Using Bluetooth (And Personal Hearing Aids) for Live Music Performance

A common question from performing musicians who wear hearing aids with Bluetooth wireless transmission enabled is whether they can use their personal amplification as in-ear monitors. This would involve connecting the output of the audio rack to a Bluetooth accessory such as a TV listening device which would route the sound wirelessly to their own hearing aids and personal amplification settings.

An advantage of this approach is two-fold: the output in their ear canals would be controlled and have been verified to be at an optimal level, and the level-dependent equalization/compression characteristics of their hearing aids can be used to ensure that soft sounds remain soft but audible, and loud sounds remain loud but do not exceed their tolerance levels. In contrast, using commercially available in-ear monitors would not be optimized for the musicians’ hearing loss and would not provide different amounts of gain for differing input levels.

First suggested by Lesimple (2020), this technique has been recommended with varying levels of success with performing artists over the past several years. One of the issues is that, unlike the highly controlled TV output, the audio rack output in a performance venue can be variable. If this is the only problem, an inexpensive pre-amp (with its own volume control) can be placed between the output of the audio rack and the input to the Bluetooth emitter accessory. Of course, the Bluetooth emitter accessory (such as a TV listening device) needs to have an input jack, and unfortunately, for some manufacturers, this is not always the case.

And Bluetooth is not without its limitations. Any wireless transmission has a distance limitation (currently 10 meters) but also uses a 2.4 GHz transmission architecture. Although this wavelength is appreciably shorter than previous incarnations of wireless transmission that used longer wavelength frequencies in the MHz range (such that no intermediary device is currently required), a disadvantage is that 2.4 GHz is near the resonant frequency of body fat. This is why microwaves also use 2.4 GHz. This issue may arise when someone walks between the emitter (or TV listening device) and the musician, thereby temporarily cutting out the Bluetooth signal. Therefore, the emitter must be kept as close as possible to the user. Typically, that means the unit being on stage or very close to it.

But It Is Not Always Just a Simple “Pre-Amp” Issue – Sometimes A “Balancing” Act Is Required

