Parent-to-Parent Support within Family Centred Early Hearing Detection Intervention (EHDI) Programs: A Conceptual Framework

Early detection and intervention for infant and childhood hearing loss needs to be evidence-based, appropriate, timely, family- and culturally centred, and embedded within a well-integrated interdisciplinary approach to care.1–3 As noted by Moeller and colleagues, “Family centered early intervention (FCEI) is viewed as a flexible, holistic process that recognizes families’ strengths and natural skills and supports development while promoting the following: (a) joyful, playful communicative interactions and overall enjoyment of parenting roles, (b) family well-being (e.g., enjoyment of the child, stable family relations, emotional availability, optimism about the child’s future), (c) engagement (e.g., active participation in program, informed choice, decision making, advocacy for child), and (d) self-efficacy (competent and confident in parenting and promoting the child’s development.”2 While provider-to-family partnerships are considered an important principle of FCEI, connecting families to parent-to-parent and community-based support systems provides vital knowledge and experiences. Parent-to-parent support positively impacts family well-being and enables parents to effectively advocate for their child.1–3

Parent-to-parent support systems were initiated in 1971.4 They can be described as a mutual process of parents with lived experiences supporting each other. For parents raising children with disabilities, including hearing loss, parent-to-parent support yields many positive benefits and rewards. Peer-partnership encourages and supports parents in ways that are meaningful to them in their family context.5 For parents with a child or children who are deaf or hard of hearing (D/HH), parent-to-parent support has an important role in their lives.5–8

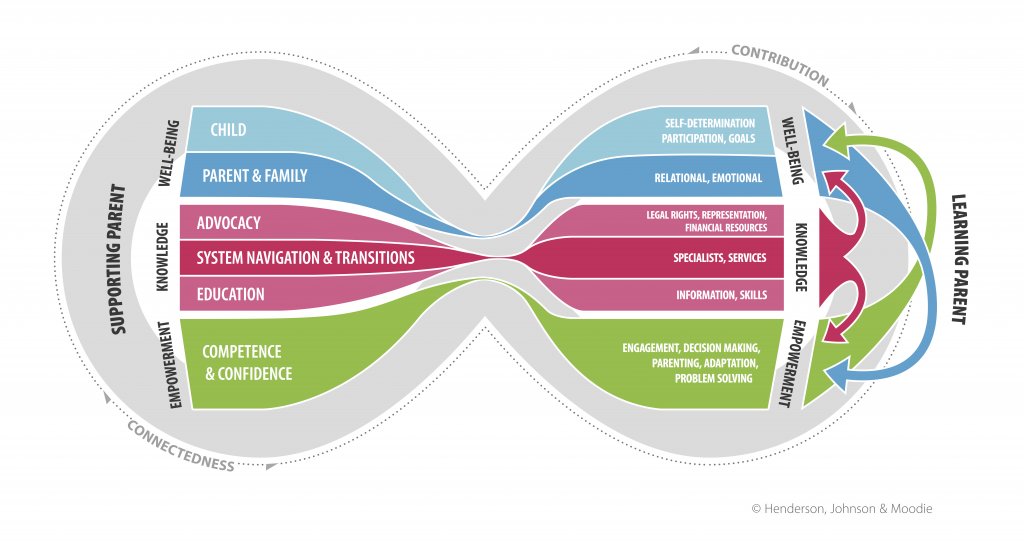

Recently, Henderson et al.5 used a scoping review methodology and eDelphi technique9 to determine the constructs and components of a conceptual framework for parent-to-parent support for parents with children who are D/HH. The interested reader is directed to the publication for a detailed description, however, we have provided the conceptual framework as Figure 1 and summarized the results in the following sections.

Figure 1. A conceptual framework of parent-to-parent support for parents with children who are deaf or hard of hearing. Additional details can be found in Henderson, Johnson &Moodie.5,9

Several important points must be emphasized before an overall description of the framework ensues. First, the “learning parent” is a parent new to or inexperienced in a situation of raising a child who is D/HH. For example, the parent(s)/family may have a child recently diagnosed as D/HH or may be experiencing a transition in the child or family's life. The “supporting parent” has the lived experience of having a child (or children) with hearing loss. Second, there is an exchange of information between the parents. This is represented in the original publications as infographics designed in the shape of a helix.5,9 Third, “connectedness” and “contribution” describe the underpinnings of the relationship. There is connectedness between the parents that facilitates a sense of belonging and affirms / validates a shared social identity often illustrated through anecdotal and life stories. There is the contribution of community relationships in their connectedness that includes, but is not limited to, D/HH role models, D/HH community and Deaf culture, peers, social groups, and family members. This community engages with the learning parent and contributes to their overall development through the sharing of ideas, information and resources. Finally, our review of the literature revealed three overarching themes (constructs)—well-being, knowledge and empowerment.5 An important relationship exists between these three constructs, namely that knowledge and well-being promote empowerment and empowerment and knowledge increase well-being.

