32, 221–233.

Fox S. 2011. Health topics: 80% of internet users look for health information online (Pew Internet & American Life Project, February 1, 2011). Retrieved September 6, 2013 from http://www.pewinternet.org/ ∼ /media//Files/Reports/2011/PIP_HealthTopics.pdf

Hesse B.W., Nelson D.E., Kreps G.L., Croyle R.T., Arora N.K. et al. 2005. Trust and sources of health information: The impact of the internet and its implications for health care providers. Arch Intern Med, 165, 2618–2624.

Laplante-Lévesque A., Brännström K.J., Andersson G., Lunner T. 2012. Quality and readability of English-language internet information for adults with hearing impairment and their significant others. Int J Audiol, 51, 618–626.

Laplante-Lévesque A., Pichora-Fuller M.K. & Gagné J.-P. 2006. Providing an internet-based audiological counselling programme to new hearing aid users: A qualitative study. Int J Audiol, 45, 697–706.

McLaughlin G.H. 1969. SMOG grading: A new readability formula. J Reading, 12, 639–646.

McMullan M. 2006. Patients using the internet to obtain health information: How this affects the patient-health professional relationship. Patient Educ Couns, 63, 24–28.

Paasche-Orlow M.K., Parker R.M., Gazmararian J.A., Nielsen-Bohlman L.T. & Rudd R.R. 2005. The prevalence of limited health literacy. J Gen Intern Med, 20, 175–184.

Thorén E., Svensson M., Törnqvist A., Andersson G., Carlbring P. et al. 2011. Rehabilitative online education versus internet discussion group for hearing aid users: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Audiol , 22, 274–285.

Walsh T.M. & Volsko T.A. 2008. Readability assessment of internet-based consumer health information. Respir Care, 53, 1310–1315.