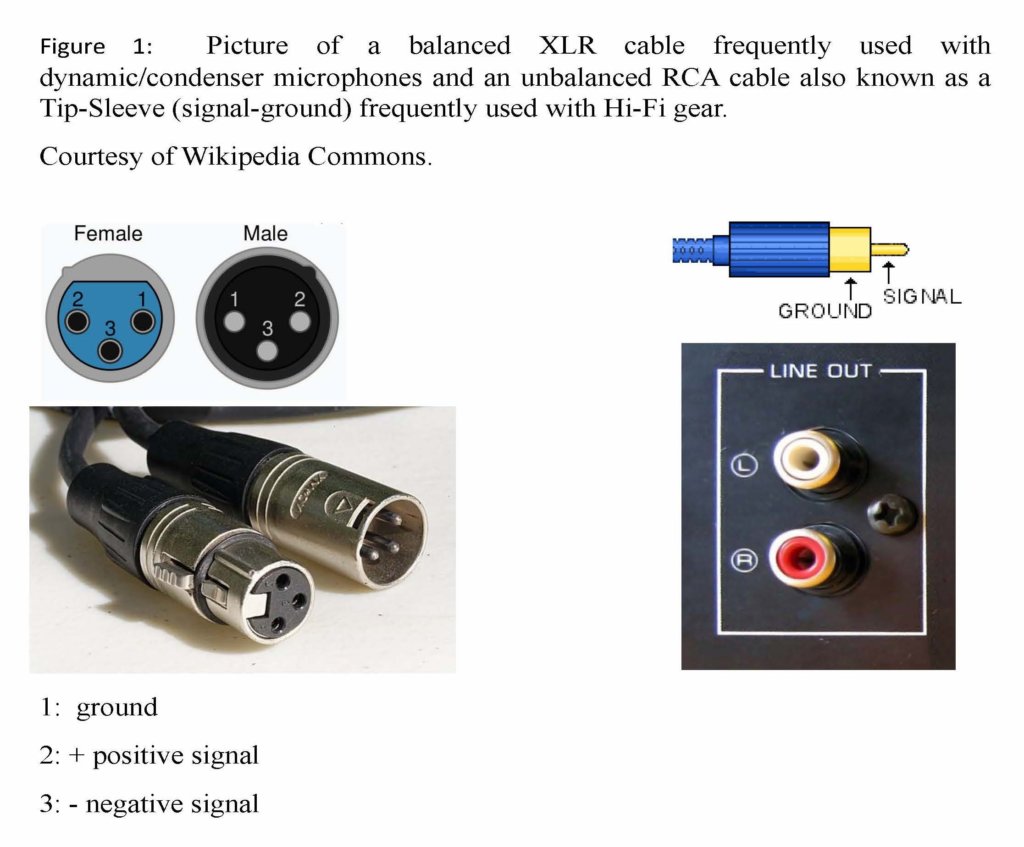

Interfacing the two systems (pro audio gear and the “TV” Bluetooth accessory emitter) requires a little bit of a “balancing” act. In the pro audio world, virtually everything uses what is known as balanced lines to interconnect gear. This is a tried-and-true method to run long lines without signal degradation or pickup of RF or electromagnetic interference along the way. Audiologists typically learn about balanced and unbalanced lines only when learning the basics of microphones.

We are presented with a scenario where we have to interconnect a “balanced” (also known as Lo-Z or low impedance) output from the monitor output of a mixing console to the “unbalanced” input of the TV Bluetooth accessory device. At home, where these devices were intended to be used, the connection is simply an “unbalanced” connection facilitated by an “RCA” cable connector or a simple 3.5 mm headphone jack. But in music venues, we have a mixing console that may be located anywhere from the wings of the stage to the centre or rear of the theatre. And most pro mixing consoles do not have any unbalanced connections, for good reason. Some smaller mixers may have an unbalanced input/output, but normally cannot access the monitor mix channels you need for a personal monitor mix.

We are left with trying to figure out a way to connect the balanced output of the audio rack with the input to the Bluetooth hearing aid accessory. Some folks may try to connect them by cobbling together a few adapter jacks or cables, but even with a pre-amp, that can be a recipe for a degraded signal reaching the performer wearing hearing aids.

The Better Way

The proper way is to use a transformer-isolating device to give us a balanced signal from an unbalanced source correctly. Quite common in the music industry, these are colloquially known as “DI” – Direct Inject devices. These are typically used to connect unbalanced outputs (Hi-Z or high impedance) from guitars and similar instruments with pickups to the mixing console’s balanced inputs. The most common of these devices are “passive” needing no external power supply to operate - they simply have a basic isolating transformer inside that converts the signal from unbalanced to balanced using a 1/4” jack on the instrument side and the ubiquitous 3-pin XLR connector on the console side. The XLR cable is the one that is typically seen being used with professional microphones. Any working musician has undoubtedly seen or used these DI’s… or tripped over them on stage at any number of their gigs.

But Wait a Minute

We want a method to “convert” a balanced system to the unbalanced Bluetooth accessory system - not the other way around like just described… we need a way to take a balanced OUTPUT (from a mixing console) to an unbalanced INPUT on our Bluetooth accessory/hearing device! However, the beauty of a passive DI is that they work in both directions. (This is not true in “active” or powered ones.)

