Other People’s Ideas

Other People's Ideas

Calvin Staples, MSc, will be selecting some of the more interesting blogs from HearingHealthMatters.org which now has almost a half a million hits each month. This blog is the most well read and best respected in the hearing health care industry and Calvin will make a regular selection of some of the best entries for his column, Other People’s Ideas.

Dizziness, a topic I am definitely not an expert in. This issue of Canadian Audiologist has a focus on dizziness. At one time, I spent the better part of my day working with the dizzy patient, but like many audiologists in Canada, I drifted into hearing aids. Dizziness is a part of audiology, albeit often overlooked and could possibly represent an underserved part of the population. Alan Desmond states in his blog "ENG/VNG: Useful?" the use of the advanced ENG/VNG testing techniques are critical in properly evaluating the dizzy patient. The audiology field would probably benefit from more clinicians providing assessment and treatment options to patients who report dizziness. The increase in services would deepen the scope of practice to the general public.

In this issue of Canadian Audiologist, I have included two of Alan Desmond's blogs titled "What do you mean when you say dizzy?" There are eight blogs with the title "What do you mean when you say dizzy" and each has some form of quick clinical utility with the ability to expand your search and depth quite quickly. Alan's blogs are a wonderful 'jumping off point", to get you back into helping our dizzy patients.

ENG/VNG: Useful?

Useful, but Limited

Videonystagmography (VNG), or Electronystagmography (ENG), is the most common method of vestibular evaluation and is available in many audiology and ENT offices. A VNG or ENG examination is not a comprehensive vestibular or balance assessment, but is often described as such on clinic websites. The VNG/ENG exam is one component of a comprehensive evaluation, but many vestibular disorders and balance disorders cannot be identified through this test alone.

ENG/VNG is very important and a logical starting point for most patients with undiagnosed vertigo or imbalance. The advantages of ENG/VNG over other vestibular tests include the ability to:

1. Document nystagmus for analysis: While it is possible to visualize some types of nystagmus with the naked eye, VNG/ENG systems allow the eye to be viewed while the patient is in total darkness. One of the most useful clinical signs of nystagmus associated with an inner ear disorder is the fact that the nystagmus increase in total darkness, and decrease when the patient has the ability to focus on anything in their visual field. Bottom line, without this equipment, many patients that present with clear nystagmus when using this equipment, will not display any nystagmus when they are examined in a primary care office or emergency room for dizziness.

2. Examine cerebellar modulated voluntary eye movements: By recording eye movements and converting them into tracings, the eye speed, reaction time, direction and amplitude of eye movements can be quantified. Sensitive software measures voluntary eye movements against age matched norms, and assists in determining whether a patient has abnormal eye tracking abilities, which are suggestive of possible cerebellar disorders. Cerebellar disorders are associated with poor balance and incoordination. Abnormalities on this portion of the VNG/ENG exam suggest the need for neurological consultation.

3. Test one labyrinth at a time, which helps to localize the side of the lesion: All other vestibular function tests that involve moving or positioning the patient stimulate both ears simultaneously. The caloric portion of the VNG/ENG exam tests only one ear at a time, so an assessment can be made of the individual function or contribution of one labyrinth at a time.

4. The Dix-Hallpike exam is part of the VNG/ENG battery: By far, the most useful portion of the battery is the Dix-Hallpike exam, because it is the best test for diagnosing Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV). BPPV is the most common and easily treated cause of dizziness, yet the vast majority of patients with this condition never get the appropriate test or effective treatment.

What Do You Mean When You Say Dizzy? Part IV

Precipitating, Exacerbating, or Relieving Factors (Triggers)

Symptoms that are brought on or increased by a change in head position, or with eyes closed, suggest peripheral disease. Symptoms noticed only while standing, but never when sitting or lying, suggest vascular or orthopedic disease. Symptoms that are constant and are unaffected by position change are suggestive of central or psychiatric pathology.