CONSTRUCT 1(a): Child Well-Being

Child well-being is impacted by participation, self-determinations and goals. Learning parents want their family to meet with other children/families who are D/HH in their community. Child well-being is facilitated by participation in leisure and extracurricular activities, daycare/school, and ventures with family and friends. The learning parents may seek assistance from supporting parents to accrue information on participation for children who are D/HH.

The evidence indicates that learning parents may look to supporting parents to assist with access to resources or the development of their understanding of self-determination. Specifically they wish to know if there are specific actions they can take to support their child becoming self-determined. Self-determination is a “combination of attitudes, knowledge and skills that enable individuals to make choices and engage in goal-directed, self-regulated behaviour.”10 The importance of continued development of self-determination is that it assists an individual with awareness of personal preferences, and the ability to make effective choices and decisions. A self-determined child and/or family will positively impact child well-being because they are able to set goals and work toward them using strategies and supports to deal with problems.10

CONSTRUCT 1(b): Parent and Family Well-Being

Parent-to-parent support provides relational and emotional guidance to the learning and supporting parents. Five dimensions of well-being that might be explored in this relationship include: (1) material well-being; (2) health: (3) education; (4) peer and family relationships; and (5) subjective well-being.11

CONSTRUCT 2(a): Advocacy Knowledge

For many parents and families of children identified with hearing loss in infancy, the diagnosis is unexpected. These parents need to be provided with the resources and opportunities to support the positive development of their child to achieve whatever vision they have, regardless of disability and body function.12 Supporting parents who have the lived experience of childhood hearing loss can be knowledgeable about legal rights, regulations, legislation, and government policies that is important for the learning parent. The supporting parent who has already learned to advocate for financial assistance, insurance, government funding, entitlements and knows the not-for-profit or voluntary sector supplements can bring this wealth of knowledge to the relationship. In addition, it appears to be the case that supporting parents also may act as a peer advocate, parental consultant and advisor at the community, regional and national levels until the learning parents develop strengths in these advocacy skills themselves.

CONSTRUCT 2(b): System Navigation and Transition Knowledge

Friedman Narr, and Kemmery4 found that supporting parents spent much time mentoring learning parents on three primary themes: (1) hearing related conversations; (2) understanding and navigating early intervention programs; and (3) additional complexities of multiple disabilities. They helped learning parents understand assessment results, determine how to keep hearing aids on babies, encouraged them to attend follow-up appointments; directed them to appropriate specialists and helped them to develop meaningful questions for specialist appointments. Supporting parents directed them to early intervention programs and to programs and specialists that could assist in cases where hearing loss was not the only impairment. Two interesting outcomes of the parent-to-parent support literature that might not be commonly appreciated are that: (a) even when learning parents have reduced the amount of time they are in direct contact with supportive parents, they will increase the contact time during life transitions. For example, as the child moves from preschool into elementary school, or when they have ‘aged-out’ of early intervention funding programs; and (b) Parents who have been trained and are acting in the role as supporting parents will seek support from other peers at times when they and/or their child are in transition.5 This speaks to the importance, power and long-lasting strength of these peer-parent relationships.

CONSTRUCT 2(c): Education Knowledge

Parents wish to acquire information and skill. Information refers to being able to locate/receive accurate, well-balanced and comprehensive information regarding technological and research advancements, and educational, communication and assistive device options. Learning parents may feel more comfortable asking questions of other parents of children who are D/HH. The supporting parent(s) may be able to educate parents using terms that are better understood. When English is a second language, communication barriers can exist in the clinic environment. Therefore, learning parents often rely on their supporting parent who speaks the same language to educate them.4 Skills refer to skill-based instruction and support, such as sign language training/education and development of device-appropriate technological skills. These are often received as a supplement to more formal and/or specialized services and support.