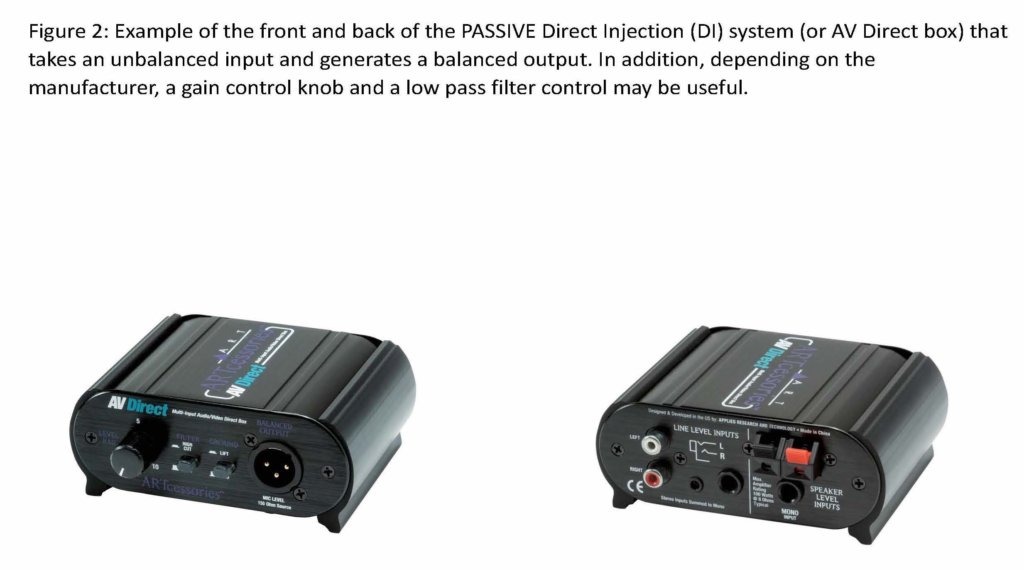

Figure 2 shows an AV-Direct box (ART manufacturer). At first glance, this looks like it has an RCA (unbalanced) INPUT to an XLR (balanced) OUTPUT which is the opposite of what we need. We required a method to convert a balanced OUTPUT from the console to the unbalanced INPUT of the Bluetooth accessory. And the connectors used - specifically the male XLR - reflect this standard of usage for this DI. We will turn this around… because a passive DI can work in both directions.