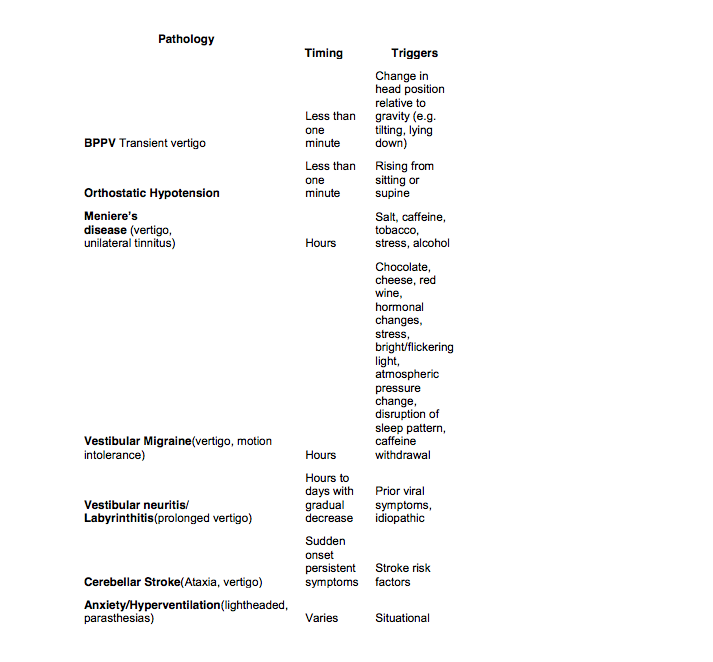

To aid in differential diagnosis in a patient complaining of vertigo or dizziness, I developed a brief guideline based on typical duration (timing) and precipitating, exacerbating factors (triggers) for the most common causes of these complaints.

What Do You Mean When You Say Dizzy? Part VIII

MOTT (MOST OF THE TIME) LIST

(General rules to aid in the dizziness diagnosis)

- A complaint of Vertigo MOTT indicates a peripheral vestibular asymmetry, but can mean Migraine or Infarct.

- A complaint of Lightheadedness, Faintness MOTT is not vestibular.

- Vertigo, of less than 1 minute duration when lying down or tilting head MOTT indicates BPPV.

- Pre-syncope and/or transient loss of balance, of less than one minute after rising MOTT indicates Orthostatic Hypotension.

- Symptoms lasting minutes to hours MOTT indicates vestibular or vascular etiology.

- Vertigo lasting hours with gradual decrease MOTT indicates unilateral vestibular pathology.

- Vertigo lasting for 48 hours or more with no improvement MOTT indicates CNS or psychiatric etiology.

- Symptoms that increase with eyes closed or with a change in head position MOTT indicates vestibular etiology.

- Symptoms noted only while standing MOTT are related to vascular or orthopedic disease.

- Associated symptoms such as unilateral tinnitus and/or hearing loss, particularly at the time of the dizziness, MOTT indicates vestibular etiology.

- Symptoms such as syncope, numbness, tingling, confusion, slurred speech MOTT indicate CNS disease.

- Nystagmus that are conjugate, diminish with visual fixation, and/or are direction fixed MOTT are of peripheral vestibular origin.

- Nystagmus that are vertical, disconjugate or direction changing without change in head position are MOTT due to CNS disease.

- Nystagmus that increase when gaze is directed toward the fast phase, and decrease when gaze is directed toward the slow phase are MOTT a sign of acute peripheral vestibular asymmetry.

The Role of Audiometry in Vestibular Testing

“Why are you doing a hearing test? My hearing is just fine.”

I’ve heard this frequently enough over the years that I know to take a minute to explain to every vestibular patient, before we get started, why we require an audiogram. I keep it pretty straightforward and simple:

“We do a quick hearing test on every patient complaining of dizziness because we have to be sure there is no infection or inflammation behind your eardrum, and we need to make sure there isn’t any unexplained difference in hearing between the two ears. Some inner ear problems affect hearing as well. Some do not. Knowing your hearing levels will help us rule out some causes.”

Audiometric evaluation is a necessary starting point for a number of reasons, but it primarily provides information about auditory asymmetry, possible retrocochlear pathologies, and the health and integrity of the ear canal and tympanic membrane before caloric irrigation.