CONSTRUCT 3(a): Empowerment through Confidence and Competence

Self-determination is developed throughout the life span and the components of construct 3 illustrate this. Just as the parent wishes for their child to develop self-determination, they continue the self-determination skill development journey themselves. Through parent-to-parent relationships, the confidence and competence of the learning parent is facilitated through learning to adapt and adjust to life situations. Parents develop resiliency and often stress is balanced with optimism for their family’s future. By being engaged with other parents of children who are D/HH, a parent’s ability and readiness to participate in their habilitative role is strengthened. Supporting parents help to guide learning parents to the knowledge and resources needed to cultivate ideas for decision-making, problem-solving, parenting, and supporting their child’s lifelong development.

CONCLUSION

This article describes a conceptual framework of parent-to-parent support for parents with children who are D/HH developed through a review of the literature and an international eDelphi study.5,9 The framework is grounded in the explicit and tacit knowledge of stakeholders (parents and professionals), and provides a better understanding of the important and pivotal role of parent-to-parent support in FCEI programs. This framework can be used to facilitate important policy and program development and has parent-to-parent program evaluation implications.

LIMITATIONS

The context of who gives the support, and how support is provided may be as important as what support is given. Our conceptual framework does not address important issues. Shilling et al.13 point out that although shared experience is important to successful parent-to-parent support, important organizational and processes of care must be in place. These include training, ongoing supervision and guidance/support for the supporting parents. Our eDelphi study results concur with this.9 Shilling et al.13 also point out that parent-to-parent support is person specific and it is important that we ensure we understand the characteristics of supporting parents that influence optimal outcomes as well as understand the characteristics of learning parents who desire to have and who will benefit from the parent-to-parent relationship experience.

References

- World Health Organization. Childhood hearing loss: strategies for prevention and care. Geneva: Author; 2016. Accessed from: http://www.who.int/pbd/deafness/world-hearing-day/2016/en/

- Moeller MP, Carr G, Seaver L, et al. Best practices in family-centered early intervention for children who are deaf or hard of hearing: An international consensus statement. J Deaf Studies Deaf Ed 2013;18(4):429–45. doi:10.1093/deafed/ent034.

- Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Year 2007 position statement: Principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Pediatrics 2007;120(4):898–921. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-2333.

- Friedman Narr R and Kemmery M. The nature of parent support provided by parent mentors for families with Deaf/Hard-of-Hearing children: Voices from the start. J Deaf Studies Deaf Ed 2015;20(1):67–74. doi:10.1093/deafed/enu029.

- Henderson RJ, Johnson A, and Moodie S. Parent-to-parent support for parents with children who are deaf or hard of hearing: A conceptual framework. Am J Audiol 2014;23(4):437–48. doi: 10.1044/2014_AJA-14-0029.

- Fitzpatrick E, Graham ID, Durieux-Smith A, et al. Parents’ perspectives on the impact of the early diagnosis of childhood hearing loss. Int J Audiol 2007;46(2):97–106. doi:10.1080/14992020600977770.

- Poon BT and Zaidman-Zait A. Social support for parents of deaf children: Moving toward contextualized understanding. J Deaf Studies Deaf Ed 2014;19(2):176–88. doi:10.1093/deafed/ent041.

- Shilling V, Bailey S, Logan S, and Morris C. Peer support for parents of disabled children part 1: Perceived outcomes of a one-to-one service, a qualitative study. Child: Care, Health Develop 2015;41(4):524–36, doi: 10.1111/cch.12223.

- Henderson RJ, Johnson AM, and Moodie ST. Revised conceptual framework of parent-to-parent support for parents of children who are Deaf or hard of hearing: A modified Delphi study. American Journal of Audiology (in press).

- Luckner JL and Sebald AM. Promoting self-determination of students who are Deaf or hard of hearing. Am Ann Deaf 2013; 158(3):377–86. doi: 10.1353/aad.2013.0024.

- Bradshaw J, Hoelscher P, and Richardson, D. Comparing child well-being in OECD Countries: Concepts and methods, Innocenti Working Paper, IWP-2006-03, Unicef Innocenti Research Centre, Florence, Italy; 2007.

- Simeonsson RJ. ICF-CY: A universal tool for documentation of disability. J Pol Pract Intellect Disabil 2009;6(2):70–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-1130.2009.00215.x.

- Shilling V, Bailey S, Logan S, and Morris C. Peer support for parents of disabled children part 2: how organizational and process factors influenced shared experience in a one-to-one service, a qualitative study. Child: Care, Health Develop 2015;41(4):537–46. doi: 10.1111/cch.12222.