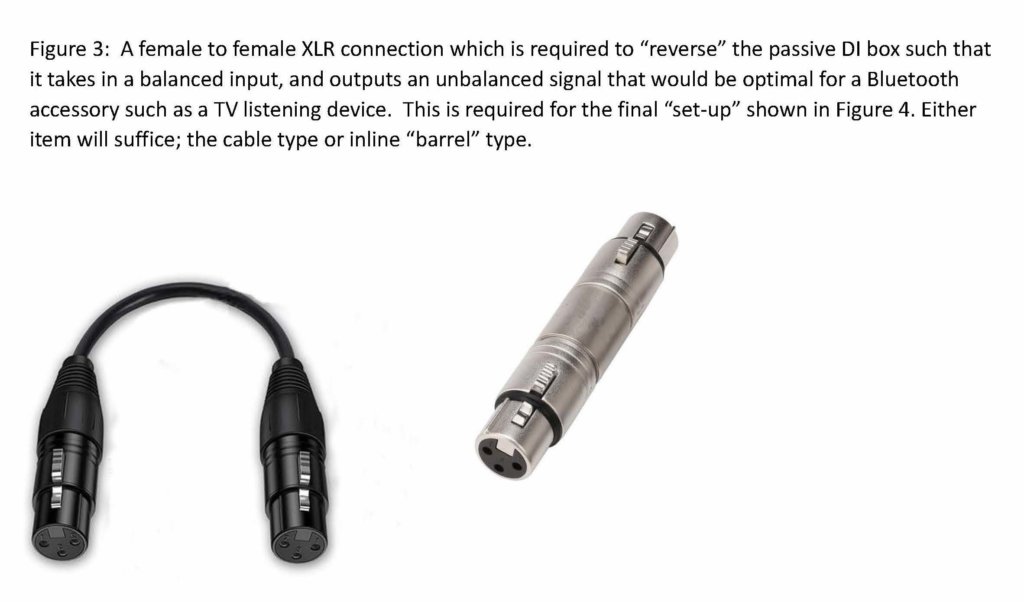

A Female-to-Female Adaptor to the Rescue

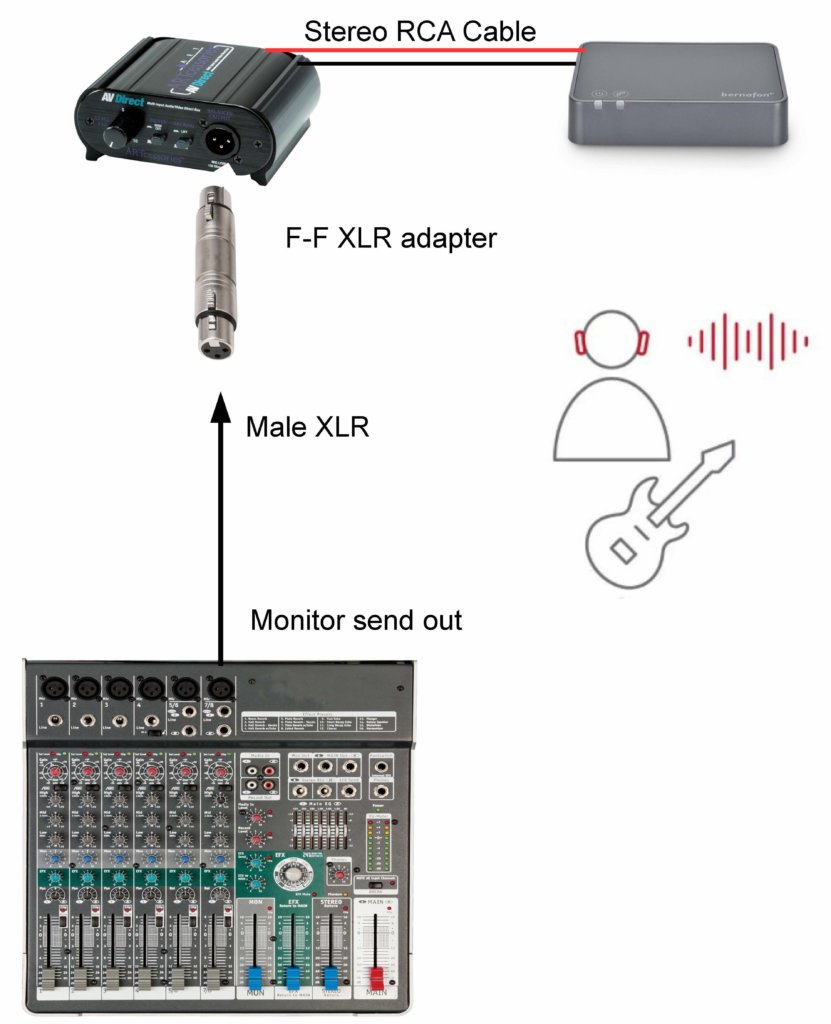

A simple “turnaround” (female-to-female) XLR cable (or inline F-F XLR barrel connector) allows us to inject the console monitor send (Male) XLR into what is labeled as an output on the AVDirect box. It gives us the unbalanced stereo (… well, actually summed mono) output on the RCA connectors on the AVDirect.

Then we can connect the red and white RCA cables from the AVDirect to our Bluetooth accessory input. Have a sound engineer (or you) start sending a personal monitor mix down your mix output channel on the console just like they do for any In-Ear-Monitor system (IEM) or stage (speaker) wedges for the other musicians. Now you have the console monitor mix firing straight to your Bluetooth device and you can control the input to your patient’s personal hearing aids via your smartphone.

Other brand DIs would achieve the same function. However, the ART “AVDirect” also has a volume knob, for further adjustments and there is also a switchable low pass filter @ 4.8 kHz that can be engaged for the Bluetooth accessory. In this scenario, there have been suggestions from audio engineers to filter out audio above 6 kHz, for improved results, so this switch easily provides this function. Your results may vary. Also, many other DIs only have a 1/4” input jack; this one has both 1/4”, 3.5 mm, and, more to our liking, the RCA jacks that the Bluetooth accessory requires. This DI has a very cost-effective street price of only $70.00.

Armed with this cookbook-type knowledge, and for under $100.00, you should have better results interfacing a hearing device into the pro audio rack setup.

Note: Parts of this article were also published in the March issue of HearingReview.com

Reference

- Lesimple, C. (2020). Turn your hearing aids into in-ear monitors for musicians. https://www.bernafon.com/professionals/blog/2020/ hearing-aids-as-in-ear-monitors