Audiometric evaluation consists of pure-tone air and bone-conduction thresholds; speech audiometry, including speech reception threshold (SRT) and speech recognition tests; tympanometry; acoustic reflex threshold and decay tests; speech rollover tests; and, when indicated, otoacoustic emissions (OAEs)

Auditory Symmetry

Auditory asymmetry refers to a significant difference in threshold hearing levels between the ears and indicates the possibility of peripheral vestibular or auditory nerve pathology. The Mayo Clinic1 uses a criterion of a ‘‘difference of 15 dB or greater averaged across 500, 1000, 2000, 3000 Hz or differences of 15 dB or greater in speech recognition thresholds’’ to determine significant asymmetry.

Although there are numerous causes for asymmetric auditory sensitivity, including middle ear pathologies, various patterns have been linked with specific vestibular disease. Endolymphatic hydrops (Meniere’s disease) is frequently accompanied by unilateral, fluctuating, low-frequency sensorineural hearing loss. Acoustic neuroma is often characterized by an asymmetry in the higher frequencies. Perilymph fistula and labyrinthitis are usually accompanied by unilateral sensorineural hearing loss with no specific pattern or configuration of loss.

Retrocochlear Pathology

Retrocochlear pathology refers to site of lesion at the cranial nerve (CN) VIII, cerebellopontine angle, or root entry zone of the CN VIII into the brain stem. A number of audiometric findings are suggestive of retrocochlear site of lesion and may be found in acoustic neuroma, multiple sclerosis, and a variety of brain stem lesions. Audiometric signs consistent with possible retrocochlear pathology include the following:

- Asymmetric, typically high-frequency, sensorineural hearing loss

- Speech recognition scores poorer than would be expected based on audiometric configuration and severity

- Rollover (decreased speech recognition scores with higher intensity speech presentation levels)

- Absent or elevated acoustic reflex thresholds or abnormal acoustic reflex decay

The Ear Canal and Tympanic Membrane

The health and integrity of the ear canal and tympanic membrane must be ascertained before beginning vestibular evaluation. Many patients with middle ear pathology will complain of dizziness as well as other auditory symptoms. It is prudent to treat the middle ear problem first to determine whether there is an improvement in the complaint of ‘‘dizziness.’’ Also, treatment might remove confounding factors affecting sensitive evaluation, such as aural fullness, tinnitus, and otalgia, which are common to both middle ear and peripheral vestibular disorders. Conditions such as tympanic membrane perforation, cerumen impaction, external otitis, or discharge may contraindicate caloric irrigation of the external auditory canal.

Footnotes

- Robinette, Bauch, Olsen, & Cevette, (2000). Auditory brainstem response and magnetic resonance imaging for acoustic neuromas. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 126(8), 963–966.↵

BPPV-Stat Sheet

This week, we are going to take a quick look at some (at least to me) startling and depressing statistics related to Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo. Each will be linked to the abstract if you want further detail. I will be exploring current management of BPPV over the next few weeks.

1. Two recent studies explored the time period from initial presentation of symptoms of BPPV to correct diagnosis. Fife and Fitzgerald report that in the United Kingdom, the mean wait time from initial presentation to correct diagnosis was 92 weeks. A more recent study out of China found the delay to be longer than 70 months.

2. In both studies mentioned above, the subjects were treated with Canalith repositioning (CRP) once the diagnosis of BPPV was made. In the Chinese study over 80% were successfully treated with one CRP, while the Fife and Fitzgerald study reports 85% were successfully treated.

[Editors note: I don’t know about you, but this blows my mind. This indicates that the average person with BPPV goes years before they are diagnosed correctly, then over 80% are successfully treated on the day they are diagnosed. We know BPPV is common. It is easy and inexpensive to diagnose and treat, yet the inefficiencies of the health care systems seem determined to ignore this. Is it any better in the United States?]

3. Katsarkis (1994) reported that more than one third of 1194 patients seen for the complaint of “dizziness” were found to have “confirmed or strongly suspected” benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

4. Oghali (2000) reports that 9% of the general geriatric population has BPPV at any given time

5. Despite the high incidence of BPPV, testing for positional vertigo is still rare (<10%) in the primary care setting (Polensek, 2008)

[Editors note: All three of these studies are from the United States. We will continue with this stat sheet next week, and explore treatment options]