CROS Hearing Aids Existed before CROS Hearing Aids Were Even Invented

Reprinted with permission from Audiology and ENT News (2023).

The concept of a CROS (Contralateral Routing of Sound [or Signal]) hearing aid is simple. Route the sound from the “deaf” (worse hearing) ear to the “good” (better hearing) ear. The result is that people who are deaf or hard of hearing in one ear can now better hear what people are saying from their “deaf” side.

Harry Teder of Telex Corp. patented this concept back in 1964, and the first CROS aids were fitted the following year.1 This is all well and good, but the truth is, CROS hearing aids had already been in use for 10 years by this time without anyone even realizing it! Let me explain.

With the invention of the transistor and its first use in hearing aids beginning in December, 1952, hearing aids rapidly shrank in size. This was because transistors, even the early ones, were still much smaller than the miniature vacuum tubes they replaced. In addition, eliminating vacuum tubes also eliminated the large “B” battery that these vacuum tubes required to “run.”

The result was that just 2 years after the first hearing aid containing a transistor came out – the body-worn Sonotone Model 1010 – hearing aids had shrunk so much that the electronic components could now be hidden inside the temple-pieces of eyeglasses.

However, the components were still too large to all fit into just one temple-piece, so the manufacturers put some components in each temple-piece. The four biggest components were the microphone, volume control, receiver, and battery. They put the microphone, volume control and electronics in one temple-piece and the receiver and battery in the other.

This arrangement had a big advantage. It totally eliminated feedback as the microphone and receiver were separated by 7” or 8” (18 – 20 cm) and were on the opposite sides of the head. However, by using this arrangement, the result was, in actuality, a CROS aid – the sound was picked up from one side of the head and delivered to the opposite ear.

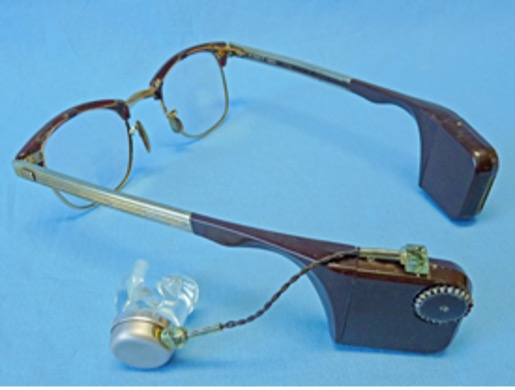

Otarion introduced the first eyeglass hearing aid using transistors, their Model L10 “Listener” (Figure 1), on December 9, 1954. It went on sale in January, 1955 and thus had the distinction of being the first CROS aid – a decade before the concept was supposedly invented.

These new eyeglass CROS hearing aids quickly became popular and by 1961 no less than 33 different hearing aid manufacturers had come out with their own versions of these CROS eyeglass hearing aids.

Interestingly enough, there were two basic styles used in these early CROS eyeglass hearing aids. The first style had large, heavy-looking temple-pieces with the electronics housed throughout their length. An example of this style was the Otarion L10 “Listener” (see Figure 1).

The second style had more or less regular-looking temple-pieces with the hearing aid electronics all housed in the temple-piece tips behind the ear. Thus from the front and side, these hearing-aid eyeglasses looked “normal” and the hearing aid part was generally invisible – buried in the hair. An example of this style was Acousticon’s first eyeglass hearing aid, their Model A-230 that came out in 1955 (Figure 2).

As you can see, instead of having the electronics spread through the length of the temple-pieces, they gathered them all into two enormous (by today’s standards) behind the ear tips of the temple-pieces (Figure 3). The microphone, electronics and volume control were housed in the right temple-piece while the battery and receiver were housed in the left one (see Figure 2).

Not to be outdone, Radioear came out with their Model 840 “Lady America” eyeglass hearing aid (Figure 3) in a similar style but with a twist. You could unplug the two parts of this hearing aid from the temple-pieces, plug them into each other and viola – you had a body or barrette hearing aid (Figure 4).

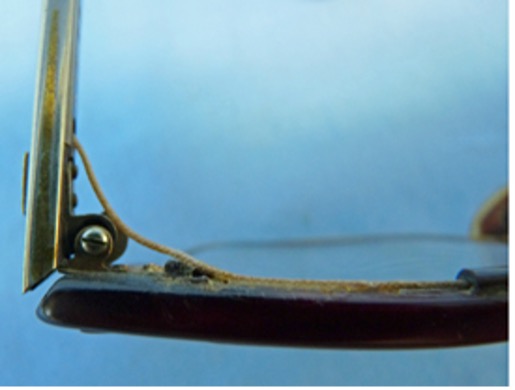

One problem the engineers had to overcome was how to send the sound signals and power from one temple-piece to the other. Their solution was to run two wires from the frame end of the temple-piece across the frame and nose bridge to the opposite temple-piece. To do this, they used one of two methods. The simplest way was to design the frames with a groove – typically across the top of the lenses and the inside of the bridge to the other side. The wires could be “loose” at the hinge (Figure 5) or more hidden. The weak point with this arrangement was that opening and closing the glasses each day could cause the wires to break at the hinge.

A more elegant solution was to make the wires in three sections – one for each temple-piece and one for the eyeglass frames. To make contact with each other at the hinge, they used an ingenious arrangement of two pins and two plates (Figure 6). When the glasses were folded, the pins and plates didn’t touch so it automatically turned the hearing aid off. When you opened the glasses to wear them, the pins touched the plates again and turned the hearing aid on.

One drawback of needing both temple-pieces is that you could not have a binaural fitting. This didn’t seem to be too much of a problem in the mid-1950s as they seldom used binaural fittings at that time. They figured that hearing in one ear was good enough.

However, it didn’t take long for components to shrink further, and by October, 1956 both Acousticon and Beltone had come out with eyeglass hearing aids that had all the components in just one temple-piece. Notice that the Acousticon Model A-235 (Figure 7) and the Beltone “Hear-N-See” (Figure 8) still had the heavy-looking temple-pieces – it’s just that all the components were contained in one temple-piece. The opposite temple-piece could be a separate hearing aid (shown in Figures 7 and 8), or it could be a matching “dummy.” Now people could wear binaural eyeglass hearing aids.

Thus, the demise of the early eyeglass CROS hearing aids began within 2 years of their first coming out. By 1958 almost all eyeglass hearing aids only used one temple-piece, although bone conduction eyeglass CROS hearing aids requiring both temple-pieces stuck around a bit longer – until 1961 or so.

So that is how CROS hearing aids existed a decade before CROS aids were invented. As Paul Harvey used to say, “Now you know the rest of the story.”

Reference

- Chasin M. Obituary: The CROS Hearing Aid (1964-2014). Hear Rev 2014;21(5).